Joan of Leeds created a makeshift dummy to throw Archbishop Melton off track. She then fled to a town 30 miles away and was never seen again.

Committing to the lifelong pursuit of being a nun and living in a convent is one that requires extreme commitment — particularly in the 14th century. For Joan of Leeds, a rather rebellious English nun at St. Clement’s Nunnery in Yorke, a change in pursuits required extreme measures — namely, escape.

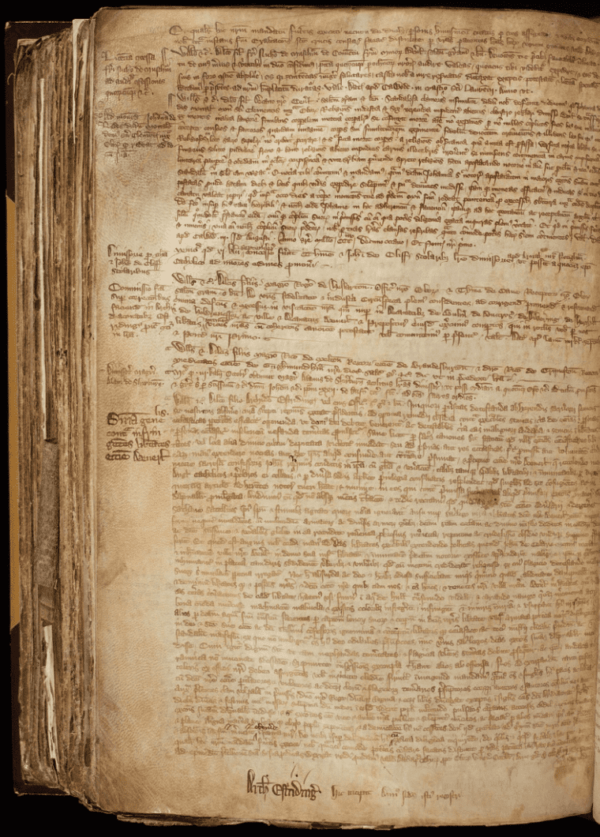

Archivists at the University of York recently uncovered Joan’s fascinating backstory while translating and digitizing 16 registers of York’s archbishops used to document current events between 1304 and 1305.

Pexels

What they found was a tale of intrigue and admirable cunning, as Joan faked her own death by creating a dummy “in the likeness of her body” and placing it among actual corpses before running away, HuffPost reported.

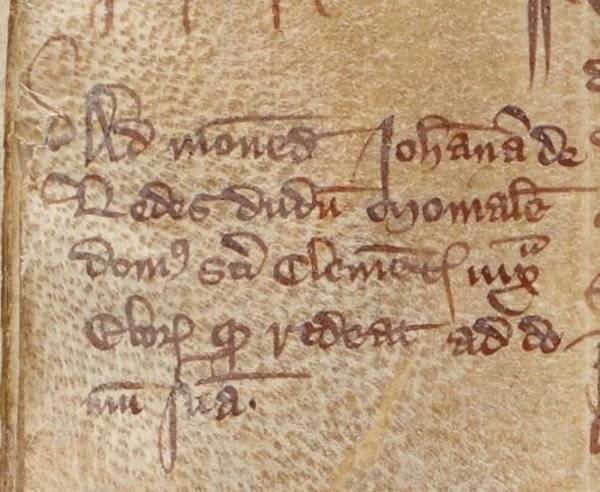

University of YorkArchbishop Melton’s note, claiming Joan was “seduced by indecency” to “pursue carnal lust.” 1318.

Changing one’s mind about life in a nunnery was a substantial faux pas at the time, due to both the gravity of the religious commitments being broken, as well as the limited agency women experienced in medieval times. York’s religious leaders were highly displeased at her actions.

“She now wanders at large to the notorious peril to her soul and to the scandal of all of her order,” wrote Archbishop of York William Melton in a record book dated 1318, The Guardian reported.

From the surfaced evidence alone — detailing Joan using a dummy, burying it in a place that would strongly point to her being dead — escaping the convent’s strictures was clearly a priority that outweighed any potential consequences or retribution.

A note in the register explained that she “impudently cast aside the propriety of religion and the modesty of her sex” by faking her death “in a cunning, nefarious manner” which had her simulate “a body illness” where she “pretended to be dead,” before placing her makeshift lookalike “in a sacred place” among real, dead members of her religious order.

York Archbishop’s Register/University of YorkThe archbishop of York’s register detailing Joan’s daring escapade.

After successfully fooling her Benedictine sisters into burying the dummy, Joan fled St. Clements and traveled around 30 miles to reach the town of Beverley, The Church Times reported. When Archbishop Melton discovered what she had done, he commanded a subordinate to retrieve her.

“Having turned her back on decency and the good of religion, seduced by indecency, she involved herself irreverently and perverted her path of life arrogantly to the way of carnal lust and away from poverty and obedience,” wrote Melton.

It’s entirely unclear if Melton’s church officials ever located Joan, if she was to create a new life for herself, or whether she even returned to the convent on her own volition.

What is fairly well established, however, is that the long-term career choices for women at the were essentially relegated to serving at a nunnery or participating in an arranged marriage — or working for a living, usually in agriculture, retail, real estate, or crafts.

University of YorkSarah Rees Jones examines the archbishop’s register. 2019.

“There were limits to how far they could succeed in or even enter many professions, still less positions of public authority,” said University of York historian Sarah Rees Jones, lead archivist of the digitizing project.

In the early 14th century, vowing to become a nun was a viable path for women as young as 14. While this wasn’t officially forced upon women, the commonly voluntary life choice was, admittedly, bestowed upon young girls and monks by ardent religious parents quite often.

Whether this was Joan’s story — a young girl who never wanted to become a nun, live in a convent and sacrifice her freedoms, and made a daring escape to lead a better life — will possibly never be known, for certain. As it stands, however, it seems as though Joan’s overarching goal of leaving without a trace was pretty well accomplished.

After reading about Joan of Leeds and her creative escape from St. Clement’s Nunnery, learn about the excavation of serial killer H.H. Holmes that proved he hadn’t faked his death. Then, learn about the European fugitive who faked his own death and was discovered living in a castle.