The Kaiten was not only a weapon of destruction but a symbol of the strength of the Japanese pilots' spirit.

US Navy/ Wikimedia CommonsShips in port at Ulithi in late 1944. The Kaiten hide under the water.

It was the early hours of the morning on November 20, 1944. The sun was rising off the bow of the USS Mississinewa, and rays of orange light were breaking over the small port of Ulithi in the Caroline Islands. For the young men onboard the oil tanker, this brilliant dawn rising over a tropical paradise might well have been one of the most beautiful things they had ever seen. For many, it would also be the last.

Beneath the crystal waters of the port, an unseen enemy waited. Lieutenant Sekio Nishina was gliding towards the Mississinewa inside a Kaiten, a weapon that he himself had helped invent. Also on board was an urn holding the remains of Lieutenant Hiroshi Kuroki, the weapon’s co-creator who had perished while piloting one of the early prototypes. In a few moments, the two friends would be reunited in death.

At 5:47 AM, Nishina’s Kaiten struck the side of the Mississinewa and detonated. Within seconds the more than 400,000 gallons of aviation gas in the ship’s hold ignited along with the 90,000 gallons of fuel oil. As the few men lucky enough to be above deck and still intact leaped into the sea, a wall of flames more than 100 feet high moved towards the ship’s magazine.

Moments later, the magazine ignited, ripping a massive hole in the hull. Ships docked nearby moved in to rescue the survivors and put the fire out, but nothing could now extinguish the inferno. After a few hours, the Mississinewa turned over and sank beneath the waves. 63 men were dead and the lives of many others changed forever due to horrific burns.

Nearby, a Japanese submarine observing the initial explosion through the periscope reported to their superiors that, based on the size of the explosion, the attack must have managed to sink an aircraft carrier. This was the news the Japanese Admiralty had been desperate to hear. The Kaiten had lived up to its name.

“Kaiten” roughly translates into English as “heaven-shaker,” and it reflects the purpose the weapon was meant to serve.

The Kaiten

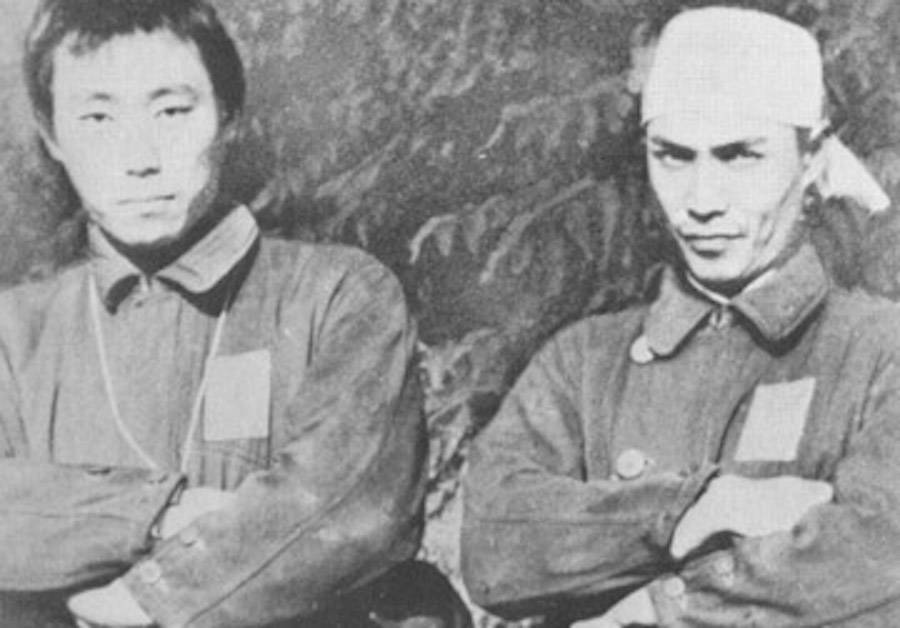

Imperial Japanese Navy/ Wikimedia CommonsSekio Nishina and Hiroshi Kuroki

By the end of 1943, the early Japanese successes in the Pacific had given way to a series of catastrophic defeats. In June 1942, the US Navy, re-armed and hungry for vengeance, smashed the Imperial Navy at Midway. From there, the tide shifted as US forces hopped from island to island, driving ever closer to Japan itself.

Outnumbered, outgunned, and facing an enemy with nearly limitless resources, the Japanese needed something miraculous to stave off the defeat. So, they turned to the only resource they had left: their young men. For years, the Japanese had gone to great lengths to instill fanatical devotion in their soldiers. Now, they were going to try to turn that devotion into a weapon that would save Japan.

The Kaiten were born out of this desperation and the wishful thinking that fanatic self-sacrifice could make up for Japan’s military weakness compared to the Allies. Lieutenant Hiroshi Kuroki and Lieutenant Sekio Nishina of the Japanese Navy designed and tested the first prototypes, which were essentially nothing but human-guided torpedos. The Kaiten never really evolved in practice to be anything else.

The only significant modifications were the introduction of controls and basic air filtration systems, along with an upgraded 3, 420 lb warhead. Over 300 of these Type 1 Kaiten were eventually built. Though the Japanese continued modifying the design of the Kaiten until the end of the war, the Type 1 was the only version to actually see use.

Needless to say, the Type 1 was a dangerous craft to pilot. Water frequently leaked into the pilot’s compartment and the engine, which often caused the craft to explode prematurely. Early designs allowed the pilot to open the Kaiten in an emergency, but the escape hatch was eventually phased out because the pilots refused to use it. Once a pilot was in a Kaiten, they knew that they weren’t coming out again.

They had made a decision to die for their country and the Emperor. In fact, most did.

Imperial Japanese Navy/ Wikimedia CommonsA Kaiten Type 1 being launched

Kaiten pilots were volunteers between the ages of 17 and 28. No previous experience with submarines was necessary. The pilots were trained to use basic instruments to navigate ships above the surface. Once they mastered this, they would be allowed to dive in a Kaiten. The final phase of training was using the instruments on board to navigate past underwater obstacles and guide the craft into surface vessels.

At least 15 men died during this training. The most common cause was colliding into the surface ships. Though there were no explosives on board, the force of the collision was frequently enough to lead to fatal injuries. But if a pilot could survive through a few weeks of training, they would be given the opportunity to pilot a Kaiten in a real attack run against US ships.

Nishina’s attack on the Mississinewa was probably the first successful Kaiten mission, and it was a good example of why the Kaiten wasn’t the war-winning weapon the Japanese hoped it would be.

Nishina’s was one of eight Kaiten launched that day. Though all eight Kaiten pilots died, he was the only one to score a hit. As tragic as the loss of the Mississinewa was, it wasn’t enough to change the balance of power in the Pacific.

Dangerous Missions

A far more common outcome of Kaiten attacks was the Japanese submarine transporting them being sunk before it got within range of its target, usually with a tremendous loss of life.

Over 100 Kaiten pilots died during training or during attacks. Over 800 more Japanese sailors were killed transporting them to their targets. Meanwhile, US estimates for losses due to Kaiten attacks put the death toll at less than 200 men. Ultimately, the Kaiten managed to sink just two large ships: the Mississinewa, and a destroyer the USS Underhill.

Wikimedia CommonsHigh school girls bid farewell to a departing kamikaze pilot

The real question, of course, is what motivated men to willingly pilot torpedos to their deaths. In fact, it was probably the same thing that has motivated soldiers to risk their lives throughout history. In the final testament of one Kaiten pilot, Taro Tsukamoto, he stated, “[I]… must not forget that I am foremost a Japanese. … May my country flourish forever. Goodbye, everyone.”

The Kaiten pilots believed that their nation needed their lives, and many were happy to give them. It’s not hard to imagine that if the situation were desperate enough, people from any nation would have been willing to do the same.

Of course, it also speaks to a spirit that was unique among the Japanese of that generation. They had been taught since childhood that they had a duty to sacrifice their life for their country and emperor. More importantly, they were expected to do so. The shame of refusing to die motivated pilots perhaps as much as a genuine desire to lead suicide attacks.

It would be a mistake to think that an entire generation of men was brainwashed. Many simply felt that they were forced to sacrifice themselves. Hayashi Ichizo was ordered to fly his aircraft in a kamikaze attack off Okinawa. In his final letter to his mother, he wrote, “To be honest, I cannot say that my desire to die for the emperor is genuine. However, it is decided for me that I die for the emperor.”

When one looks for an explanation, that mixture of pride and coercion is probably the closest one can come to it. But in the end, not even the fanatical devotion of these young men was enough to save their country from defeat. The Kaiten program was really only another tragic episode in the most tragic war in human history.

Next, read more about some of the Japanese’s most horrific war crimes. Then, read about Unit 731, Japan’s World War II human experimentation project.