On April 18, 1775, William Dawes and Paul Revere were both dispatched to warn colonists in Massachusetts that the British were coming — so why is only Revere's story celebrated today?

Public DomainAn oil painting of William Dawes.

As the British army advanced in April 1775, a brave rider raced through the countryside to warn American colonists that “the British were coming.” His name was Paul Revere, and he’s been celebrated in poems, statues, and reenactments. But on that fateful night, Revere wasn’t alone. He was joined by another member of the Sons of Liberty named William Dawes.

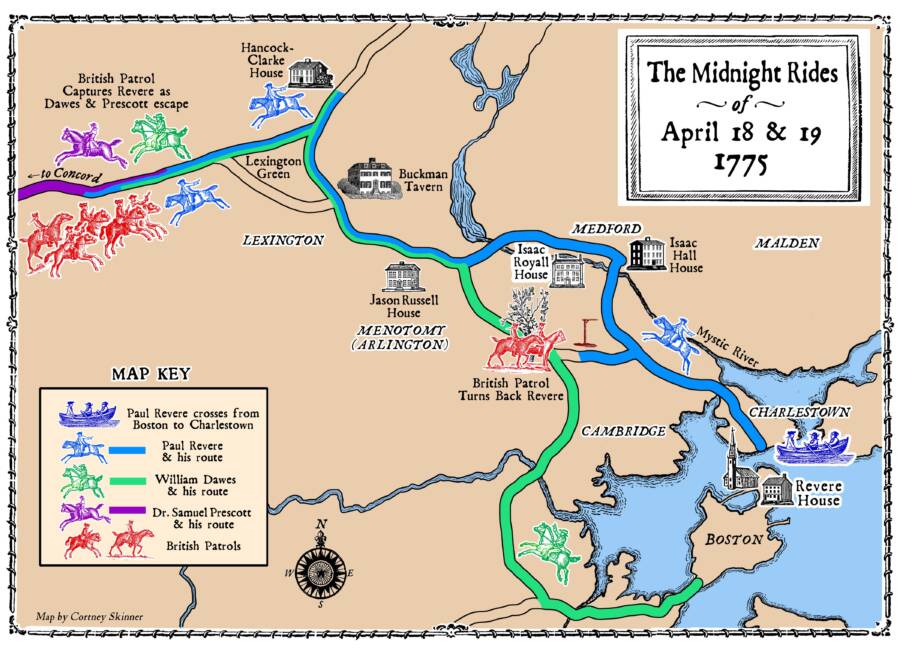

Like Revere, Dawes was dispatched from Boston to spread word about British troop movements. While Revere took the shorter path, “by sea,” Dawes took the longer, more dangerous route, “by land.” The two men reconvened in Lexington, warned John Hancock and Samuel Adams about the British, and set out to Concord together.

Yet in the retelling of the night, which came on the eve of the Battle of Lexington and Concord, only Revere’s name has been remembered.

Who Was William Dawes?

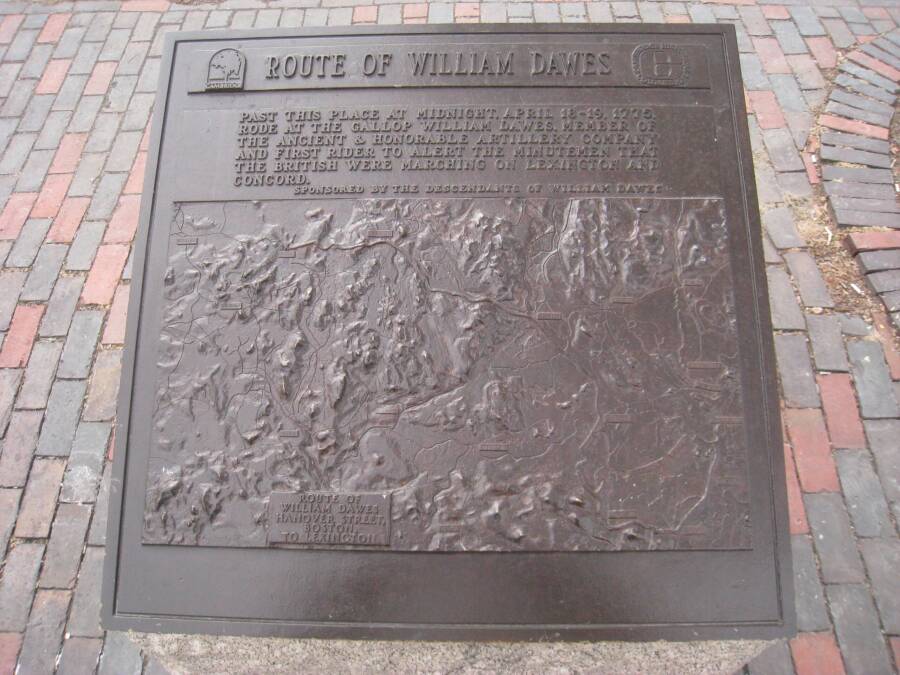

Born on April 6, 1745 in Boston, William Dawes belonged to the fourth generation of the Dawes family to live in the British colonies. Though he trained as a tanner, he later pursued a more military career, first in a Boston militia unit, and then in the Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company of Massachusetts. In 1772, Dawes became a second sergeant.

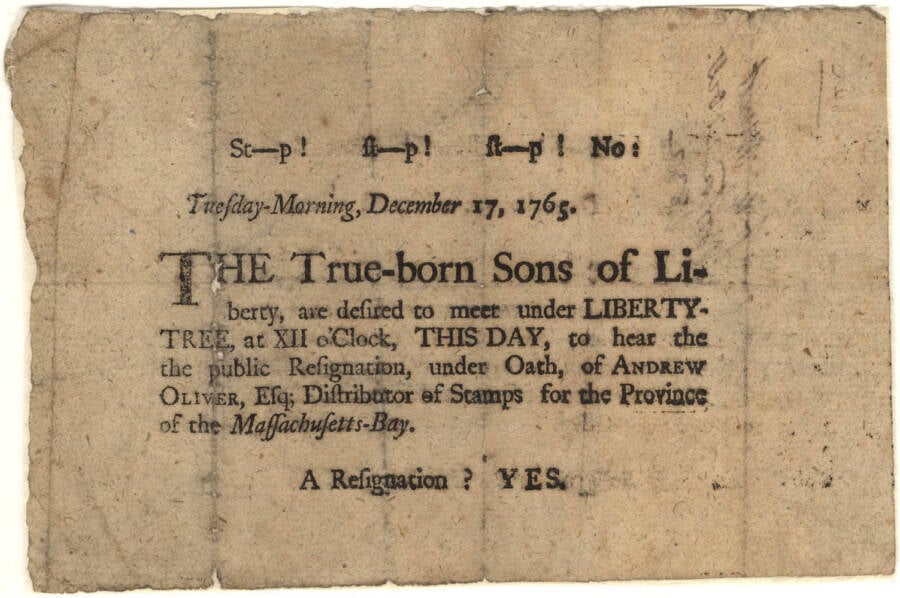

But William Dawes was also a member of more covert organization. Disillusioned with British rule over the colonies, he joined the Sons of Liberty, and soon set out to support their anti-British efforts.

Massachusetts Historical SocietyA Sons of Liberty handbill from 1765.

The Sons of Liberty resisted British rule in the years before the Revolutionary War, perhaps most famously by organizing the 1773 “Boston Tea Party” in protest of the hated Tea Act. Dawes was an enthusiastic member. He stole British cannons, possibly transporting them to Concord, and earned the trust of Dr. Joseph Warren, one of the organization’s leaders.

As such, when Warren heard that British troops were preparing to march toward Lexington and Concord, he called up two of his most trusted riders — Dawes and Paul Revere — and tasked them with an important mission.

The Midnight Ride Of William Dawes

When Warren called upon William Dawes and Paul Revere on April 18, 1775, he was deeply concerned. He’d heard through the Sons of Liberty intelligence network that the British were going to move toward Lexington and Concord to look for military supplies and to possibly arrest Sons of Liberty leaders John Hancock and Samuel Adams.

Public DomainPaul Revere’s ride became famous, though he and William Dawes had the same mission.

Warren tasked Dawes and Revere to ride toward Lexington and Concord in order to alert colonists in the countryside and to warn Hancock and Adams. Revere would leave Boston by sea, while Dawes would take the longer route from Boston to Roxbury, and across a bridge on the Charles River.

His ride would not only be longer, but riskier, as Dawes would have to pass British sentries outside the city limits. But Warren had chosen William Dawes to take the land route for a reason. Because of his work as a tanner, he had reason to come and go from Boston. Plus Dawes, naturally witty and friendly, had also become a familiar face to some of the British sentries — though he was equally capable of sneaking out of the city undetected.

Dawes left Boston at around 9 p.m., and Revere followed an hour later. As planned, Dawes was able to slip past the British sentries on Boston Neck

Cortney Skinner/Paul Revere HouseA map showing William Dawes and Paul Revere’s routes on April 18, 1775.

Not long after Dawes left the city, the British sealed the gate and refused to let anyone leave Boston. But by then, Dawes was already alerting the countryside to the British advance.

A Close Call With British Troops

At midnight, Paul Revere reached Lexington. Dawes, who had the longer route and a slower horse, arrived about 30 minutes later. After warning Hancock and Adams, they rode next toward Concord.

Along the way, they were joined by Samuel Prescott, a patriot doctor from Concord out for a late night ride (possibly to visit a girlfriend). But the trio didn’t get far. At around 1:30 a.m., they ran into a British patrol.

Wikimedia CommonsA plaque in Cambridge, Massachusetts shows the route of William Dawes, which went through the town.

Revere was captured; Prescott managed to steer his horse over a stone wall and ride to Concord. And William Dawes, with British troops in pursuit, had to think fast. According to Dawes family lore, he led his British pursuers into a farmhouse and shouted, “I’ve got two of them – surround them!” as if he were surrounded by his fellow patriots.

The ruse worked and the British rode off, though Dawes was thrown from his horse and had to return to Lexington on foot.

On the next day, April 19, 1775, the American Revolution began with the Battle of Lexington and Concord. Though Dawes had already served his country admirably, he would go on to fight in the Battle of Bunker Hill. In September 1776, he also became a major and worked as a quartermaster. He died in 1799, having lived to see his dreams of American independence realized.

Public DomainA depiction of the Battle of Lexington and Concord, which marked the beginning of the Revolutionary War.

Yet William Dawes is all but forgotten today.

Why History Remembers Only Paul Revere

On April 18, 1775, Paul Revere and William Dawes were tasked with the same mission. In the end, Dawes accepted the more difficult and riskier route, and he managed to evade capture after Revere was arrested. So why is Paul Revere remembered — and William Dawes forgotten?

It’s certainly true that William Dawes was less prominent than Paul Revere, who was a well-known silversmith. Revere also wrote first person accounts of his mission, while even Dawes’ contemporaries didn’t know his name (a guard who met Dawes on April 18, 1775, remembered him as “Mr. Lincoln.”)

But the reason why Paul Revere is more remembered than William Dawes largely has to do with a poem written almost a century after their ride.

In 1861, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow published “Paul Revere’s Ride.” Longfellow, who had possibly read a biography of Revere, wrote a poem making it sound like Revere was the only rider who warned colonists. According to the National Park Service, this so upset one of William Dawes’ descendants that he self-published a book entitled William Dawes and His Ride with Paul Revere in 1878. For good measure, he also sent it to Longfellow, who wryly noted that the book “convicts me of high historic crimes and misdemeanors” for leaving Dawes out of the story.

Richard Wood/Wikimedia CommonsA statue of Paul Revere in Boston.

Still, some people remembered William Dawes. In 1896, Helen F. Moore even wrote a poem reclaiming Dawes’s place in history:

‘Tis all very well for the children to hear

Of the midnight ride of Paul Revere;

But why should my name be quite forgot,

Who rode as boldly and well, God wot?

Why should I ask? The reason is clear —

My name was Dawes and his Revere.

Now that you’ve heard of William Dawes, discover the story of Sybil Ludington, the 16-year-old girl who allegedly also rode through the night to warn colonists about the British. Or, discover the forgotten stories of 12 women who made a difference during the Revolutionary War.