Teenage lovers Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb thought they were smart enough to kidnap and murder 14-year-old Bobby Franks without getting caught — but within 10 days of the crime, they both confessed.

Chicago History Museum Nathan Leopold (middle) and Richard Loeb (right) with Judge John R. Caverly (left).

In 1924, Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb set out to commit the “perfect crime.” The teens thought they were clever enough to get away with murder, and they spent months plotting out their foolproof scheme. That May, Leopold and Loeb kidnapped and killed a 14-year-old boy named Bobby Franks.

At first, everything went as planned. They dumped Franks’ body, sent a ransom note, and sat back to watch the investigation unfold, confident that they would never be caught. Then, the police found Leopold’s eyeglasses alongside the boy’s remains.

Within 10 days, the teens had confessed to everything. Their “trial of the century” began in July, and because their families hired the famed attorney Clarence Darrow to represent them, they both avoided the death penalty and were sentenced to life in prison instead.

Their once-promising futures quickly crumbled in front of them. Richard Loeb was killed by a fellow inmate 12 years later; Nathan Leopold spent 34 years behind bars before he was released on parole in 1958.

So, what exactly compelled two bright young men with every opportunity in the world to throw it all away?

The Fateful Meeting Of Nathan Leopold And Richard Loeb

Nathan Leopold was born in Chicago in 1904. His father was the president of the Manitou Steamship Company and the owner of a paper mill in Morris, Illinois.

Leopold grew up in Kenwood, an affluent suburb of Chicago. He was a brilliant child who started college when he was just 15. He also spoke several languages fluently and had published two papers in America’s leading ornithological journal by the time he was 19.

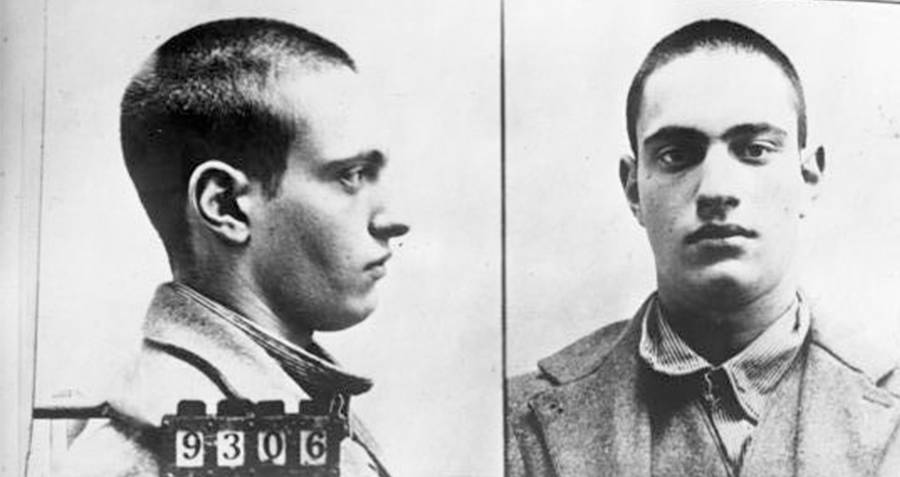

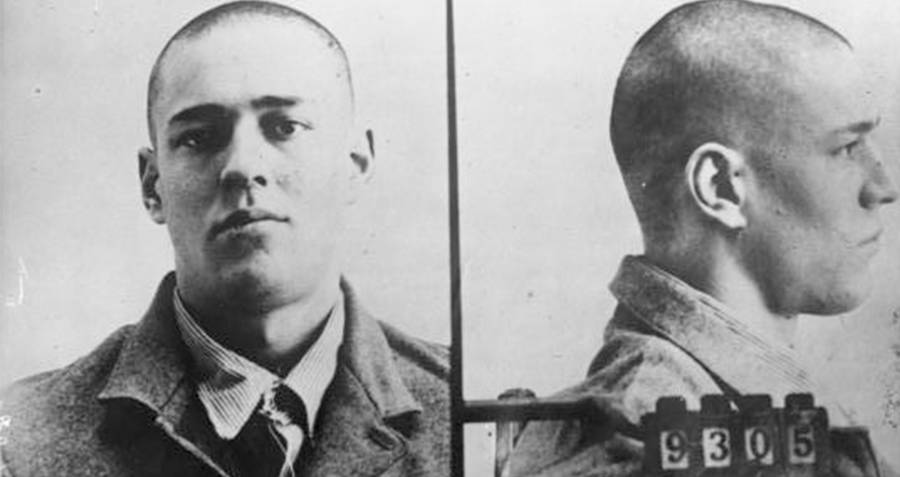

Wikimedia CommonsNathan Leopold’s mugshot.

Richard Loeb shared a similar background. He grew up in the same suburb of Chicago and attended the University of Michigan, becoming the school’s youngest graduate at only 17 years old.

The two first met in 1920, but they became close friends three years later while Leopold was studying at the University of Chicago and Loeb was taking graduate courses at the school. Their relationship soon turned sexual.

Wikimedia CommonsRichard Loeb’s mugshot.

Leopold was interested in psychology, particularly the concept of Übermenschen (“supermen”) put forth by German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche. Nietzsche suggested that there were certain members of society with superior intellect who were able to rise above the laws that were meant for ordinary people.

Soon, Leopold became convinced that he was one of these supermen and, as such, was not bound by the laws or ethics of society. Eventually, he convinced Loeb that he was one, too.

In order to test their perceived immunity, the two began committing petty theft. They broke into a fraternity house at the University of Michigan to steal a typewriter. When that got no attention in the press, the duo moved on to arson.

When that, too, was ignored by the media, Leopold and Loeb decided they needed a larger crime, a perfect crime, one that would gain national attention. One that would ultimately prove deadly for 14-year-old Bobby Franks.

The Abduction And Murder Of Bobby Franks

At the end of 1923, Leopold and Loeb started planning their “perfect crime.” They decided murder would garner the most attention, so they began plotting how they would get away with it. They chose a weapon, decided how they would dispose of the body, and drafted a ransom note. All they needed was a victim.

On May 21, 1924, 19-year-old Leopold and 18-year-old Loeb drove around the streets of Kenwood, searching for the final piece of their macabre puzzle. When they spotted Loeb’s cousin, Bobby Franks, walking along the road, they knew they’d found their victim. Franks’ father was the president of a watch company and would easily be able to pay the ransom Leopold and Loeb were demanding.

The teens lured Franks into their car under the guise of asking him about his new tennis racket. Franks sat in the front seat next to Leopold, who was driving. From the back seat, Loeb chatted with the boy — and then bashed him on the head with a chisel when he turned to look out the window.

Wikimedia CommonsBobby Franks, left, with his father.

Loeb brought the chisel down four times, but Franks was still alive. Blood spurted through the car as Loeb pulled the boy into the back seat and shoved a rag down his throat to suffocate him. Meanwhile, Leopold drove to the South Side of the city. Bobby Franks was long dead by the time they stuffed him into a culvert near some railroad tracks.

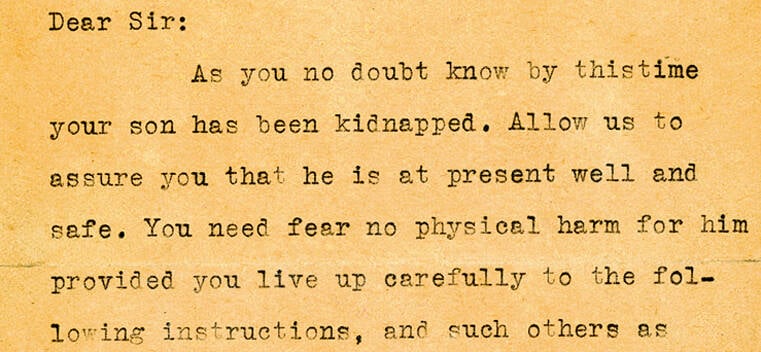

They then drove home as if nothing had happened. Leopold dropped a ransom note demanding $10,000 into a mailbox, and the teens destroyed the typewriter they’d used to write it and dumped it into Jackson Park Lagoon.

Before Franks’ family could pay the ransom, however, the boy’s body was found. The very next morning, May 22, a man spotted the corpse as he was walking home from work. Leopold and Loeb’s perfect crime was already unraveling. Still, the murder became the talk of the town, and the killers basked in the attention their crime was receiving.

Then, investigators found a pair of eyeglasses at the scene.

The Undoing Of Leopold And Loeb’s ‘Perfect Crime’

Once the police discovered the glasses, it was game over for Leopold and Loeb.

Investigators were able to trace the frames, which featured a unique hinge, back to an optometrist in Chicago. The eye doctor told the police that he had only sold that particular style of glasses to three people — including Nathan Leopold.

The police brought Leopold in for questioning, and at first, he claimed that he’d likely dropped the glasses during a recent birdwatching trip. However, when detectives interrogated Loeb as well, their story started to fall apart. By May 31 — just 10 days after the murder — both men had confessed. Still, each of them insisted that the other was the actual killer.

Public DomainPart of the ransom note sent to Bobby Franks’ father.

Leopold and Loeb also both admitted that their motive had simply been curiosity and thrill. As reported by TIME, Leopold later said, “A thirst for knowledge is highly commendable, no matter what extreme pain or injury it may inflict upon others.”

With the confessions secured, prosecutors decided to seek the death penalty against Leopold and Loeb.

Inside The ‘Trial Of The Century’

The trial that ensued drew the attention of the country, and newspapers dubbed it the “Trial of the Century.” Leopold and Loeb’s families hired renowned defense attorney Clarence Darrow, who was known for his opposition to capital punishment.

During the month-long trial — which was actually a sentencing hearing given that both men had confessed and entered guilty pleas — Darrow famously gave a 12-hour closing argument begging the judge not to execute Leopold and Loeb. The speech has been hailed as the finest of his long career.

Chicago History MuseumLeopold, Loeb, and their attorney, Clarence Darrow, during their trial.

The trial included over 100 witnesses, including psychiatrists attesting to the criminals’ developmental abnormalities and trauma. According to Leopold’s defense team, the teen’s governess had sexually abused him when he was a child. In Loeb’s defense, the team brought up parental neglect as a factor in the young man’s violent behavior.

Ultimately, Darrow was successful. On Sept. 10, 1924, the judge sentenced Leopold and Loeb to life in prison, plus 99 years, to be served immediately. He cited the teens’ age as the reason for not handing over a death sentence.

With that, Leopold and Loeb were sent to Joliet Prison in Illinois to begin their life behind bars.

The Death Of Richard Loeb And The Fate Of Nathan Leopold

A year into his sentence, Nathan Leopold was transferred to the Stateville Penitentiary for an emergency surgery. Loeb was moved to the same facility five years later. There, the duo worked together to add courses to the prison’s school system.

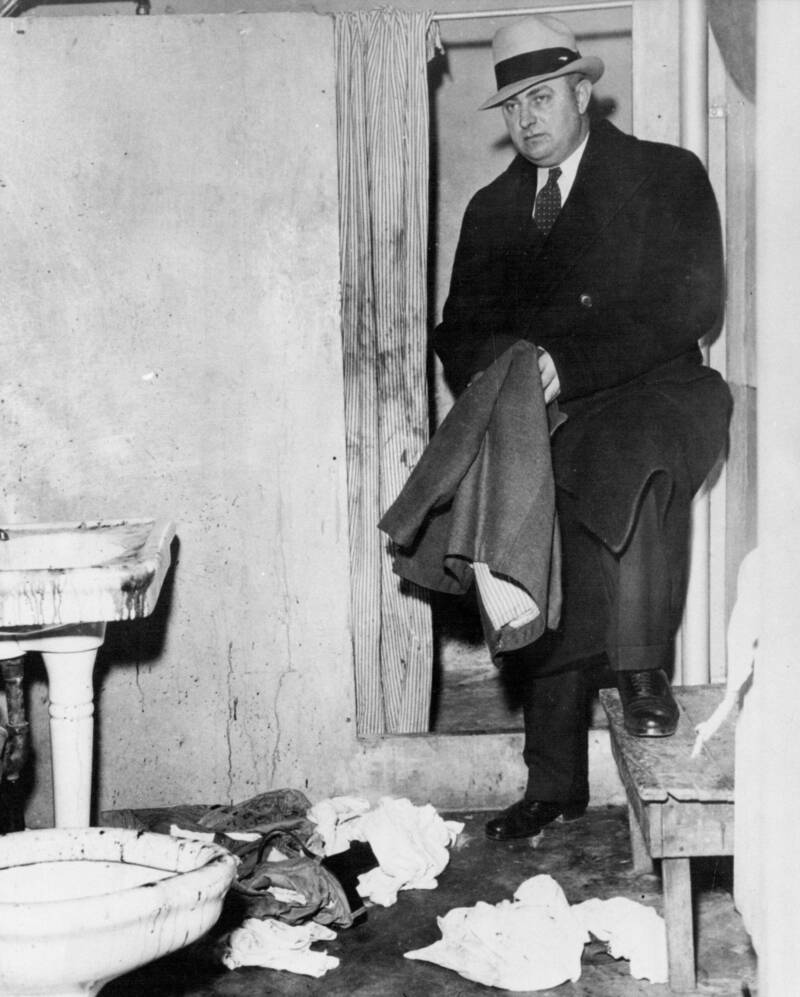

Then, on Jan. 28, 1936, an inmate named James Day attacked Loeb with a straight razor in the shower room, killing him. Loeb was 30 years old. Day claimed that Loeb had sexually propositioned him, and he was ultimately found not guilty of murder.

SuperStock / Alamy Stock PhotoWarden Joseph E. Ragen of Stateville Penitentiary views the room where Richard Loeb was fatally slashed by fellow convict James Day.

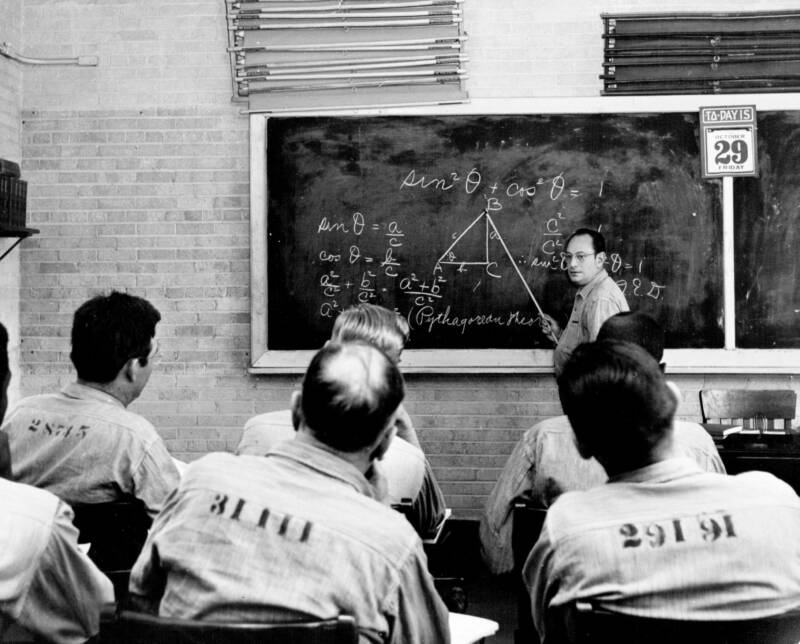

After his friend’s death, Leopold reportedly suffered from intense bouts of depression. He managed his mental health struggles by pouring his efforts into improving educational opportunities at the facility. He taught classes and took on new roles, such as organizing the library and volunteering at the prison hospital.

Because of his good behavior, Nathan Leopold was released on parole in March 1958. He wrote an autobiography titled Life Plus 99 Years and used the proceeds to start a foundation for emotionally disturbed youth. He later moved to Puerto Rico, earned a master’s degree in social work, and published a book on the island’s native bird species. He even got married in 1961.

SuperStock / Alamy Stock PhotoNathan Leopold teaching trigonometry in prison. 1955.

Leopold lived out the rest of his days in Puerto Rico. He died from a heart attack in 1971 at the age of 66.

In his autobiography, Leopold reflected on his and Loeb’s “perfect crime,” writing:

“Looking back from the vantage point of today, I cannot understand how my mind worked then. For I can recall no feeling then of remorse. Remorse did not come until later, much later. It did not begin to develop until I had been in prison for several years; it did not reach its full flood for perhaps 10 years. Since then, for the past quarter century, remorse has been my constant companion. It is never out of my mind. Sometimes it overwhelms me completely, to the extent that I cannot think of anything else.”

After learning about Leopold and Loeb, read the story of Rodney Alcala, the Dating Game Killer. Then, go inside the chilling crimes of the Chicago Strangler.