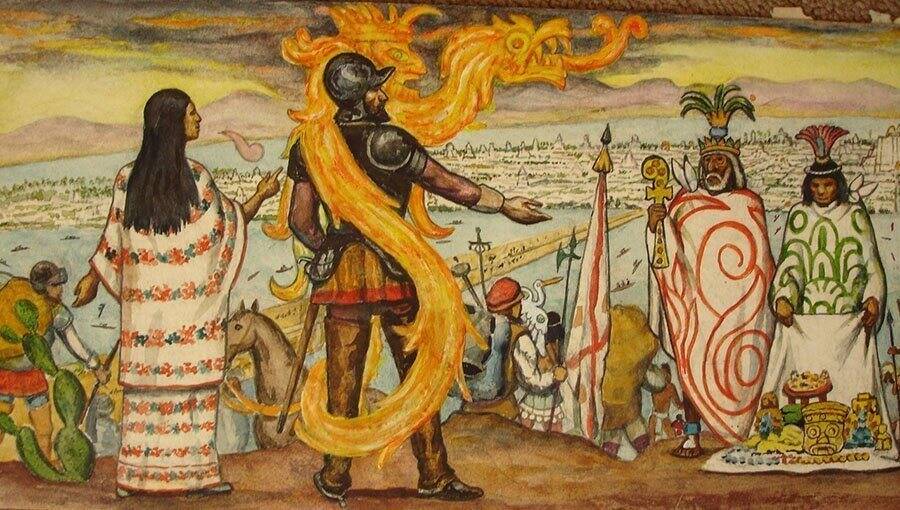

Also known as "Doña Marina," La Malinche advised Hernán Cortés to victory over the Aztecs — but perhaps she had little choice in the matter.

Wikimedia CommonsLa Malinche became a trusted liaison to the Spanish conquistadors in the 16th century. She also went by “Malintzin” or “Doña Marina.”

La Malinche was a native Mesoamerican woman of a Nahua tribe who became a trusted adviser and translator to Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés. Her guidance proved instrumental in his takeover of the Aztec empire and by some accounts, she was also Cortés’s lover and mother of his child.

La Malinche’s contribution to the Spanish conquest of the Aztecs in the 16th century, however, has made her a polarizing figure among modern Mexicans, many of who now utter her name as an insult.

This is her complicated story.

Who Was La Malinche Before She Met Cortés?

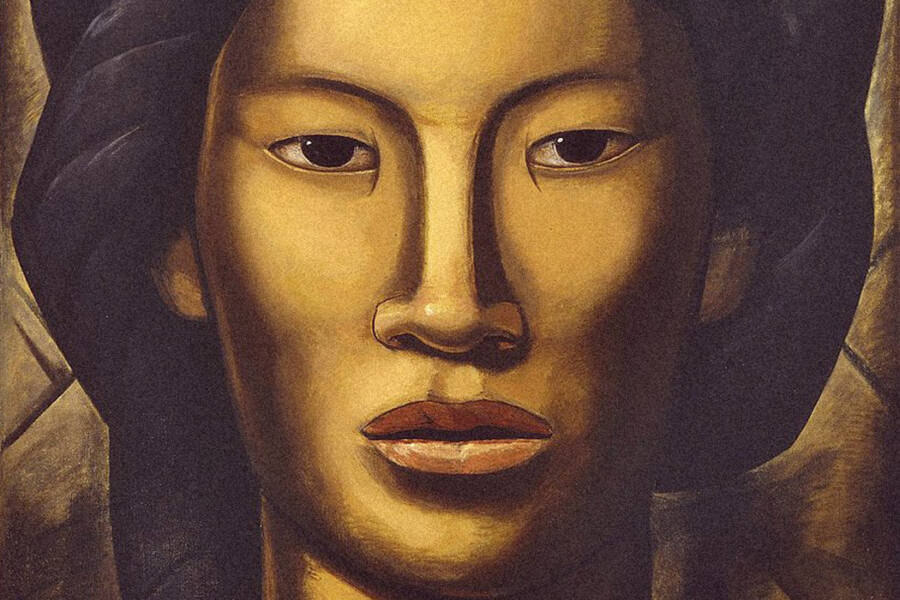

Wikimedia CommonsA portrait of the controversial figure La Malinche.

Little is known for certain about La Malinche, who is also known as Malintzin, Malinal, or Malinalli. What is known about her was compiled from secondhand historical accounts. Historians estimate that she was born sometime in the early 1500s to an Aztec cacique, or chief. As such, La Malinche received a special education that provided her with the skills she later leveraged with the Spanish.

But La Malinche was betrayed by her own mother when her father died. The widow remarried and sold La Malinche to slave traders who, according to historian Cordelia Candelaria, sold her to a Mayan chief in Tabasco. There she remained until Hernán Cortés and his Spanish army arrived at the Yucatán Peninsula in 1519.

Meanwhile, La Malinche’s mother performed a fake funeral for her to explain her disappearance to their community.

At the same time, Cortés and his men made their way across the peninsula in search of an abundance of silver and gold in the Aztec empire. They slaughtered hundreds of tribal warriors and robbed the natives of their resources along the way.

Wikimedia CommonsHernán Cortés, the Spanish explorer known for his violent conquests in South America.

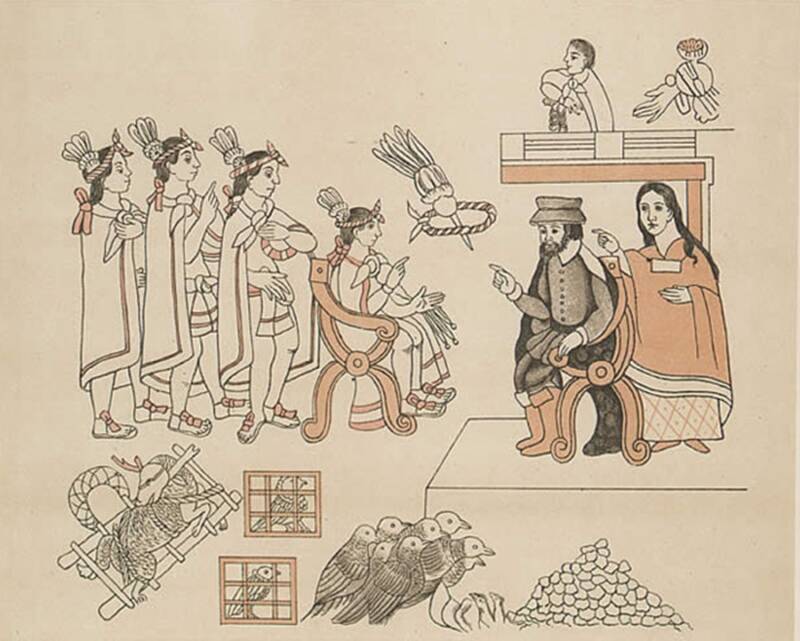

When Cortés arrived in Tabasco, a Mayan chief there offered a group of women to him and his men. La Malinche was among those women.

Cortés decided to distribute the enslaved women as war prizes among his captains and La Malinche was awarded to Captain Alonzo Hernández Puertocarrero. She was described by conquistador Bernal Díaz Del Castillo as “pretty, engaging, and hardy.”

La Malinche showed an aptitude for language. She became proficient in Spanish and was already fluent in multiple native tongues, including Nahuatl, which the Aztecs spoke. She quickly distinguished herself from the other native slaves as a useful interpreter and the Spanish baptized her under the respectful name “Doña Marina.”

The Betrayals Of Doña Marina

Wikimedia CommonsA meeting between Cortés and Moctezuma II with La Malinche, a.k.a. Doña Marina, acting as their interpreter.

After Puertocarrero returned to Spain, Cortés took La Malinche back under his possession. She quickly became a crucial part of Cortés’ conquest of the powerful Aztec empire.

In correspondences to the Spanish monarch, Cortés mentioned La Malinche a couple of times in her role as an interpreter. She served as an indispensable translator and a strategic liaison between the Europeans and the natives, which was a remarkable feat given the norms of the time and her position as a slave.

“This slave woman broke the rules when she became a translator,” Sandra Cypess, professor emeritus of Latin American history at the University of Maryland, told NPR. “In the Catholic faith, women were not supposed to talk in public. And she talked. In Aztec culture, Moctezuma was the Aztec ruler, known also as Tlatoani, or ‘he who speaks.’ Only the powerful spoke.”

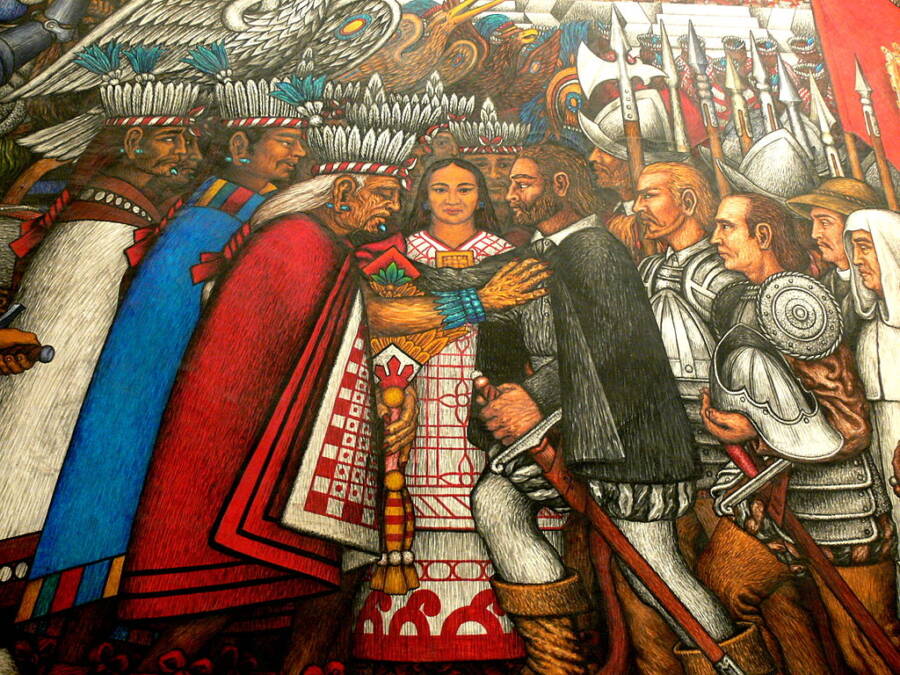

La Malinche further secured her position in the eyes of the Spanish by acting as their ally. She repeatedly saved Cortés and his men from Aztec attacks by gathering intel from locals. In one instance, La Malinche befriended an old woman who told her about a plot concocted by the Aztec king Moctezuma II to invade the Spaniards.

When La Malinche relayed this information to the conquistadors, Cortés made plans to evade the attack. La Malinche presented intelligence like this multiple times to the Spaniards, helping them to anticipate and thwart attacks by the Aztecs. The conquistadors’ deftness in avoiding the Aztecs fed the growing belief among many natives that the Spaniards had the support of mystical powers.

Wikimedia CommonsMany believe that the Spanish conquest of the Aztecs would not have been possible without La Malinche’s help.

La Malinche acted as more than Cortés’ strategist, however. She also gave birth to his child, a baby boy named Martín Cortés, who was among the first-known mestizos, or Spanish children born of mixed race.

Even though early historians regarded La Malinche as Cortés’ mistress or even his lover, there is little evidence to suggest that their relationship involved any love or intimacy. Indeed, La Malinche was originally one of Cortés’ slaves.

What isn’t disputable, however, is that in 1521, Cortés’ army invaded Tenochtitlan in the final siege that marked the decimation of the Aztec empire.

The Modern Controversy Over Malintzin

Wikimedia CommonsPortrait of La Malinche, also known as Malintzin.

During her time by Cortés’ side, La Malinche was, in part, respected by native tribes because of the influence that she wielded as the bridge between the Spaniards and indigenous people. Indeed, the Aztecs named her “Malintzin” which is the name “Malinche” with the honorary addendum, “tzin,” attached.

But over time her reputation changed for the worst. La Malinche’s negative depiction in literature and pop culture partly came from the influence of Catholicism, which painted her as the “Mexican Eve” (as in the biblical Adam and Eve) who was responsible for committing heinous sins against her own people.

To some modern Mexicans, La Malinche’s story is one of deep betrayal. The Mexican phrase malinchista is a popular insult used to describe someone who prefers a foreign culture over their own.

But La Malinche’s story is much more than this, at least according to some feminist Mexican writers who saw her as a symbol of strength, duality, and human complexity. Mexican writer Octavio Paz described La Malinche as both victim and traitor, writing:

“It is true that she gave herself voluntarily to the conquistador, but he forgot her as soon as her usefulness was over. Doña Marina becomes a figure representing the Indian women who were fascinated, violated, or seduced by the Spaniards. And as a small boy will not forgive his mother if she abandons him to search for his father, the Mexican people have not forgiven La Malinche for her betrayal.”

Wikimedia CommonsThis statue of Cortés, Malintzin, and their son Martín was moved because of the protests it sparked about Malintzin’s legacy as a traitor.

In contrast to her much-maligned reputation, many contemporary historians highlight the desperate circumstances in which La Malinche found herself and commend her for her resilience and self-preservation. Although she certainly played a considerable role in the fall of the Aztecs, as an indigenous slave stuck between two warring cultures she also may have had no other choice.

Perhaps author Marie Arana most aptly described La Malinche’s situation in her book Silver, Sword, and Stone: Three Crucibles in the Latin American Story, when she wrote, “She would be Cortés’ avatar, strategic advisor, and mother of his first child: in other words, a slave with extraordinary power.”

After this look at La Malinche or Malintzin, learn about this ancient Mayan palace that was found to contain human remains. Then, discover the horrifying history of the Trail of Tears, the U.S. government-sanctioned ethnic cleansing that removed 100,000 Native Americans from their ancestral lands.