A tragic flaw of most elementary history lessons is that we focus on teaching trivia. As it turns out, most of these "facts" are totally wrong.

Every schoolchild (in the United States, at least) grows up with the so-called “Great Man” theory of history etched into his or her mind. Rather than teaching trends and contingencies, which is hard, much of history education takes the form of memorizing the names of whoever went to the Moon, won some battle, or chopped down a cherry tree.

While bad enough as it is, many of the unimportant details we learn in school aren’t even accurate. While it’s true that Neil Armstrong really was the first man on the Moon, many of the other “firsts” your history book taught you were actually done by other people, often years or centuries before the guy who got famous did what he did. Thus, it falls to the Internet (again) to fix the shortcomings of the nation’s school systems.

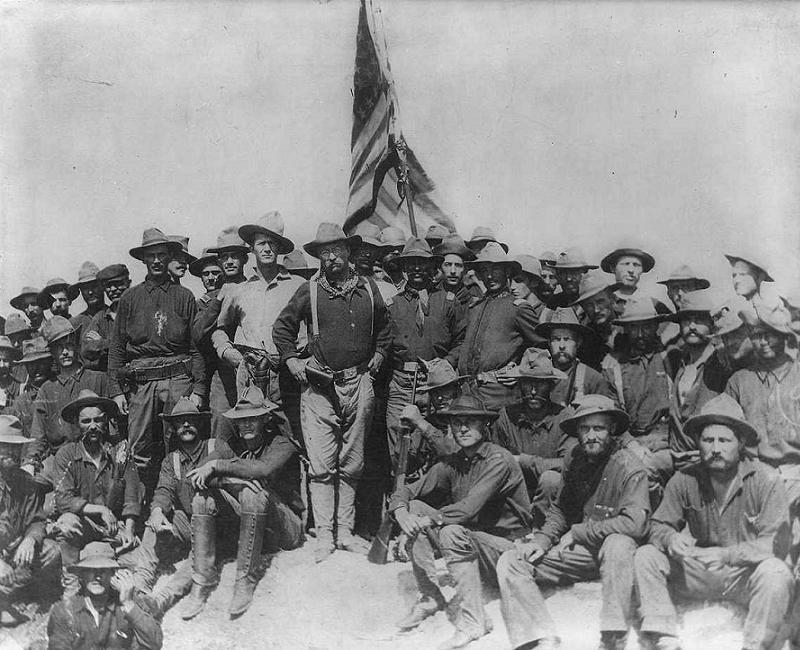

Teddy Roosevelt And The Rough Riders Braved The Battle Of San Juan “Alone”

Source: WordPress

The battle of San Juan Hill was a really big deal when it happened–like, president-making kind of big. The battle took place in three stages: an assault on the Spanish position at El Caney; a small redoubt just east of Santiago, Cuba; a charge up Kettle Hill, and then a run across the saddle road to San Juan Hill, the main objective. As we all know, Theodore Roosevelt practically won the battle all by himself and got to be president because of his awesome quotient (AQ).

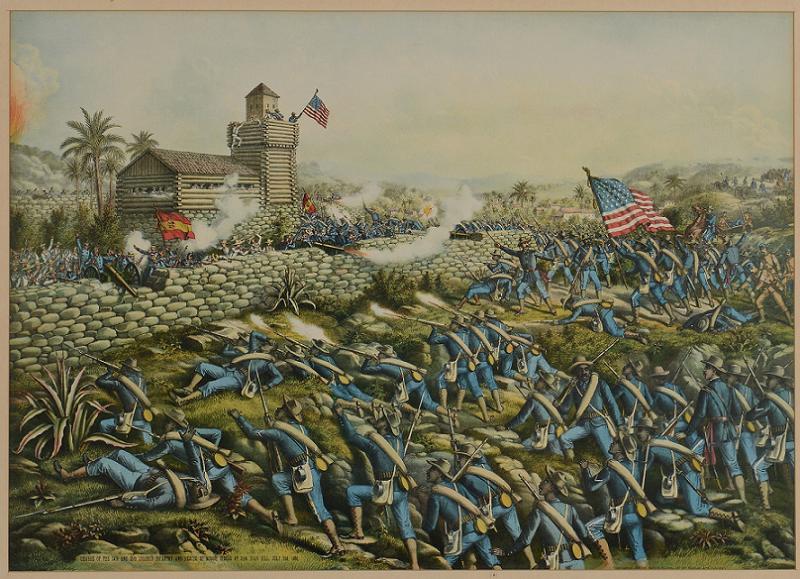

Source: Case Antiques

First, the facts of the battle: Around 8,000 US troops landed for the assault, which was scheduled for June 1, 1898. Because the US Army wasn’t clear on logistics at the time, most of the cavalry’s horses got lost on the way, leaving cavalry units, such as the Rough Riders, to fight on foot. About 500 Spanish soldiers spent much of the day holding off 5,000 American soldiers at El Caney, which American commanders eventually just decided to bypass for Kettle Hill. Since jogging past one fortified position to assault a second is absurdly dangerous work, the first unit sent was none other than the elite fighting force known as the Rough Riders.

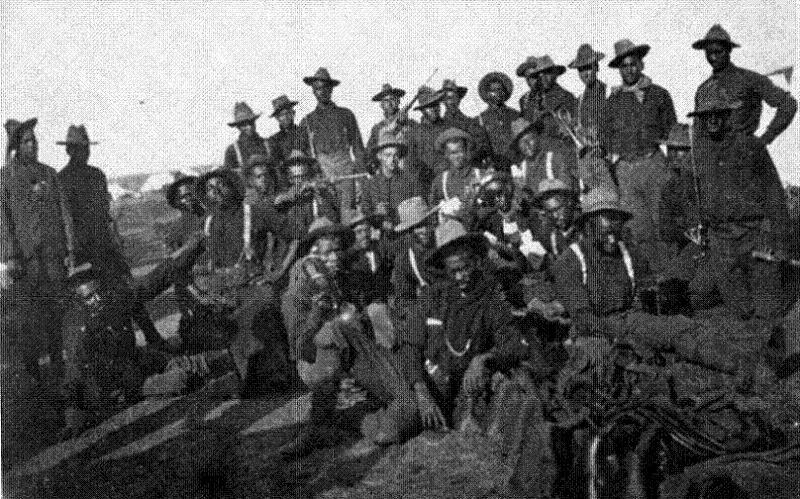

Source: Wikipedia

Just kidding–that task fell on the Buffalo Soldiers of the 9th and 10th Colored Cavalry. Though the Rough Riders were part of the charge, the black soldiers acted as the bullet sponges who marched first. This wasn’t 100 percent due to racism – the 9th and 10th were regular army units, staffed with professional veterans, rather than cowboys and East Coast dilettantes like Roosevelt, who actually brought his own publicist to the battle. It made sense to lead with the army’s strength when doing something really stupid.

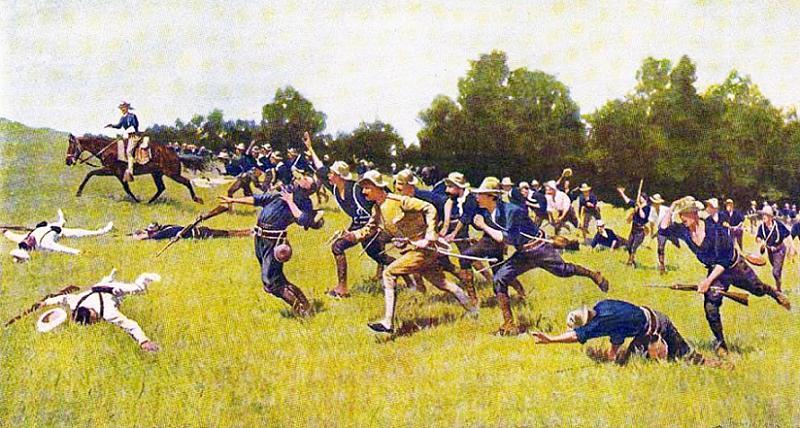

Source: Blogspot

Black and white units merged into a single column on the chaotic charge up Kettle Hill. After the position was secure, Lt. Col. Roosevelt, seeing people who weren’t him getting a bit of glory on nearby San Juan Hill, defied orders to hold the position and ordered a charge. Officially, nobody heard him, and he charged all by himself. Though, it’s worth considering that the men under his command might have preferred to be a little hard of hearing rather than charge after a glory-seeking nut immediately after securing a safe position. Roosevelt walked back to the line, passed orders for a proper charge, and finally led men up the hill that would buy him a place in history.

Source: Wikipedia

That is, of course, right after the all-black 24th infantry finished their advance up San Juan Hill, which probably made the walk much nicer for everybody else, future presidents included. Incidentally, the first soldier to enter the El Caney blockhouse, which was finally taken near evening, was Pvt. Thomas Butler of Baltimore, an infantryman of the 25th Colored regiment.

Jackie Robinson, Not The First Man To Break MLB’s Color Barrier

Source: The Sun Times

Major League Baseball integrated pretty quickly. As late as 1945, the “Gentleman’s Agreement” among team owners ensured that not a single player of black African descent was signed to any club’s major or minor league teams.

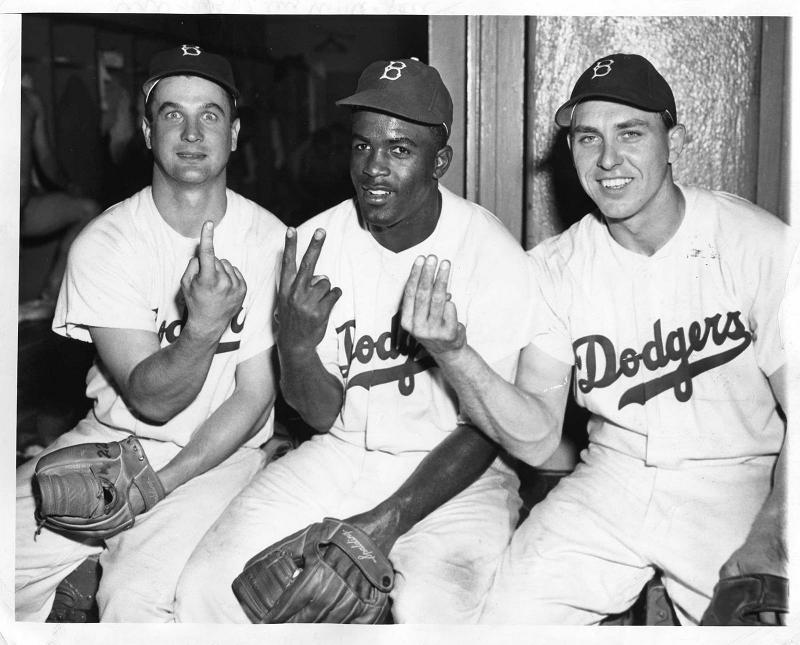

The world knows that Jackie Robinson broke that color barrier when he signed with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1946, though few remember that Larry Doby signed with the Cleveland Indians the same season. Within 10 years, the percentage of black MLB players was equal to their percentage in the US population. But the thing is that it didn’t all start with Jackie Robinson and Whats-his-face Doby.

Source: 90 Feet of Perfection

None of this is to diminish Jackie Robinson’s accomplishments. He walked out onto a field ringed with thousands of screaming crazies, and he probably spent his career eating more crap than a dung beetle. The whole time he played, he knew that every error would be blamed on his race, and that if he set a bad example, it could go hard for others trying to come up through baseball. Also, according to people who knew him, Jackie was a pretty good guy.

Source: David B. Stinson

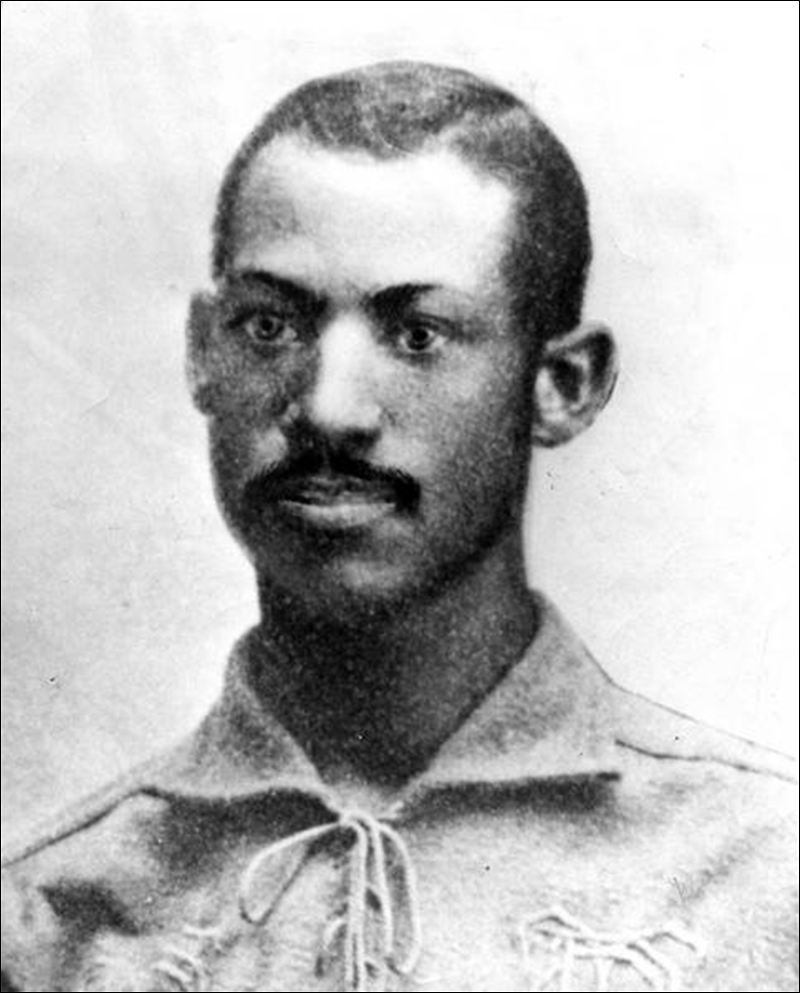

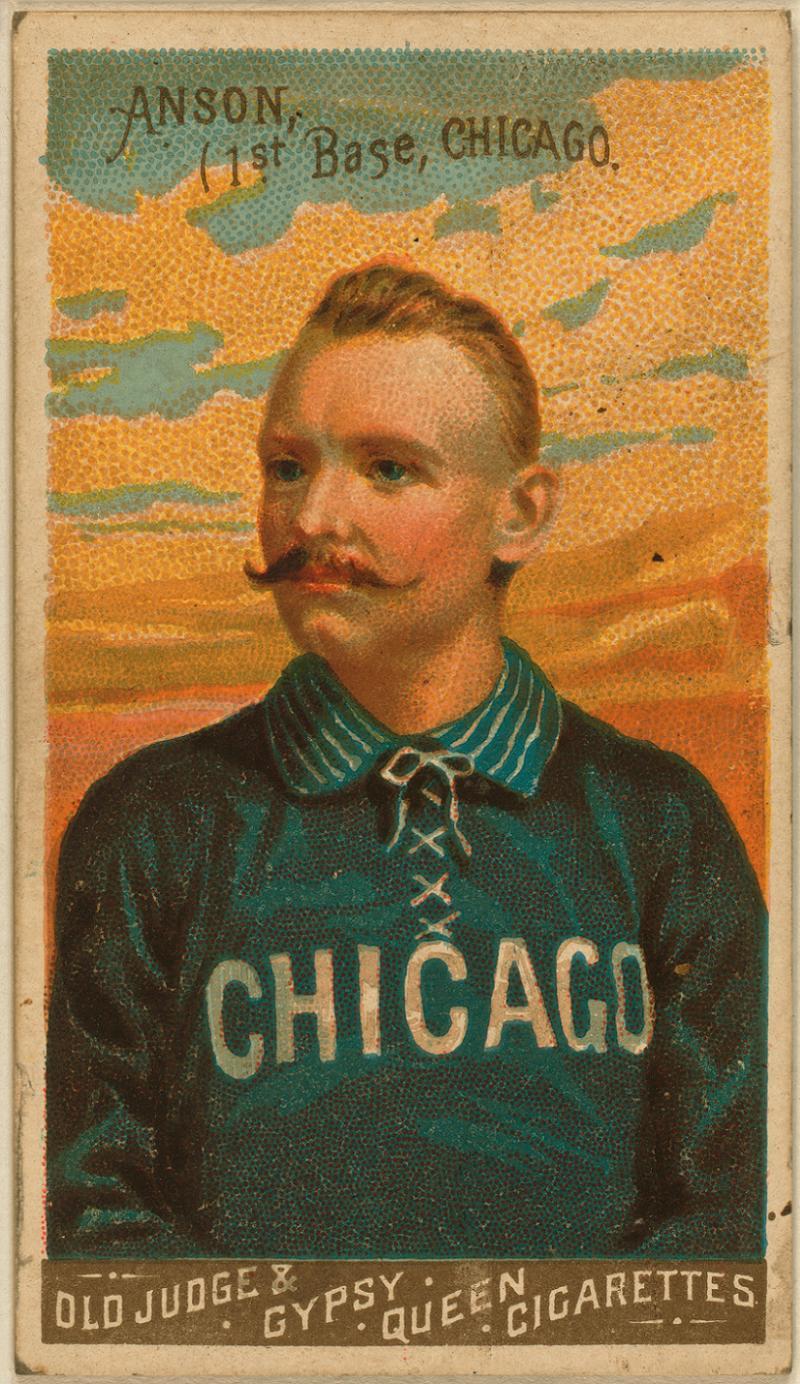

He just wasn’t the first black player in the Majors. That would be Moses Walker, who played with the Toledo Blue Stockings in 1884. A clue to why Walker only played one season may be found in the words of the Blue Stockings’ pitcher, Tony Mullane: “[Walker] was the best catcher I ever worked with, but I disliked a Negro and whenever I had to pitch to him I used to pitch anything I wanted without looking at his signals.” White Sox star player Cap Anson also threatened to boycott baseball if he was forced to play against a team with black players. Moses Walker spent the 1885-89 seasons with the minors before the color ban saw him, and the other black players – including Walker’s brother Welday – expelled from professional baseball for 60 years.

Cap Anson’s old-timey mustache wants you to know he objects to race mixing, but not to advertising cigarettes to kids. Source: MSU

That’s not to say there weren’t some hilarious attempts to get around the ban. Just before the 1901 season, Baltimore Orioles manager John McGraw tried to sign Charlie Grant as a second baseman. Grant was a relatively light-skinned black man, so naturally McGraw invented a fake Japanese name for him and tried to pass him off as “Charlie Tokohama.” Likewise, Jimmy Claxton, who was assumed to be a member of the Oklahoma tribe, despite being Canadian, joined the Oakland Oaks for a few games in 1916. Zee Nut baseball cards were even printed with his likeness. Then it came out that he wasn’t just American Indian, he was African-American too, and he was immediately fired.

Chuck Yeager, Not The First…Or Even Second…Pilot To Break The Sound Barrier

Source: Friendly Flusi

Here’s Space.com‘s hagiography of Chuck Yeager: “Yeager made his history-setting flight on Oct. 14, 1947 in an airplane he dubbed Glamorous Glennis, after his wife. The Bell X-1 rocket plane (which today hangs in the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum) passed Mach 1 following a drop from a B-29 airplane.”

To be clear, Chuck Yeager was the first pilot to achieve sustainable Mach-1 flight in an aircraft built for the purpose. He just probably wasn’t the first pilot to break the sound barrier. Or the second. He may not have been the third, either.

Source: Flight Journal

This is where a lot of unconfirmed anecdotes come in of pilots just barely touching supersonic speed, mostly while crashing, during World War II. For the most part, these can be discounted, as diving aircraft reach terminal velocity at rather low speeds. At terminal velocity, the drag on the airframe exactly balances the pull of gravity, so a tumbling aircraft can’t go much faster in free fall than it can in level flight.

Source: Defense Media Network

Some stories, however, have the ring of truth. During a 1943 test flight of the ME-262, German pilot Hans Mutke went into a dive at something like Mach 0.85. As his plane accelerated into the dive, he was buffeted by terrible turbulence, and his air-speed monitor jammed at Mach 0.95, which was probably a result of compressed air spoiling the sensor. After a few seconds, however, the turbulence stopped. Mutke hadn’t throttled back, nor had his speedometer unstuck and dropped.

When he did slow down, Mutke was again buffeted by turbulence. Then his speed readings began to drop normally and he landed safely. According to Willy Messerschmitt, the plane’s designer, the ME-262 was incapable of supersonic flight, not least because of a phenomenon known as “Mach dip,” in which planes begin a shallow dive near the sound barrier as the center of lift shifts backward along the wing’s surfaces. The only way to overcome this is with moveable ailerons on the tail, which Messerschmitt’s models didn’t have.

Mutke’s test plane, however, did have movable ailerons, which he claimed to have used to arrest the dive. It’s worth noting that Mutke didn’t know about that detail of supersonic flight, nor did he know about the turbulence-smooth sailing-turbulence pattern of breaking the barrier until 1948, when the details of Yeager’s flight were made public.

The Bell X-1 – In the Smithsonian Museum, right next to the Spirit of St. Louis. Source: Wikimedia

The XP-86 – Not in the Smithsonian. Nobody cares. Source: Seattle Pi