Historians debate whether or not Judge Holden ever really existed, but the Blood Meridian antagonist was said to have been the most ruthless member of the Glanton gang of scalp hunters that roamed Mexico and the American Southwest in the mid-1800s.

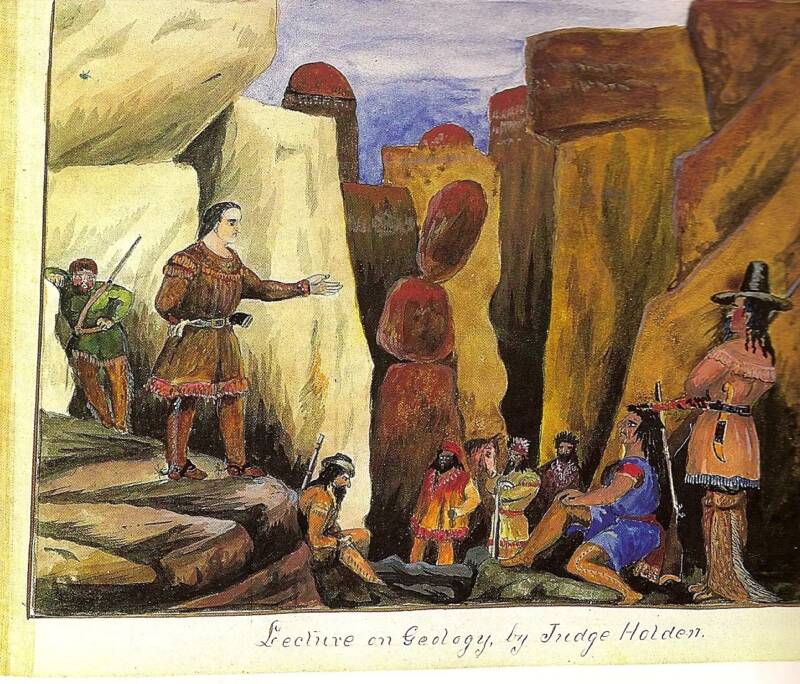

John D. Salvatore/DeviantArtAn illustration of Judge Holden by John D. Salvatore based on the character described in Blood Meridian.

Author Cormac McCarthy is not known for writing lighthearted novels, but for all the violence and darkness his books are famous for, few are quite so unrelenting as Blood Meridian. It was published in 1985 and billed as a historical epic. The book follows a fictional teenager and his run-ins with a group of scalp hunters who prey upon Native Americans along the border of the United States and Mexico in the mid-1800s. Perhaps the most vicious of these men is named Judge Holden.

Unlike many of McCarthy’s other novels, however, the characters of Blood Meridian are not entirely fictional. The scalp hunters in his book are known as the Glanton gang, a very real group of people who actually did hunt down Native Americans for a bounty in the 1850s. And the novel’s primary antagonist, Judge Holden — described as physically massive, highly educated, and incredibly skilled — is based on a purportedly real person, too, though his true history is blurry.

In fact, outside of McCarthy’s novel, the only other historical mention of Judge Holden comes from the autobiography of Samuel Chamberlain, a soldier, author, and painter who also rode with the Glanton gang for a time and chronicled this period of his life in his book My Confession. Still, from Chamberlain’s description, Holden was every bit as terrifying as he seems in McCarthy’s novel.

So, did Judge Holden really exist? And if so, what happened to him?

The Glanton Gang And Scalp Hunting In 19th-Century America

The Glanton gang, led by John Joel Glanton, was one of the most infamous scalp hunting groups in 19th-century America. Composed of ex-soldiers, outlaws, and other men accustomed to violence, the gang was originally contracted by Mexican authorities in 1849 to hunt down Apaches and other Indigenous groups in northern Mexico.

Mexico, which was grappling with raids by Native warriors at the time, offered bounties for each scalp brought in as proof of a kill, essentially turning human flesh into a macabre currency. Initially, this practice served Mexico’s goal of weakening resistance against settlers by the Indigenous people who lived in the region. However, the system soon spiraled out of control, as bounty hunters found it easier — and more profitable — to target non-combative communities. Glanton and his gang quickly turned to indiscriminate killing, slaughtering not only Native groups but also local civilians and even travelers along the Rio Grande.

Public DomainAn 1850s depiction of scalping, the grisly act Judge Holden and the Glanton gang carried out countless times.

This led to escalating violence and lawlessness that alarmed Mexican officials, who eventually changed course and forbade the gang from operating in their territory. The state of a Chihuahua even put a bounty on their heads instead.

As they lost official contracts, the Glanton gang shifted to outright banditry, attacking anyone they encountered, including rival scalp hunters. The group’s eventual downfall came after they set up a ferry crossing on the Colorado River and began extorting travelers. In 1850, Quechan warriors hoping to create their own monopoly on the ferry business in the area ambushed the gang, killing Glanton and most of his men.

But despite the notoriety of the Glanton gang, perhaps none of its members were as feared as Judge Holden.

The Real Judge Holden, John Joel Glanton’s Right-Hand Man

Historical records in the early 19th century, particularly in the remote lands of northern Mexico and the southwestern U.S., weren’t often complete. Thankfully, Samuel Chamberlain, a painter, author, and soldier from New England, recalled his time with the Glanton gang in his memoir, offering the only true firsthand source of Judge Holden’s brutality.

“Who or what he was no one knew but a cooler blooded villain never went unhung; he stood six feet six in his moccasins, had a large fleshy frame, a dull tallow colored face destitute of hair and all expression,” Chamberlain wrote of Holden in My Confession: Recollections of a Rogue. “But when a quarrel took place and blood shed, his hog-like eyes would gleam with a sullen ferocity worthy of the countenance of a fiend.”

Chamberlain wrote that Holden’s only desires were blood and women. Around campfires, stories were told of Holden’s past, when he bore another name, and the various crimes he committed. Holden was ruthless — and he didn’t care who he killed.

“[B]efore we left Fronteras a little girl of 10 years was found in the chapperal, foully violated and murdered,” Chamberlain wrote. “The mark of a huge hand on her little throat pointed [Holden] out as the ravisher as no other man had such a hand, but though all suspected, no one charged him with the crime.”

Public DomainAn illustration from Samuel Chamberlain’s memoir showing Judge Holden giving a lecture on geology.

Despite Judge Holden’s depravity, Chamberlain also described him as “the best educated man in northern Mexico.” He spoke several languages, rode a horse better than nearly anyone else, and had significant knowledge in botany, geology, and mineralogy. Chamberlain said Holden could play the harp and the guitar “and charm all with his wonderful performance and out-waltz any poblana of the ball.”

Chamberlain, for his part, did not regard Holden kindly. In fact, he went as far in his writing as to say that he “hated him at first sight,” yet Holden always treated Chamberlain with kindness: “He would often seek conversation with me and speak of Massachusetts and to my astonishment I found he knew more about Boston than I did.”

Since there are no further records of Judge Holden, it’s unknown what happened to him after his time with the Glanton gang. He was likely killed alongside his fellow scalp hunters during the Qeuchan attack, but nobody can know for certain.

Indeed, with such little information about Holden available, especially from contemporary sources, some historians have wondered if his name was actually a pseudonym — and, if so, who the real Judge Holden may have been.

Theories About The ‘True Identity’ Of Judge Holden

Amateur historians and McCarthy fans alike have long attempted to determine Judge Holden’s true identity, if indeed the man described in Chamberlain’s book went by an alias. Two of the most popular theories identify either journalist Charles Wilkins Webber or geologist John Allen Veatch as candidates.

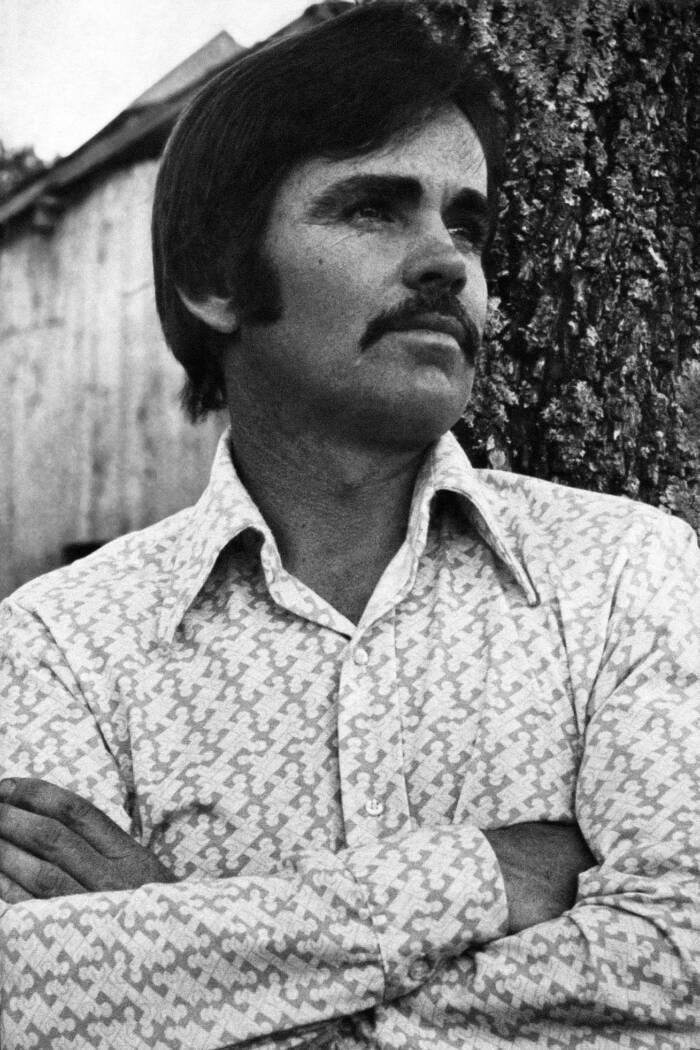

Public DomainCormac McCarthy, the author of Blood Meridian.

The case for Veatch is relatively straightforward. Holden was described as having extensive knowledge of geology, and Veatch did lead a scalp hunting party into Mexico at one point. Meanwhile, Webber was a prestigious journalist and explorer from Kentucky who tried to head a mining expedition to the Colorado and Gila Rivers in 1849, the same time Judge Holden would have been active in the area.

Of course, Judge Holden’s name didn’t appear in writing again until Cormac McCarthy wrote Blood Meridian. His description of Holden, which is, of course, based on Chamberlain’s memoir, closely mirrors the supposed historical figure:

“[A] massive, hairless, albino man who excels in shooting, languages, horsemanship, dancing, music, drawing, diplomacy, science and anything else he seems to put his mind to. Despite his almost infinite knowledge, which he can use to achieve anything he desires, Holden favors a life of murder and hate… He is also the chief proponent and philosopher of the Glanton gang’s lawless warfare.”

Scholars have called McCarthy’s Holden “perhaps the most haunting character in all of American literature,” but if the man he’s based on actually existed, Judge Holden may also be one of the most haunting figures in all of American history.

After learning about the figure who inspired Cormac McCarthy’s Judge Holden, read about Roy Bean, the eccentric Wild West judge known for outrageous rulings. Then, learn about the mobster who inspired the character of Tony Soprano.