Lilias Adie was accused of having had sex with Satan and terribly mistreated in prison. Those who abused her were so afraid she would "reanimate" that they buried her under a large slab of stone. Her remains are missing to this day.

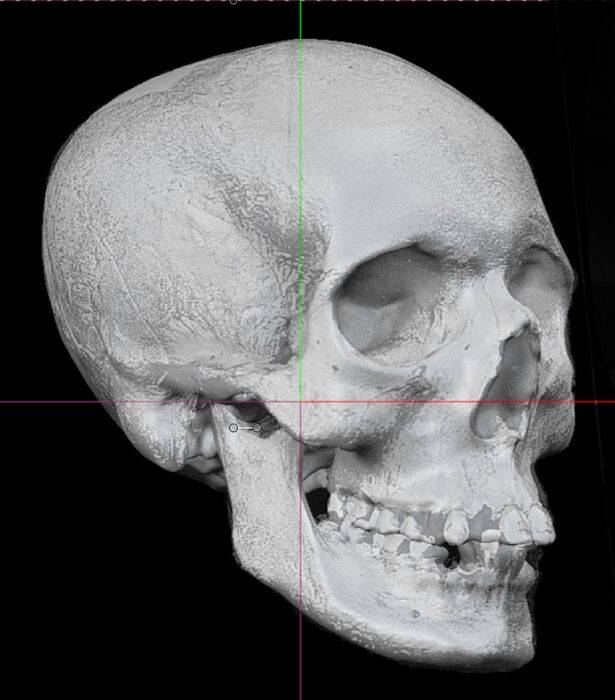

University of DundeeLilias Adie was in her late 50s or early 60s when she committed suicide. In the late 19th century, parts of her coffin were turned into walking sticks, one of which was gifted to Andrew Carnegie.

According to records from the Fife Council, approximately 3,500 women were executed as witches in Scotland between 1560 and 1727 — with some estimates reaching as high as 6,000. Lilias Adie died from suicide in prison in 1704 before she could be strangled and burned at the stake, according to CNN.

It’s believed that her confessions of being a witch and having had sex with the devil were coerced. Though she killed herself before the government could, her corpse was nonetheless burned at the stake before being buried on a beach in Torryburn, Fife in Scotland.

The locals were so terrified that she might “reanimate” from the dead that they buried her under a hefty slab of stone. Resourceful curio hunters still managed to rob the remains in 1852, however, with her skull finding its way to St. Andrew’s University Museum in 1904.

After the university photographed her skull that same year, all known remains of Lilias Adie went missing.

Dundee University recently used the century-old photos to digitally reconstruct Adie’s face, giving us a glimpse of the only known Scottish “witch” in history.

PAJoseph Neil Paton instructed curio hunters to steal Adie’s remains in 1852.

“It’s important to recognize that Lilias Adie and the thousands of other men and women accused of witchcraft in early modern Scotland were not the evil people history has portrayed them to be,” said the leader of this cultural campaign and Fife Council councilor Julie Ford. “They were the innocent victims of unenlightened times.”

“It’s time we recognized the injustices served upon them. I hope by raising the profile of Lilias we can find her missing remains and give them the dignified rest they deserve.”

Fife Council archaeologist Douglas Speirs said that the “short-lived witch-hunting craze” in Fife resulted from a local illness that led to the misguided arrests of residents like Adie. She was “treated roughly” as a prisoner: continuously interrogated, deprived of sleep, and coerced into a confession.

Adie was in her late 50s or early 60s when she committed suicide. Whether to evade death by strangulation or to die by her own hands as the last refuge for dignity, Adie’s story is one of thousands that are reminding many of the paranoia-induced frenzy of the time.

“It’s time to move the narrative away from the Halloween-style figure of the fun witch, and recognize the historic gender bias and suffering that women were exposed to in the name of witch-hunting,” said Speirs.

Speirs explained that tracking down Adie’s remains is merely one the campaign’s missions and that the overarching goal here its to raise awareness of how persecuted women really were during this historical period.

University of DundeeAdie’s remains were robbed in 1852 and eventually found their way to St. Andrew’s University before disappearing. The last sighting of her skull was at the Empire Exhibition in Glasgow in 1938.

According to The National, a ceremony at Lilias Adie’s grave is scheduled for Saturday while the quest for her remains continues. A Witches Memorial Trail is also in the process of being proposed for West Fife’s coast.

The last sighting of Adie’s skull after being photographed in 1904 was reportedly at the Empire Exhibition in 1938 in Bellahouston in Glasgow. Her stringent burial was directly tied to her mistreatment as a prisoner — as those who were responsible believed she would come back to haunt them.

“The idea of returning from the grave was a very old one and a key feature of witchcraft belief was that if someone died having given power to Satan he could reanimate you after your death,” said Speirs.

Reanimated bodies were described by medieval historians as “revenants,” from the Latin “reveniens” (returning) and the French verb “revenir” (to come back).

“Fearing the potential of revenant they buried her hastily and unceremoniously out on the foreshore which was traditionally reserved for those who died out of God’s grace,” said Speirs.

“They locked her in a wooden box rather than a coffin and for good measure put a half-ton slab on top of her to stop her rising out. It’s a gut churningly, sickening story — you can’t help being moved by it.”

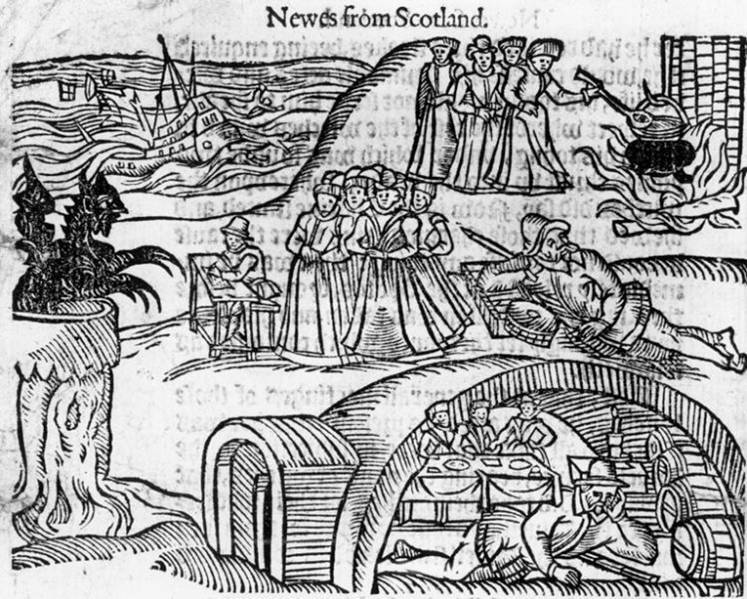

Wikimedia CommonsAn illustration of Scotland’s North Berwick witches, which are shown meeting Satan in the local churchyard. Witchcraft paranoia led to thousands of executions across a 200-year period. From the contemporary pamphlet ‘Newes From Scotland.’ 1590.

It was Speirs himself who rediscovered Lilias Adie’s grave in 2014, which had been robbed over a century earlier on instructions from antiquarian Joseph Neil Paton. Paton was a believer in phrenology and thought there was much to learn from Adie’s skull.

After her remains were handed to the Fife Medical Association, it found its way to the University of St. Andrew, while parts of Adie’s coffin were turned into walking sticks as souvenirs. One of those sticks was given to Andrew Carnegie by Robert Baxter Brimer who had helped dig up Adie’s grave in 1852.

Speirs was introduced to Adie’s story in 2014 by historian Dr. Louise Yeoman and after discovering her grave, he’s desperately been searching for her remains.

“I’ve written to various collections in Scotland but so far not been able to find them,” he said in reference to Adie’s skull and bones.

“The really stunning thing about Adie’s case is that it happened in 1704, the Enlightenment century and century of achievement. It’s a horrible reminder of the degree to which there was still a very strong belief in witchcraft.”

Councillor Kate Stewart — who’s largely responsible for the big push in raising awareness of Adie’s case — was adamant that the upcoming memorial aims to honor every single woman who suffered from Scotland’s witch-hunting craze — and not just one person.

“We are wanting a memorial not just for her but for everybody who perished after being accused of being a witch,” she said. “There is no recognition that these people were killed for nothing. When you did down its was a horrible, horrible time for ordinary folk, particularly women. The suffering was horrendous and we should recognize that wrong was done and remember them in a respectful way.”

After learning about the missing remains of Lilias Adie and Scotland’s dark past of witchhunting, read about the historical origins of the witch. Then, learn about the worst witch trial in history.