Between 1899 and 1951, J. C. Leyendecker drew 322 covers for the Saturday Evening Post, created thousands of advertisements for companies like Kellogg's and Ivory Soap, and invented the idealized "Arrow Collar Man."

Pink-cheeked sailors. Gibson Girls and their bouffants. Allegories for glory and victory aside intimate moments in the wake of war. Sleek men and slinky ladies, holiday kitsch, elegant homoeroticism, and All-American family scenes — these are the Art Nouveau meets Art Deco illustrations of J. C. Leyendecker. His style was one of a kind, and it still resonates a century later.

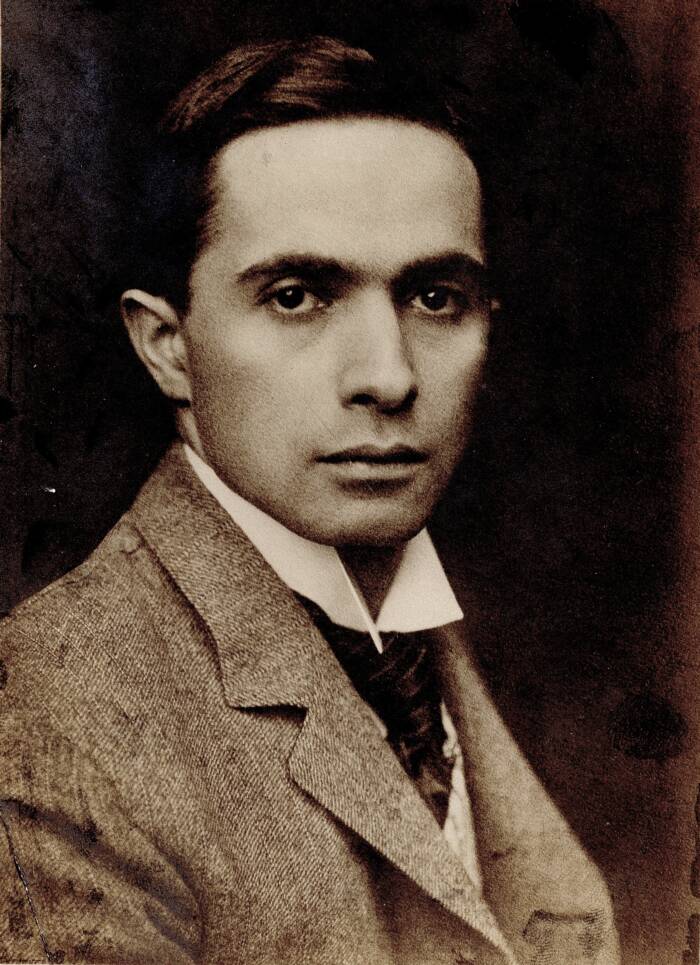

National Museum of American IllustrationJ. C. Leyendecker’s illustrations defined the ideal American man of the early 20th century.

While his name is less evocative than that of his protégé Norman Rockwell (who once proclaimed, “Leyendecker was my god”), his oeuvre is decidedly not. One of the most prestigious illustrators of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Leyendecker’s pictures took the pulse of the era. J. C. Leyendecker’s work was omnipresent, appearing on hundreds of Saturday Evening Post covers, advertisements for clothing and soap, military recruitment posters, and more.

Beyond periodicals and ads, Leyendecker innovated images so woven into American culture that they’re nearly folklore, from the familiar depictions of Santa Claus and the New Year’s Baby to the 1920s and ’30s heartthrob known as the “Arrow Collar Man.”

However, all of this elegance and creativity flowed from a life stricken with tragedy, shame, and secrets.

The Early Life Of A Neglected American Icon

Joseph Christian Leyendecker was born in Germany in 1874 to parents of modest means. His family immigrated to the United States in 1882, where Leyendecker studied at the Art Institute of Chicago and apprenticed with the J. Manz Engraving Company. He moved through the ranks quickly, going from errand boy to illustrating a client’s private Bible and winning a Century Magazine competition.

Public DomainJ. C. Leyendecker circa 1895.

Ultimately, J. C. Leyendecker and his brother Frank, who was also an aspiring artist, traveled to Paris to study at the Académie Julian. They returned to Chicago in 1898, but 24-year-old Leyendecker soon traded the Windy City for the Big Apple. New York is where the famed artist experienced his greatest triumphs — and his greatest tragedies.

Just a year after his big move, Leyendecker was commissioned to illustrate his first Saturday Evening Post cover. Over the next five decades, his work would appear on the front of the magazine a total of 322 times.

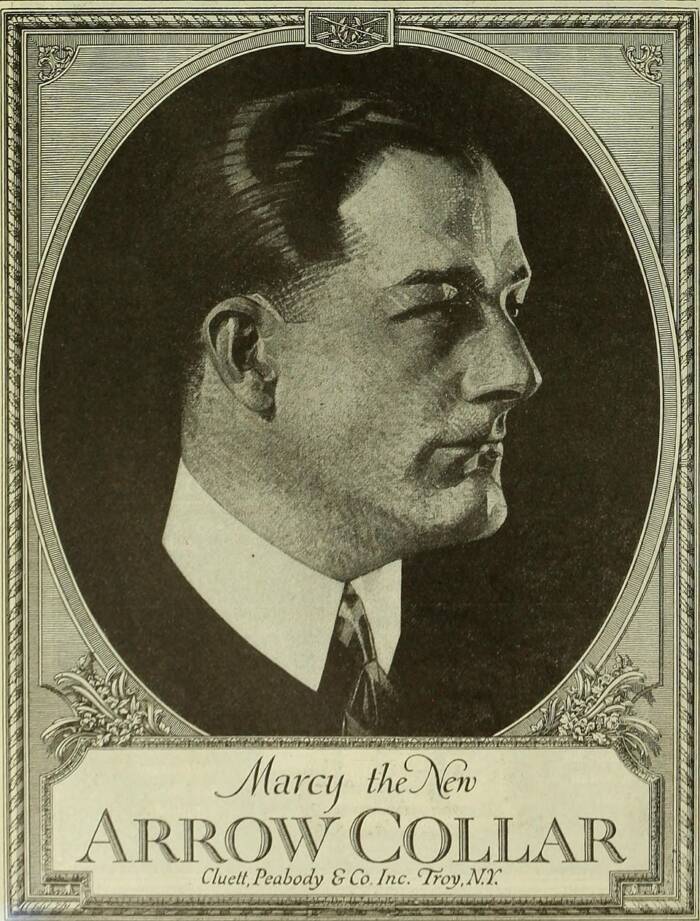

Soon, Leyendecker was creating ads for brands like Kellogg’s and Ivory Soap. However, his most iconic collaboration was with the men’s clothing company Cluett, Peabody & Co., which hired him to create advertisements for their “Arrow” detachable shirt collars. Leyendecker’s “Arrow Collar Man” quickly became the embodiment of the early 20th century. Every man wanted to be him, and he visualized the American Dream of the time.

The Saturday Evening Post/Wikimedia CommonsThe Arrow Collar Man was one of J. C. Leyendecker’s most stylish contributions to American culture.

Even as the top hats of the turn of the century became the pageboy caps and the Gatsby tuxedos of the 1920s, J. C. Leyendecker’s suave men sold an American lifestyle of privilege, style, and a sort of lust for beautiful masculinity. Leyendecker’s ads worked, earning Cluett, Peabody & Co. $32 million per year (over $1 billion in today’s currency).

His pretty, All-American men were based on a series of models, but one became recurrent. Charles Beach was Leyendecker’s favorite muse — and almost certainly his lover.

J. C. Leyendecker And The Golden Age Of American Illustration

Halloween HJB/FlickrJ. C. Leyendecker’s art often featured beautiful, well-dressed men, and many believe his work exuded homoeroticism.

Whether Leyendecker made the Arrow Collar Man in Beach’s image or whether the man he’d been bringing to life from his imagination onto paper simply appeared in front of him one day, it is impossible to say. What is certain is that these two men worked and lived together for nearly 50 years beginning in 1903, when Beach first went to Leyendecker’s studio in New York looking for work as a model.

In 1914, on the eve of World War I, Leyendecker built a magnificent mansion in New Rochelle, New York, where he and Beach lived until Leyendecker’s death in 1951. A staff member’s son who spent a great deal of time at Leyendecker’s home told The New York Times in 1998 that Beach was “a striking man with a very deep voice,” which he would often use “to bark at you,” while Leyendecker was “very patient and gentle… They were both lonely people.”

J. C. Leyendecker also had a close relationship with Norman Rockwell, who took inspiration from the artist. “[Rockwell] was virtually Leyendecker’s protégé,” said Roger Reed, the president of Illustration House in Manhattan and an expert on the art of the era. “His early work bears even the same kind of brush strokes, although toned down and on a smaller scale. In those early years Rockwell slavishly imitated Leyendecker. Leyendecker was clearly one of his strongest influences, not just in technique but in the whole definition of American culture.”

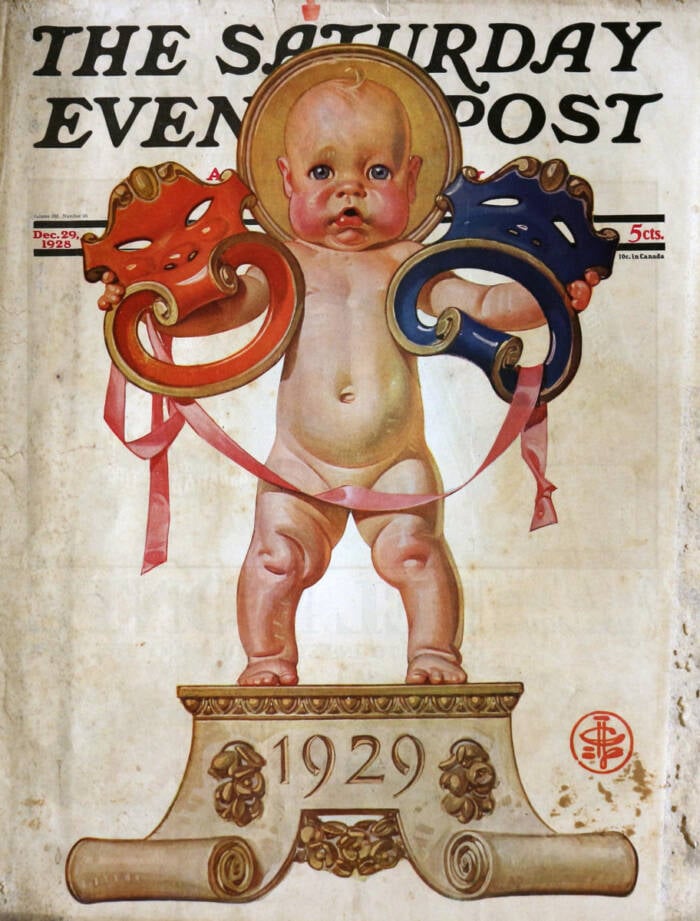

The Saturday Evening Post/Wikimedia CommonsThe New Year’s Baby, a symbol that J. C. Leyendecker popularized.

War allegories, famous likenesses, football players in action, domestic scenes — Leyendecker’s illustrations ran the gamut, but some of his most enduring creations were his holiday covers.

Not only did he help define the American concept of Easter and Christmas (including contributing to the now traditional red-suited, pink-cheeked, jolly Santa Claus), but Leyendecker was also responsible for popularizing the New Year’s Baby motif. Symbolizing rebirth, Leyendecker’s baby was a staple of The Saturday Evening Post for over 40 years, and it remains a common image today.

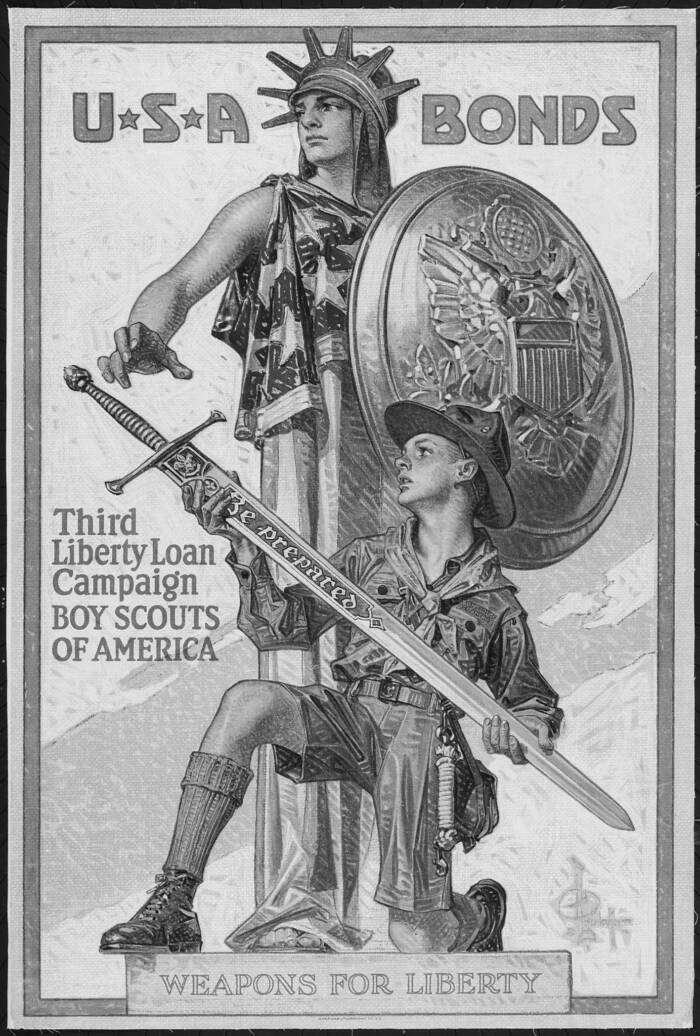

Leyendecker didn’t only draw for commercial purposes, though. During both World Wars, he put his prowess into recruiting troops and selling war bonds. While other artists chose to depict the blaze of war in action scenes, Leyendecker stayed mostly in the realm of the immediate. His intimate scenes, depicting a lover’s goodbye, a little boy’s fantasy of war, and even a soldier mourning a brother in arms at his gravesite showed the human side of war.

U.S. National Archives and Records AdministrationA World War I bond poster by J. C. Leyendecker.

J. C. Leyendecker’s career rose and fell with the 20th century. With the rise of photography, his commissions became fewer, and his debts mounted. Likewise, his personal life was no less complicated, particularly when it came to romance. An engagement to a woman in the 1920s was reportedly scuttled after a jilted Beach threatened to expose their love.

In 1951, while working on a Christmas cover for the The American Weekly, Leyendecker had a heart attack and died at age 77.

The Enduring Legacy Of J. C. Leyendecker

While J. C. Leyendecker’s legacy initially seemed to have died with him, his downfall was only temporary. In 1977, he was added to the Society of Illustrator’s Hall of Fame, and in 2014, one of his famed Santa Claus illustrations sold for over $200,000 at Christie’s.

Public DomainOne of J. C. Leyendecker’s American archetypes: the football player.

His work even continues to inspire other artists to this day. George Lucas, the creator of Star Wars, looked to Leyendecker’s Saturday Evening Post covers as a lesson in storytelling through images. And Carol Cutshall, a costume designer for the Interview with the Vampire series, told AMC Talk in 2022 that she referenced Leyendecker’s Arrow Collar Man in her fashion designs for the undead.

“He made famous the Arrow Shirt Man and he was the male standard of beauty,” Cutshall said. “He became such a big thing that he sold millions of shirts just because everyone wanted to be that man in his illustrations… [Louis and Lestat’s] style sense in many ways is a love letter to Leyendecker.”

As such, J. C. Leyendecker’s world of glamor and style, his stories, his scenes, and even his tragic love story have shaped the world forever.

After reading about iconic 20th-century illustrator J. C. Leyendecker, discover how naturalist Ernst Haeckel mixed science and art. Then, look through Ansel Adams’ stunning black-and-white images of the American West.