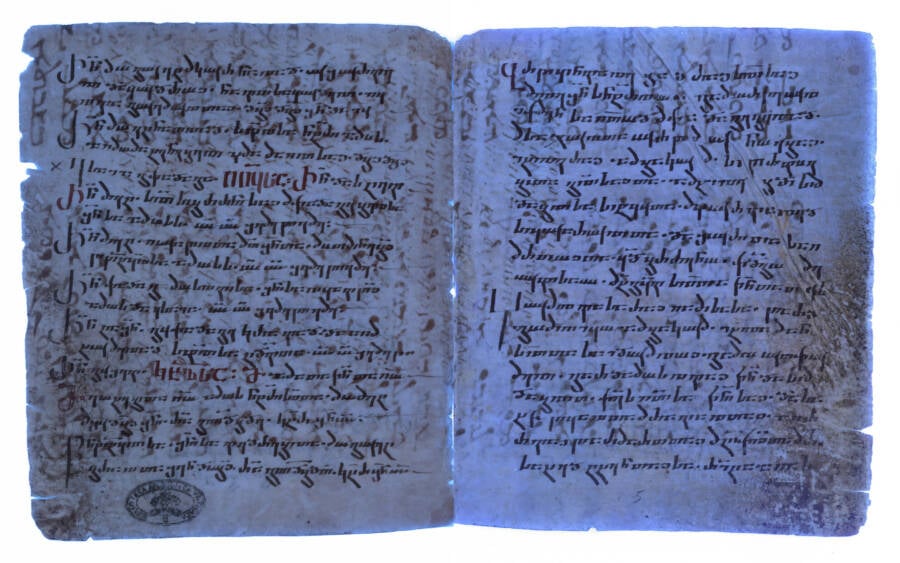

The 1,500-year-old text was uncovered thanks to the help of ultraviolet photography.

Vatican LibraryThe previously hidden Syriac translation of the Bible’s chapters 11 through 12 from Matthew.

Scientists have uncovered a “hidden” chapter of the Bible written about 1,500 years ago in a manuscript stored in the Vatican Library.

The previously lost section represents one of the earliest translations of the Gospels, written in Old Syriac script, which long eluded scholars for a rather simple reason: the text had been erased over a millennium ago.

Per a report from The Independent, the practice of erasing and reusing manuscripts was relatively common during the Middle Ages. Parchment was scarce, so when scribes were tasked with updating translations of the Bible and other books, it often meant fully replacing the original text.

Grigory Kessel, a researcher from the Austrian Academy of Sciences, analyzed one updated script, utilizing UV light to reveal traces of the ancient Syriac text. He and his team then uncovered the long-lost Syriac interpretation of chapters 11 through 12 from Matthew.

“The tradition of Syriac Christianity knows several translations of the Old and New Testaments,” he said. “Until recently, only two manuscripts were known to contain the Old Syriac translation of the gospels.”

One of these manuscripts is kept in the British Library in London; the other is stored in St. Catherine’s Monastery at Mount Sinai. Fragments of a third manuscript were also recently found during the “Sinai Palimpsests Project.”

The project aims to use state-of-the-art spectral imaging processes to recover erased texts from old manuscripts being kept at St. Catherine’s, the world’s oldest continually operating monastery.

The most recently discovered Syriac manuscript fragments found by Kessel in the Vatican Library were actually hidden under three layers of the manuscript. In other words, the Old Syriac text had been erased and written over, and then the same was later done to that text.

“The Gospel text is hidden in the sense that the early 6th-century parchment copy of the Gospels Book was reused twice,” Kessel explained to The Daily Mail, “and today on the same page one can find three layers of writing (Syriac – Greek – Georgian).”

Wikimedia CommonsThe Vatican Library, where the historic manuscript was analyzed.

And while it’s remarkable that Kessel and other scientists are able to use modern technology to reveal long-forgotten translations of ancient manuscripts, the potential for what this could reveal is even more incredible.

Although researchers have not yet released a full translation of the Syriac script, they have revealed some details that show how translations throughout history have obscured sections of Biblical passages.

For example, the original Greek translation of Matthew chapter 12, verse 1 reads: “At that time Jesus went through the grainfields on the Sabbath; and his disciples became hungry and began to pick the heads of grain and eat.”

The Old Syriac translation, however, reads, “…began to pick the heads of grain, rub them in their hands, and eat them.”

This translation was known as “Peshitta” and served as the official translation used by the Syriac Church by the fifth century and, according to Kessel, “quite often attests the Gospel text that is different from the standard Gospel text as we know it today.”

“As far as the dating of the Gospel book is concerned, there can be no doubt that it was produced no later than the sixth century,” Kessel and his team of researchers wrote in their study, which was published in the journal New Testament Studies. “Despite a limited number of dated manuscripts from this period, comparison with dated Syriac manuscripts allows us to narrow down a possible time frame to the first half of the sixth century.”

According to the team, the Syriac translations were written at least a century before the oldest Greek manuscripts that have survived, including the Codex Sinaiticus, the earliest known manuscript to contain the entire New Testament.

The Syriac manuscript observed by Kessel and his colleagues was then later reused for the “Apophthegmata patrum” in Greek, or the “Sayings of the Fathers,” in reference to early Christian hermits who practiced asceticism in the deserts of Egypt throughout the third century.

“Grigory Kessel has made a great discovery thanks to his profound knowledge of old Syriac texts and script characteristics,” said Claudia Rapp, the director of the Institute for Medieval Research at the Austrian Academy of Sciences.

“This discovery proves how productive and important the interplay between modern digital technologies and basic research can be when dealing with medieval manuscripts.”

After reading about this fascinating discovery, dive into the long history of who actually wrote the Bible. Then, find out what Jesus really looked like, based on scientific evidence.