One of the most venerated deities in the Egyptian pantheon, Hathor was a mother goddess who was often depicted with cow horns and a sun disc.

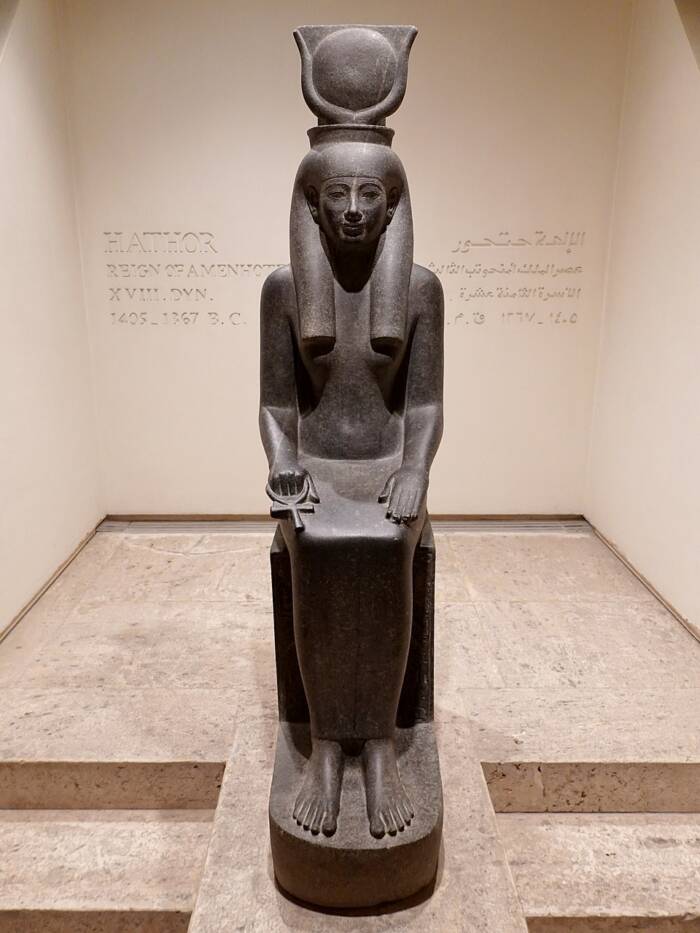

Avrand6/Wikimedia CommonsA statue of Hathor at the British Museum.

Thousands of years ago, ancient Egyptians began worshipping Hathor, a powerful goddess associated with love, fertility, and motherhood.

Often depicted with a cow’s head or as a woman adorned with cow horns, Hathor’s symbolism is deeply rooted in her maternal and nurturing qualities. Her association with fertility and the sun, and her ability to offer protection and compassion, made her one of Egypt’s most beloved goddesses.

Worshipped across the region, Hathor wasn’t just a divine protector — her rituals and festivals reflected her central role in the everyday lives of Egyptians. During births, marriages, deaths, and other profound moments of life, Hathor’s influence was sought by all social classes, from sailors seeking her protection on the Nile to pharaohs who wanted to legitimize their rule.

With more temples than any other ancient Egyptian goddess, Hathor stands as one of the most powerful deities in Egyptian mythology.

The Origin Story Of Hathor, Goddess Of Love And Fertility

Public Domain Bovines at the top of the 31st century B.C.E. Narmer Palette are believed to be an early reference to Hathor.

In Egypt of the 31st century B.C.E., artists frequently focused on images of cows or women with horn-like arms. This was part of a larger, ancient trend which viewed cows as a representation of feminine and maternal energy, due to their ability to produce milk. Cow motifs appeared in some of ancient Egypt’s most influential art pieces, including the 31st century Narmer Palette, and it’s from this imagery that the goddess Hathor likely emerged.

Though no specific reference to Hathor was made until the “golden age” of Egypt’s Old Kingdom (c. 2613 – 2494 B.C.E.), the goddess rapidly grew in prominence. She became associated with the sun god Ra — sometimes as his wife, sometimes as his daughter — and absorbed the cult of other older, popular, cow-like deities like Bat.

Hathor was often depicted as a human woman with a large headdress made of two cow horns and a sun disk. However, other depictions show Hathor as a white cow or a human woman with a cow head. Additionally, she sometimes appears as a sycamore tree, lioness, or cobra.

The goddess’ cult was located in the city of Dendera, 42 miles north of Luxor. Though she was worshiped throughout Egypt, her most popular temple was located in Dendera, and both men and women served as clergy.

Olaf Tausch/Wikimedia CommonsA statue of Hathor at the Luxor Museum.

Hathor thus stood at the center of Egypt’s spiritual heart, and legends of her lineage, likeness, and powers were put to papyrus and carved in stone.

The Mythology Of Egypt’s Motherly Goddess

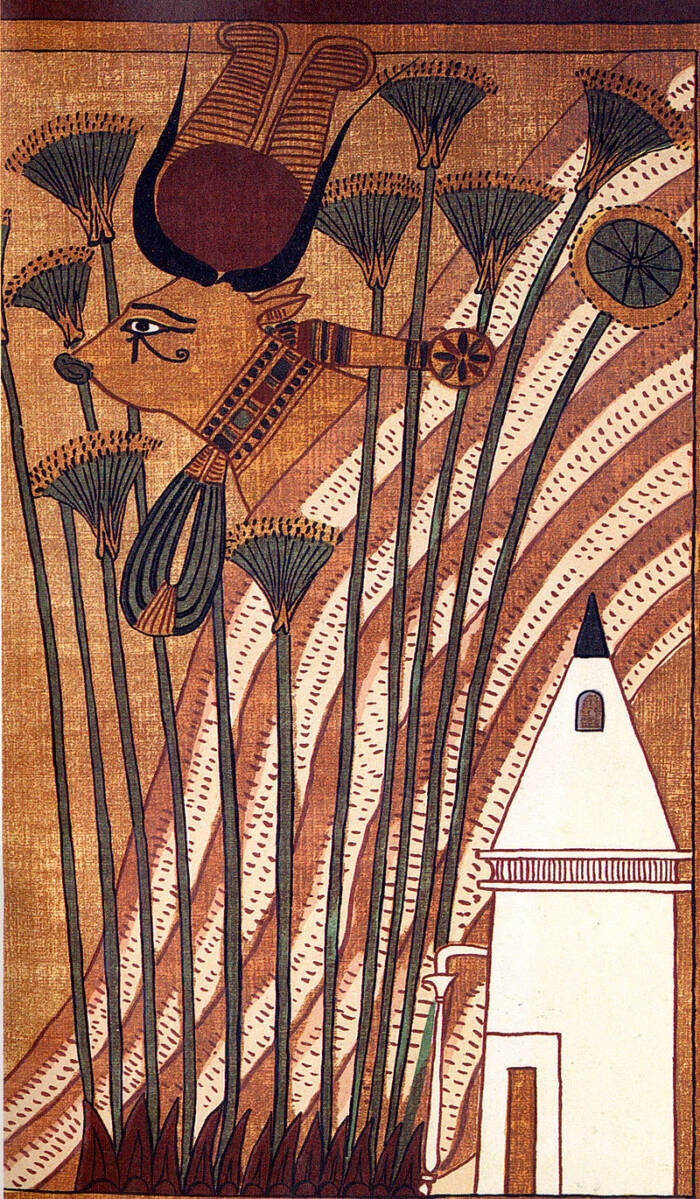

Public Domain Hathor as a bovine in the Book of the Dead c. 13th century B.C.E.

Because of Hathor’s widespread influence across Egypt, the goddess has taken on several forms that make her less like a single, easily defined deity and instead a collection of ideas about the Egyptian view of femininity.

Often called “mistress of the sky,” Hathor is seen as a maternal figure in the Egyptian pantheon. According to Egyptian texts, she was initially seen as the mother of Horus, the god of sky. (Indeed, Hathor’s name translates to “House of Horus” or “Domain of Horus.”) In one myth, she nurses Horus after he is wounded by Set, the god of storms. (This maternal imagery often appears in Egyptian art, especially in the “divine family” motif, which shows two adult deities with their infant child.)

But Hathor also has a strong connection to the sun, which is why she was known as the “Golden One.” She was linked to the sun god Ra, either as his wife or daughter, and was seen as Ra’s “Eye.” Indeed, in the 14th-century B.C.E. Book of the Heavenly Cow, Ra sends Hathor to squash a human rebellion. In taking a more vengeful form, Hathor becomes Sekhmet, the goddess of war and healing, before Ra turns her back into Hathor.

Hathor and Sekhmet are thus often interpreted by historians as a reflection of the ancient Egyptians’ view of women, who were thought to possess both gentle and violent qualities.

Panegyrics of Granovetter/Wikimedia CommonsA temple for Hathor in Dendera, the heart of her cult.

Undoubtedly, Hathor is best remembered as the goddess of love, fertility, and motherhood. Various myths portray her as a creator of the universe alongside male deities, emphasizing her profound beauty and divine power. While Ra was her most famous consort, Hathor was believed to have had romantic and sexual relationships with many deities, including Amun, Horus, and Montu. Hathor is even known as the “Lady of the Vulva” and the “Hand of God,” which is seemingly a nod to masturbation.

In one tale from Egypt’s New Kingdom period (1550–1070 B.C.E.), “The Contendings of Horus and Set,” Ra, falls into a depression after an insult from another god. However, he is cheered up by Hathor, who exposes her naked body to him to encourage him back to his duties.

Though the cow was her most iconic symbol, Hathor was also associated with sycamore trees, which were linked to her due to their milk-like sap. Beyond motherhood, Hathor’s role in the cycle of fate was significant, as she governed birth and the beginning of life. For this reason, she was also revered in the afterlife.

In the Book of the Dead, Hathor is depicted in her bovine form, guiding the deceased into a warm and comforting afterlife, reinforcing her status as one of the most important and nurturing deities in the Egyptian pantheon.

How Was The Mistress Of The Sky Worshipped?

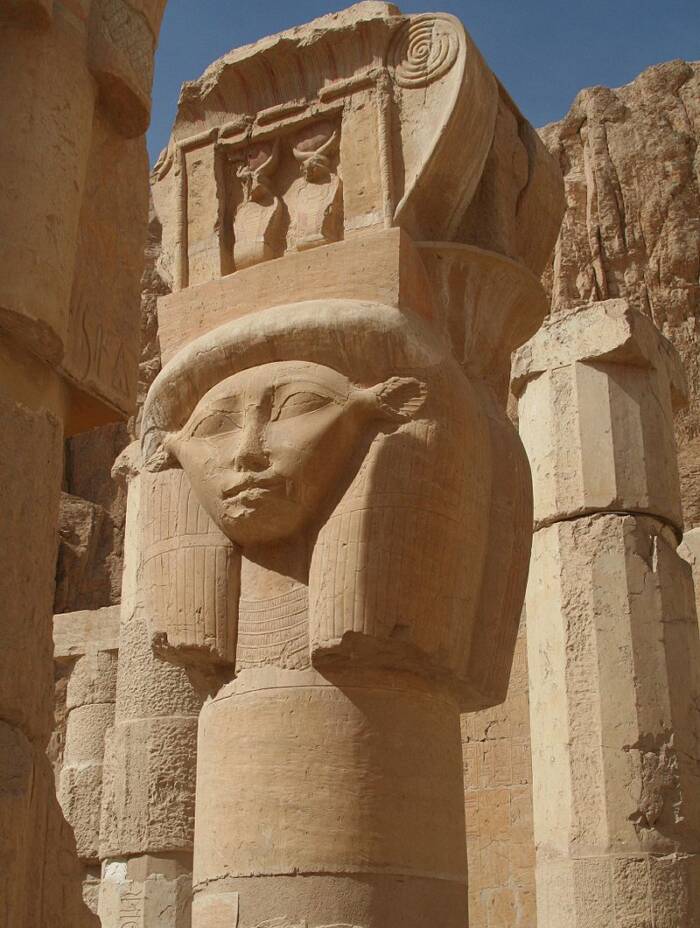

Public DomainA depiction of Hathor at the Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut, c. 15th century B.C.E.

As the goddess of motherhood and fertility, Hathor was an especially important deity among ancient Egyptian women. Indeed, out of all the female goddesses in the Egyptian pantheon, Hathor had the most temples dedicated to her, with places of worship established in Memphis, Deir al-Bahar, and especially Dendera, the heart of Hathor’s cult.

The Temple of Hathor in Dendera has origins dating back to the Old Kingdom, with renovations occurring as recently as the first century B.C.E. The temple is one of the best preserved in all of ancient Egypt and features elaborate halls, shrines, and crypts.

Among the royal class, the goddess was a useful tool to legitimize their power. In many depictions, the motherly goddess nurses pharaohs and appears alongside them as their wife. Even female members of the ruling class wanted themselves depicted with the icons and symbols of Hathor, most likely to emphasize their feminine strength.

One female pharaoh from the New Kingdom period, Hatshepsut, used her power to build temples in honor of Hathor and was even buried at a site known for its worship of the goddess.

Elias Rovielo/Flickr Columns with Hathor’s face on them at the Temple of Hathor in Dendera, Egypt.

Outside of the aristocracy, Egyptians could worship Hathor during the Festival of Drunkenness, an annual festival meant to celebrate her return to herself after transforming into the violent Sekhmet. Participants would drink, dance, ornament themselves with makeup, and sing until they reached a state of religious fervor — a time when they could connect with the gods.

The festivities would have included “lighting torches, men playing drums, and women playing double-headed flutes and rattles,” Solange Ashby, a scholar of ancient Egyptian language and Nubian religion, told The Getty Center. “The women would be singing and clapping; some young women can be seen dancing scantily clad doing backbends, adorned with jewelry.”

Other festivals and events in Hathor’s honor frequently occurred during the third month of the Egyptian calendar, named after the goddess.

In private, worshippers would dedicate shrines in honor of Hathor, especially if they were women of childbearing age. Besides praying for protection in childbirth or guidance in romances, both men and women looked to the goddess for her power in deciding fate, guiding people to the afterlife, and providing abundance. As such, various artifacts, including sculptures of women giving birth, have been discovered across Egypt.

These multifaceted roles made Hathor one of the most influential deities in the Egyptian pantheon. Maternal, gentle, but capable of great rage, Hathor oversaw some of the most important spheres of human life. Ancient Egyptians looked to her guidance when it came to the world of love and fertility and, to ensure her favor, built temples to her across their kingdom.

After reading about Hathor, discover the story of Anubis, the ancient Egyptian god of death. Or, learn about Nefertiti, the powerful queen of ancient Egypt.