The combined efforts of the British government, religious groups, and individual volunteers saved 10,000 Jewish and non-Aryan children from certain death.

Getty ImagesPolish children rescued via Kindertransport arrive in London, February 1939.

Great Britain was so disturbed by the events of Kristallnacht, the pre-war peak of open violence against Jews in Germany, that they opened their borders to Jewish children for refuge. Through trains and the occasional airplane, the British Kindertransport, or children’s transport, evacuated Jewish and other non-Aryan children from the Nazi regime.

The operation would save nearly 10,000 young lives who would likely otherwise have met the same gruesome fate as their parents.

Kristallnacht And Organization In Britain

The Nazis two-day spree of destruction began on Nov. 9, 1938, on what’s known as Kristallnacht, the “Night of Broken Glass,” which set a precedent for the Holocaust. During those two days, the Nazis destroyed Jewish homes and businesses, and beat and killed their owners. Some 100 German Jews lost their lives in that 48-hour span.

Horrified by this, a delegation of concerned citizens from Britain on Nov. 21, 1938, stood before the British Parliament and requested that the country grant temporary asylum to children from Germany, Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Austria — not yet anticipating that these events foreshadowed the harrowing genocide to come.

The group of concerned citizens consisted of members of the Central British Fund for German Jewry (CBF), prominent British Jewish leaders, and representatives of non-Jewish religious organizations alike.

British politicians, though, were wary of the potential backlash from accepting refugees at a time when jobs were already scarce in Britain but agreed to provide relief to the children at no expense of their own people. Therefore, the Jewish and non-Jewish organizations would have to fund the operation themselves.

The government agreed to allow an unspecified number of unaccompanied children up to the age of 17 into the country, as long as they “would not be a burden on the state.” The British stipulated that a 50-pound bond had to be posted for each child — costs which were ultimately covered by the CBF and other charitable organizations and private individuals. Britain also hoped that other countries like the United States would see their refugee efforts and subsequently offer their own aid.

British Home Secretary Sir Samuel Hoare announced the decision by declaring:

“Here is a chance of taking the young generation of a great people, here is a chance of mitigating to some extent the terrible suffering of their parents and their friends.”

George W. Hales/Fox Photos/Getty ImagesSome of the 235 Jewish child refugees on their arrival from Vienna at Liverpool Street Station, London, July 1939.

The Kindertransport

The evacuations of the children became known as “Kindertransports” which is almost literally translated at “children’s transport.” All efforts were organized by volunteers on the ground in Europe.

Lists were drawn up of the children deemed most at risk of being deported and back in Britain radio appeals were broadcast in an attempt to find foster homes for the rescued children. Hundreds of Britons answered the call (many of whom were not Jewish) and those who volunteered were vetted and their homes inspected before approval.

Jews were not the only ones choosing to send their children off on the Kindertransports. A variety of social, economic, and political backgrounds boarded the trains to the relative safety in Britain.

The Movement for the Care of Children from Germany – later known as the Refugee Children’s Movement (RCM) was responsible for rounding up and transporting the children. They met them with hot chocolate at the trains in some cases.

The first Kindertransport left an orphanage that was destroyed during Kristallnacht in Berlin departed on Dec. 1, 1938 and arrived in Harwich, Great Britain the following day.

Infants were looked after by older children, and anything the children wanted to bring with them had to fit into a suitcase that they could carry. One child was reported to have brought dirt from his hometown. They were not allowed to take valuables out of the country, but some parents would hide them in their children’s clothing anyway.

For parents, the announcement of the Kindertransport was bittersweet.

Photo by Fred Morley/Getty ImagesTired and alone, 8-year-old Josepha Salmon, the first of 5,000 Jewish and non-Aryan refugees, arrives at Harwich on Dec. 2, 1938.

As painful as it was to send their children off to a foreign country alone, the only alternative was sentencing them to almost certain death at home. Every single parent who put their child aboard a British rescue train faced with a heart-wrenching decision; they chose to save their young sons and daughters with the knowledge that they might never be reunited.

Agonizing Departures

Alfred Traum was just ten-years-old when his parents put his sister Ruth and him on a Kindertransport train.

Traum’s father, a crippled World War I veteran, knew that he and his wife Gita didn’t stand a chance of escaping their native Vienna. However, thanks to the Kindertransport, his children did.

Alfred recalled how his mother held his hand through the train window until the last possible minute, not letting go even as the train began to move. Even as her grip slipped away, she jogged along the platform until they faded out of sight. They never saw each other again.

Traum’s parents, uncle, aunt, cousin, and grandmother were all deported from Vienna to the Trostenets extermination camp. They were shot upon arrival and tossed into a mass grave — a fate Alfred and Ruth would not have escaped if not for the Kindertransport.

Life In England For Kindertransport Refugees

Most of the foster families welcomed their additions with open arms. Children yet to be sponsored went to re-purposed summer camps, boarding schools, or hostels supported by private donors and charities. But other children saw different fates. Teenage girls were often taken in as servants. For some of the children, their heritage was all but erased as a few were given new names, identities, and religions.

When Britain did officially enter the war, children aged 16-17 of enemy countries were taken into custody in internment camps.

The experience of the Kindertransport was initially a traumatic one as the children were whisked from their parents to a country where most did not speak the language.

Many of the children did, however, come to appreciate the country that had saved them. As Traum explained, “until we got there, we didn’t feel totally free.”

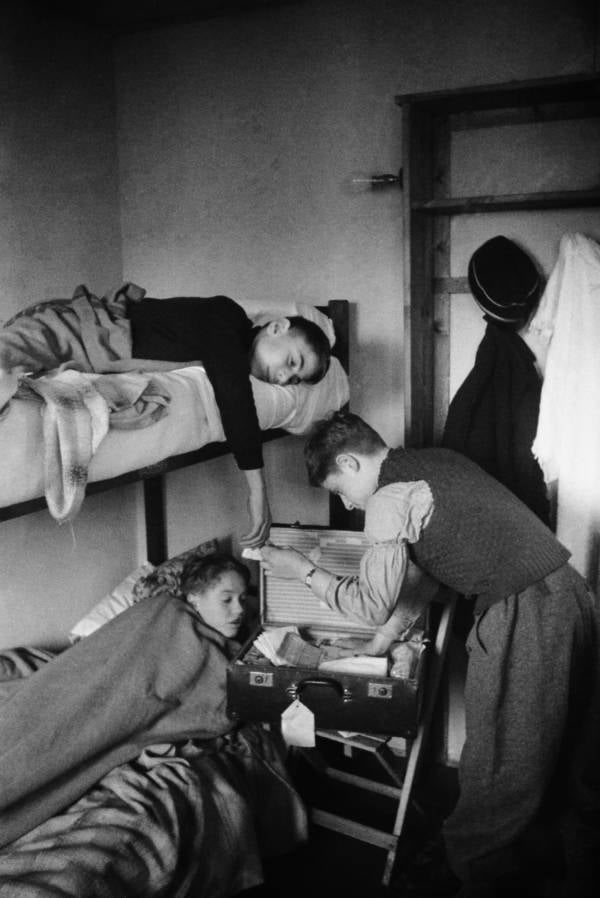

Photo by Gerti Deutsch/Picture Post/Hulton Archive/Getty ImagesThree refugee children at a holiday camp at Dovercourt Bay near Harwich after arriving in Britain, December 1938.

Indeed, many of the children had positive experiences in Britain. They grew to love their adopted country and think of themselves as British citizens. Approximately 1,000 of the refugee children joined the British Army once they were of age — and gave their lives to fight against the evil that had forced them out of their homelands.

The Aftermath

The Kindertransport organizers saved children until the last possible moment. The final train of young refugees left Germany on Sept. 1, 1939. It was the very day Hitler invaded Poland, and two days before Britain declared war on Germany. Individuals on the ground in the Netherlands continued to organize evacuations until their own country was invaded in May of 1940 — effectively placing continental Europe under Nazi control.

Over the course of 10 months, the Kindertransport brought nearly 10,000 endangered children to England. This achievement was remarkable — not only for the sheer number of lives saved — but because it was organized by ordinary people from all different backgrounds, all with the common goal of protecting a stranger against a great evil.

After this look at the uplifting tale of the Kindertransport, read about the woman who saved 2,500 children during the Holocaust. Then, check out some stunning footage of the liberation of Dachau. Finally, read more about Nicholas Winton.