Many diseases have been around as long as humans, but Leprosy’s social history is the most inextricably linked with human evolution.

A portrait of an elderly blind woman at the Nuang Kan Leper Colony in Kengtung, Myanmar.

A plague to rule them all, leprosy is very likely the oldest infectious disease in human history. Written accounts of the disease — sometimes referred to as Hansen’s Disease—date as far back as 600 B.C., and the genetic evidence alone supports the existence of Leprosy infections in 100,000-year-old remains.

While many other human diseases have been around as long as human beings have–such as nutritional night blindness, tuberculosis and of course sexually transmitted infections (syphilis)–Leprosy’s social history is the one that is most inextricably linked with human evolution.

Source: Giphy

During the Neolithic period, human life and social behavior underwent a major change: instead of the freewheeling hunter-gatherer lifestyle that had dominated human history, humans began forming close-knit communities around agriculture. Living in such close quarters for the first time, many zoonotic diseases–diseases that can be transferred from animals to humans–began appearing in humans, Leprosy included.

Source: Giphy

As humans evolved, the bacterium responsible for the infection underwent a peculiarly slow parasitic evolution. Through reductive evolution, the bacterium lost as much as 40 percent of its genes, meaning that those genes were rendered non-functioning pseudogenes. As one scientist said, Leprosy is sort of a wimpy pathogen: outside the host, the bacterium will die within just a few hours and it can be cured completely through a cocktail of powerful drugs. In other words, it wasn’t the infection itself that gave Leprosy its reputation, but its social stigma throughout the course of history.

Source: Miller Sport

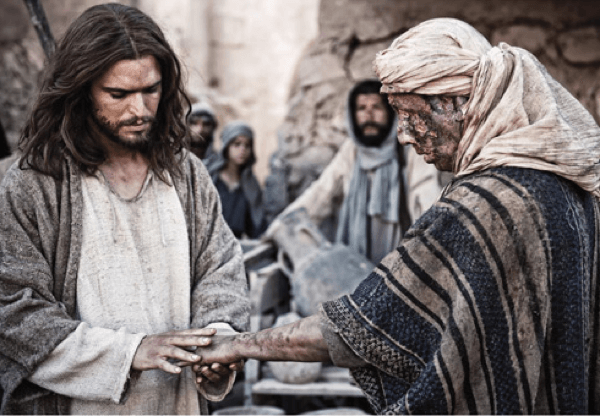

As a cultural phenomenon, Leprosy appears in biblical parables, has been passed down through written and oral tradition for millennia and immortalized via images from 20th-century leper colonies. While “leper bells” were often thought of as a warning, the chimes worn by lepers were not meant to repel but help them receive alms since they often had hoarse voices, or had lost the ability to speak entirely.

Painful and even terrifying disfigurement, missing limbs and dense scarring were the consequences of contracting Leprosy before treatments were developed. During a period in the mid-1960s, when the bacteria became resistant to treatment (dapsone, which had been developed in the 1940s), fear of lepers resurfaced, at which point two more drugs were developed and added to the multi-drug therapy that is still used today to treat the disease. Though cases of Leprosy have greatly diminished in the years since MDT became widely disseminated (for free) by the WHO, the stigma has remained.

Life on a Leper Colony

While there are currently no active Leprosy cases on the island of Kalaupapa, Hawaii, many Leprosy patients who arrived there (between 1866 and 1969, when it was an active leper colony) chose to live out the rest of their lives away from the general populace. Even if they were cured and posed no risk to population health, their socially-produced shame — paired with the physical scars they bore— has kept them isolated.

One contemporary leper, who was diagnosed in 1968, made a pointed effort to confront the stigmatization of the disease head-on. In his memoir, Squint: My Journey with Leprosy, José P. Ramirez, Jr. recounts his experience of being forcibly quarantined for seven years after he was diagnosed with Leprosy in his early twenties. His years spent in the leprosarium gave him keen insight into the world’s persistent misunderstanding of the disease, its mechanism of infection, and the realities of living a normal life once one is cured.

Leprosy’s Magical Act

Through what scientists have termed “biological alchemy”, Leprosy bacterium is able to turn body cells — particularly nerve and skin cells, which the disease targets— into stem cells that can be used in any part of the body to transmit the infection. While the bacterium itself might be microbiologically “wimpy”, it’s evolutionarily clever, and scientists now believe that’s why it still infects humans today.

Another reason is that Leprosy is no longer a human-only infection: while previously there had only been isolated infections in other mammals, most often chimpanzees or gorillas, it’s now widely known that Leprosy is indigenous to North America not through humans, but armadillos.

Source: Giphy

Armadillos (which were called āyōtōchtli or “turtle-rabbits” by the Aztecs) are in the same family as anteaters and sloths and are similarly adept at eating fire ants, which makes them a welcomed part of the biosphere. However, Leprosy appears to occur naturally in them, and through human contact, they are capable of transmitting the bacteria to a human host.

It’s been determined that other than genetic susceptibility (which is also present in humans, though 90 percent of us are actually immune to it) armadillos are prone to contracting Leprosy because they maintain a very low body temperature in which the bacterium can thrive. Since Leprosy was unknown in the New World prior to Europeans’ arrival, at some point several hundred years ago early European settlers introduced Leprosy to armadillos.

It’s not that much of a stretch when you consider that the incubation period for Leprosy is, on average, around five years. It’s easy enough to contract and spread without knowing that you have it: additionally, symptoms may not crop up for as many as twenty years after you’ve been infected. In modern times, with the advent of MDT and overall a higher standard of sanitary conditions, Leprosy is not only relatively rare, but also highly curable.

Of course, if you require a reason to avoid armadillos, citing Leprosy is valid.