Despite his heroic actions in World War I, U.S. Army soldier Henry Johnson didn't receive his due until 2015 — 86 years after he died in obscurity and poverty.

Although African Americans had been serving in the U.S. Armed Forces since the Revolutionary War, they still faced discrimination and segregation within the military for centuries. Until President Harry Truman integrated the military in 1948, soldiers of color had to serve in “all-Black” units. One of those soldiers was a man named Henry Johnson.

A brave private who served during World War I, Johnson was one of thousands of Black Americans who rushed to enlist during the “war to end all wars.” Though segregation was still in full force in both civilian and military life when the U.S. entered the war in 1917, many Black soldiers still wanted to serve their country. They also believed that proving themselves on the battlefields of Europe would show they deserved equal rights back home.

But despite the fervent enthusiasm of the Black soldiers, most American military commanders had little faith in their combat abilities.

All-Black units were often relegated to menial labor off the front lines, such as transporting supplies or digging latrines. They were rarely given sufficient training. Toward the end of the war, however, one all-Black regiment — which included Johnson — would gain fame as a legendary combat unit.

Henry Johnson And The Harlem Hellfighters

U.S. ArmyPrivate Henry Johnson of the Harlem Hellfighters.

Like many other all-Black regiments during World War I, the 369th Infantry Regiment was originally stuck with menial tasks. But by the time the U.S. entered the war, France was becoming desperately short on troops.

As a result, the U.S. Army lent the 369th Infantry Regiment to their ally. Worn down by years of brutal combat and lacking the same prejudice against Black people as the Americans, the French Army eagerly welcomed the new troops, who soon became known as the Harlem Hellfighters since so many of the soldiers hailed from the Harlem neighborhood in Manhattan.

Despite their lack of training, the troops were outfitted with French weapons and helmets and sent straight to the front lines near the Argonne Forest.

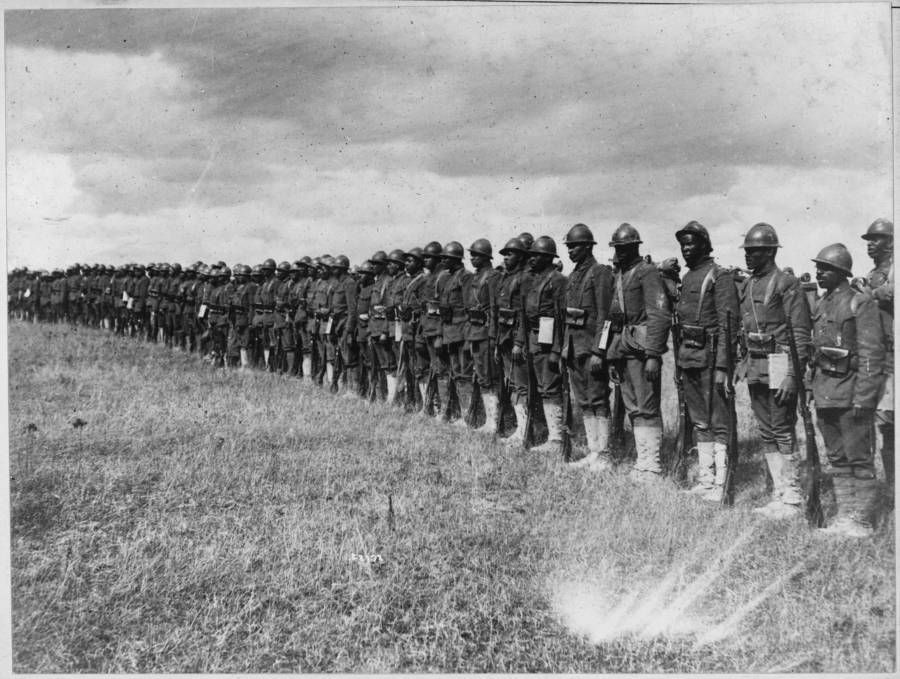

Wikimedia CommonsThe Harlem Hellfighters, pictured in 1919.

One of the Hellfighters sent out into this trial-by-fire was 26-year-old Private Henry Johnson, who had worked as a railroad porter prior to enlisting in the Army. Johnson, who lived in Albany and not Harlem (and was actually born in Winston Salem, North Carolina), personally thought it was “crazy” to send untrained soldiers right into battle.

But he was more than eager to prove himself, telling his superior that he would “tackle the job.”

Johnson and another Hellfighter, Needham Roberts, were on sentry duty one night in 1918 when all of a sudden they heard an ominous “snippin’ and clippin'” in the darkness near the fence that the French had set up as a perimeter. Recognizing the noise as wire-cutters, Johnson lobbed a grenade in the direction of the sounds, which caused the Germans to open fire.

Roberts was soon hit by a grenade and could do little more than lie in a trench and hand ammunition to Johnson as he fought back against the Germans. When the Americans exhausted their supply of grenades, Johnson began to return fire with his own rifle, but accidentally jammed it when he tried to put an American cartridge in the French weapon.

Library of CongressNeedham Roberts, who fought alongside Henry Johnson as a Harlem Hellfighter.

Henry Johnson refused to give up the fight just because he had run out of ammunition and was now completely surrounded by a far-superior force. The under-trained private began clubbing Germans with the butt of his rifle until it splintered. When Johnson saw that the enemy was attempting to take Roberts prisoner, he charged them with his bolo knife and held them off until reinforcements finally arrived to help the Americans out.

Johnson and Roberts held the Germans off on their own for an hour. They never abandoned their post and successfully prevented the Germans from breaking through the French line. Johnson had sustained over 21 wounds, but he ended up killing four Germans and wounding up to 20 more.

“There wasn’t anything so fine about it, just fought for my life,” said Johnson. “A rabbit would have done that.”

The French, however, disagreed and awarded him and Roberts the Croix de Guerre — the country’s highest military honor. The two Hellfighters were the first American privates to receive the honor and the entire French force where they were stationed lined up to watch the ceremony.

The Hellfighters’ Return To The United States

Wikimedia CommonsThe Harlem Hellfighters in France.

Back home, however, Henry Johnson’s valor was not officially recognized.

Despite being dubbed by former president Theodore Roosevelt as one of the “five bravest Americans” to serve in the entire war and having his photo plastered all over stamps and Army posters, Johnson did not even receive disability pay — something he desperately needed due to his many injuries.

And when Johnson and the rest of the Harlem Hellfighters returned home to New York in 1919, they were forced to march in their own victory parade down Fifth Avenue in Manhattan, since they were not allowed to join the “official” victory parade and march next to the white soldiers.

New York National GuardHenry Johnson in the Harlem Hellfighters’ 1919 victory parade.

This did not stop thousands of people from lining the streets to cheer on the returning troops, in particular Henry Johnson — now known as “Black Death” for his skills in battle — who led the procession in an open-top car.

Johnson returned to his job on the railroad after being discharged, but found it difficult to work because of his war wounds. Tragically, he died in 1929, at the age of just 32 of myocarditis and without a penny to his name.

Belated Recognition Of Henry Johnson’s Heroism

Henry Johnson was interred at Arlington National Cemetery in a ceremony with full military honors, which was a pleasant surprise for his descendants.

Johnson’s son Herman — who was also a brave American soldier and had fought as a Tuskegee Airman during World War II — had led the effort to get official recognition for his father’s heroic deeds during the war. He was unaware that his father had been buried in Arlington until 2002.

“Learning my father was buried in this place of national honor can be described in just one word: joyful,” said Herman Johnson.

Thanks to his efforts, Henry Johnson was posthumously awarded a Medal of Honor by President Barack Obama in 2015 — 86 years after his death.

After learning about Henry Johnson, read about some other heroic Black soldiers who risked it all to fight for America. Then, check out these 41 stunning photos of the Harlem Renaissance.