Scientists analyzed samples of fossil pollen from across Europe to estimate the death toll of the Black Plague and found evidence of a dramatic population decline in only seven of the 21 regions studied.

Wikimedia CommonsThough previous estimates said 50 million, new research says the experts have been very wrong about how many people died from the Black Plague.

We often imagine the Black Death as a terrible tidal wave that consumed Europe, killing an estimated 50 million people. While it’s impossible to truly know how many people died from the Black Plague, a new study based on pollen levels has challenged this staggering estimate. It suggests that while some European countries did suffer greatly from the plague, others escaped largely unscathed.

“We cannot any longer say that it killed half of Europe,” said Adam Izdebski, an environmental historian at the Max Planck Institute who co-authored a study on Black Death mortality that was recently published in the journal Nature Ecology. Now, other experts are rethinking just how many people the Black Death killed.

How Many People Died From The Black Plague?

The basic understanding of the Black Death goes something like this: Between 1346 and 1353, the bubonic plague spread with devastating swiftness across Europe and killed up to 65 percent of the population.

But did the plague pummel Europe equally? To answer that question, Izdebski and his co-authors looked for evidence within the European landscape. They decided to study ancient pollen levels.

Public DomainNew research is upending previous estimates about how many people died from the Black Plague, with new information suggesting it was nowhere near half of Europe.

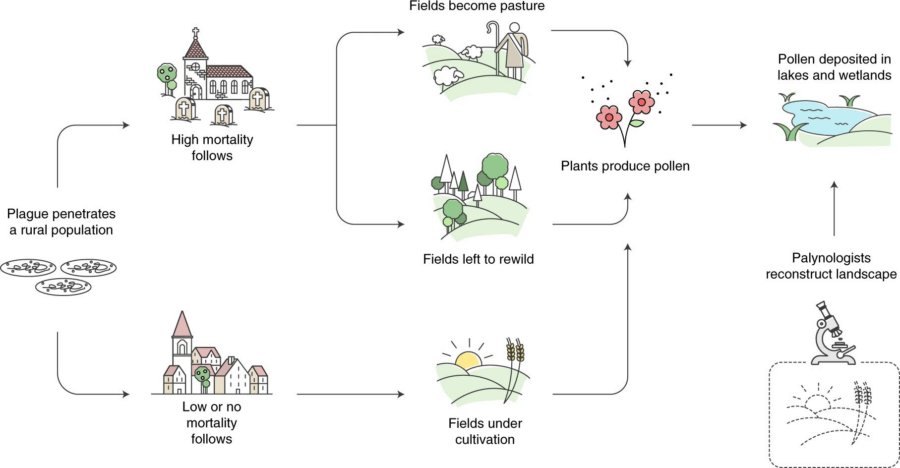

If a region lost a huge number of its population, they theorized, it would be reflected in the land. Workers would have died, farms would have gone untended, and the landscape would have changed.

Different plants create pollen of different shapes. When plants release this pollen, it can become trapped in muddy wetlands or lakes and preserved for hundreds of years. By studying this preserved pollen, Izdebski and his colleagues were able to determine which plants were producing the most pollen during the time of the Black Death.

An abundance of pollen from wheat and other crops would suggest that farming practices were not drastically interrupted during the pandemic. An increase in pollen from trees, shrubs, and other plants that aren’t typically found on farmland would show a disruption due to a high death toll from the plague.

“If a third or half of Europe’s population died within a few years, one might expect a near collapse of the medieval cultivated landscape,” Izdebski’s team wrote in The Conversation.

To The New York Times, Izdebski added: “Half of the labor force is disappearing instantly. You cannot maintain the same level of land use. In many fields you would not be able to carry on.”

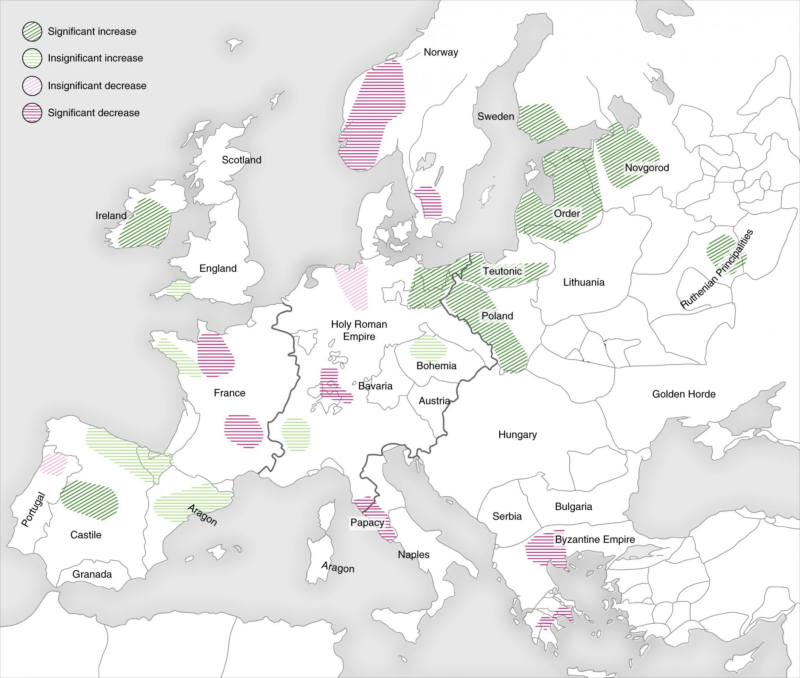

The research team analyzed fossil pollen samples from 261 sites in 19 European countries and made a surprising discovery. Just seven out of the 21 regions saw a dramatic shift — suggesting that, there, people did die of the plague in great numbers. But many of the other regions saw no shift at all. Some even showed an increase in human activity.

Hans Sell, Michelle O’Reilly and A.I.The study shows that, based on pollen levels, the Black Death did not affect all of Europe equally.

“We discovered that there were indeed parts of Europe where the human landscape contracted dramatically after the Black Death arrived,” Izdebski and his co-authors explained.

But in places like Catalonia and Czechia, “there was no discernible decrease in human pressure on the landscape.” What’s more, some places like Poland and central Spain showed evidence that “labor-intensive cultivation” had actually increased.

“This means the Black Death’s mortality was neither universal nor universally catastrophic,” the scientists wrote. “Had it been, sediment records of Europe’s landscape would say so.”

Why Some Think The Black Plague’s Death Toll Is Just As High As Previously Thought

However, Izdebski and his colleagues aren’t yet comfortable making a new estimate of how many people died from the Black Plague. But they do want to complicate the image of it as a universally devastating plague.

“That plague did not equally devastate every European region should not surprise us,” they wrote. “Not only will societies be affected and be able to respond differently, but we should not expect plague to always spread in the same way or for plague pandemics to be easily sustained.”

Some have lauded the new study, noting that it matches up with their own findings. Sharon DeWitte, a biological anthropologist at the University of South Carolina, has made similar assumptions about the pandemic’s death toll based on plague-era skeletons in London.

And Joris Roosen, the head of research at the Center for the Social History of Limburg in the Netherlands, noticed a comparatively small spike in inheritance tax in one Belgian province. Other, later outbreaks, he said, caused larger spikes, suggesting that the province didn’t suffer terribly in the 1340s and 1350s.

A.I., T.N., Hans Sell and Michelle O’Reilly.A simple flow chart shows how different plague mortality rates might have impacted the landscape.

But not everyone is convinced. John Aberth, who wrote The Black Death: A New History of the Great Mortality, still believes that the Black Death wiped out half of Europe’s population. He argues that the disease could not have impacted one region without impacting its neighbors.

“They were highly interconnected, even during the Middle Ages, by trade, travel, commerce, and migration,” Aberth said, suggesting that changing pollen levels could have reflected an influx of immigration labor. “That’s why I am skeptical that whole regions could have escaped.”

In the end, Izdebski and his colleagues want to paint a more complicated picture of the Black Death. And they hope that it can be used as humankind navigates current and future pandemics.

“While no two pandemics are the same, the study of the past can help us discover where to look for our own vulnerabilities and how to best prepare for future outbreaks,” they wrote. “To begin to do that, though, we need to reassess past epidemics with all the evidence we can.”

After reading about the new study on how many people died from the Black Plague, look through this list of Black Death symptoms. Or, see how the plague came to an end.