Louisa May Alcott infused Little Women with her personal trials and tribulations of growing up in an impoverished and unconventional family.

Louisa May Alcott’s most famous work follows the tale of four young women trying to make their way in the world. Her complex, realistic characters — sisters Meg, Beth, Jo, And Amy — were actually derived from Alcott’s own experiences with her own three sisters.

Alcott endured all the tribulations of a progressive 19th-century woman, but she managed to transform these struggles into something lovely: the captivating and enduring story of Little Women.

Too bad she hated it.

Louisa May Alcott’s Unusual Childhood

Wikimedia CommonsThough money poor, the Alcott family was not impoverished in spirit and tolerance as their home was a stop on the Underground Railroad.

Before she became one of the most prominent female American writers of the 19th century, Louisa May Alcott was the daughter of a progressive but poor family.

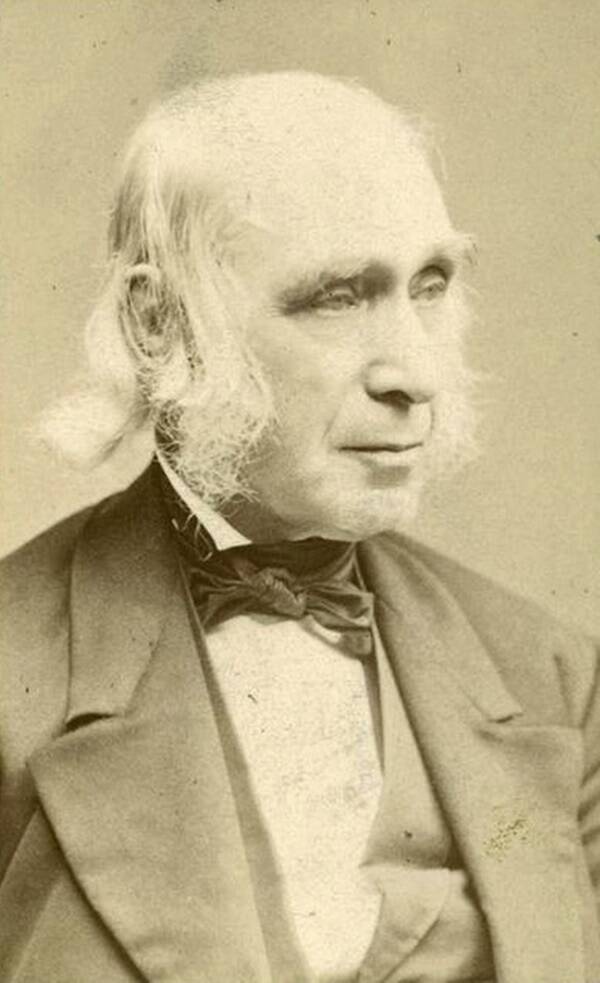

Her mother, Abigail “Abba” May, came from a line of distinguished war heroes. Her father, Amos Bronson Alcott, was the son of a farmer yet he was very well-read and became a self-taught educator.

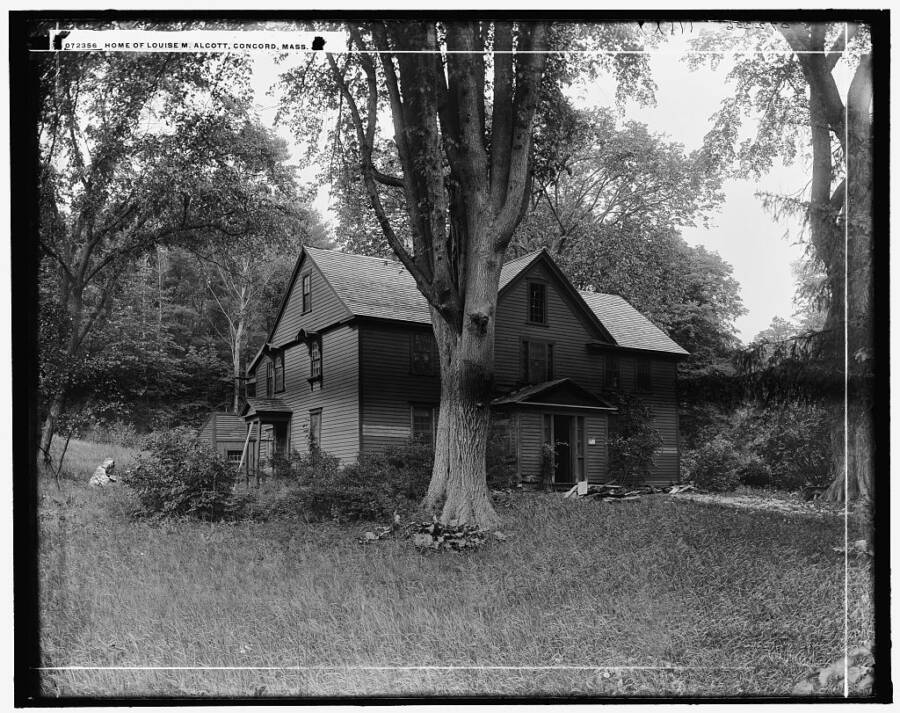

Louisa May Alcott was born on Nov. 29, 1832, in Germantown, Pennsylvania but she grew up in Concord, Massachusetts most of her life. Even as a toddler, Louisa May Alcott was described as strong-willed and stubborn, traits she inherited from her mother, to whom she looked up and with whom she was close.

Wikimedia CommonsHer father, Amos Bronson Alcott, was a progressive educator and member of the transcendentalism movement.

Alcott was the second-born of four daughters. She was incredibly close with her sisters: Anna (the eldest), Lizzie, and May (the youngest). While Alcott’s bonds with the women in her family were unwavering, her relationship with her father, Amos, was complicated.

Amos was a transcendentalist, a philosophy that encouraged self-reliance, imagination, and creativity, yet he was also a stickler for denial and control. He employed his experimental methods in childcare onto his own daughters, putting them on strict hourly schedules and depriving them of adolescent indulgences like sitting on their mother’s lap or sleeping with the light on. Alcott herself was often forced to give up her sweet treats to other children as a way of practicing the “sweetness of self-denial.”

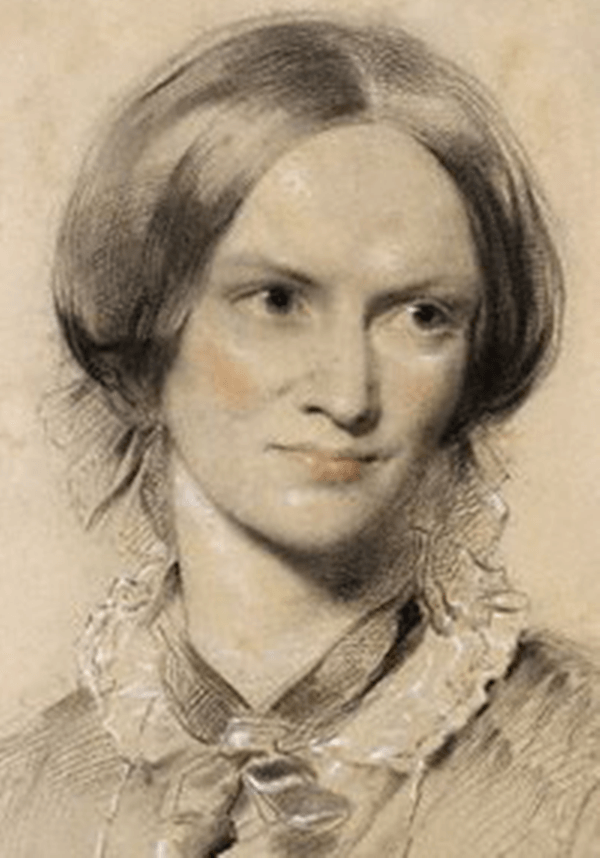

“Wonder if I shall ever be famous enough for people to care to read my story and struggles. I can’t be a [Charlotte Brontë], but I may do a little something yet.”

Her father’s involvement in the transcendentalist movement distracted him from providing for his family, so the women — including Alcott herself — were forced to take on the roles of breadwinners. The family’s financial woes caused Alcott to miss school regularly and take on odd jobs to make ends meet. The only solace she found during these hardships was in writing.

Library of CongressWhen she was two, the family relocated to Boston, Massachusetts, where Louisa May Alcott spent most of her life.

In 1843, when Alcott was 11, Amos moved the family into an experimental community with other transcendentalists. The members inhabited a plot of land they bought dubbed Fruitlands, which was meant as a self-sustaining Utopian society. Members committed themselves to a vegetarian diet and manual labor without enslaved animals.

It was a peculiar setting for a teenage girl to grow up in but her father’s radical philosophies also put her in close circles with the greatest minds of the time. She received excellent tutelage from her father’s like-minded colleagues like Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Margaret Fuller, and Julia Ward Howe.

The social experiment of Fruitlands failed but it at least gave Louisa May Alcott fodder for her writing. One of her earlier works, entitled Transcendental Wild Oats, was a satirical comedy based on her time living among the transcendentalists.

It would be one of the many stories she wrote based on the peculiar happenings in her own life.

In 1850, the Alcotts opened their home up to fugitive slaves as a stop on the Underground Railroad. Her father founded an abolitionist society in their hometown that year and instilled his abolitionist views in his daughters.

Louise May Alcott herself would grow up to be a progressive patriot, joining the Civil War effort for the Union as a nurse. “My greatest pride,” Alcott wrote of her role in the Civil War, “is that I lived to know the brave men and women who did so much for the cause and that I had a very small share in the war which put an end to a great wrong.”

Louisa May Alcott’s Written Works

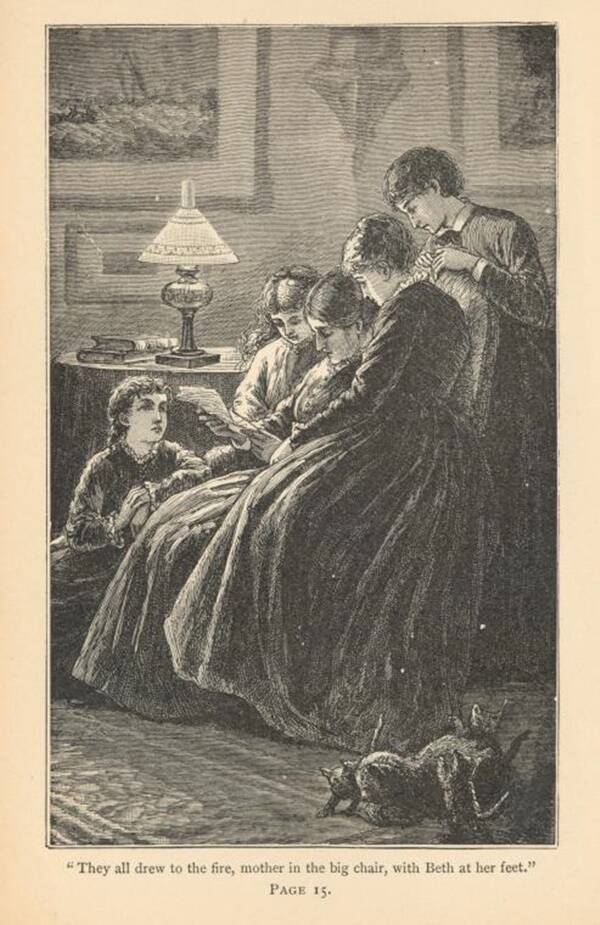

Wikimedia CommonsAn illustrated page from her most popular book Little Women.

Poverty weighed heavily on the young writer during her teenage years, perhaps more so as she was one of the elder daughters. According to Elaine Showalter in the introduction to Alternative Alcott, a collection of Alcott’s “sensation tales,” Alcott vowed to bring her family out of poverty:

“I will do something by-and-by. Don’t care what, teach sew, act, write, anything to help the family; and I’ll be rich and famous and happy before I die, see if I won’t!”

Alcott stuck to her word. At 16 she became a teacher — like her father — to make more money. But she did not care for scholarship; her true passion lay in writing. Yet an abundance of house chores and a day job left the budding writer little time to read or write.

Wikimedia CommonsLouisa May Alcott shared many similarities with her literary idol, Charlotte Brontë, including the unfortunate fate of a difficult upbringing.

Alcott finally managed to publish her own collection of short fairytales titled Flower Fables in 1854. Alcott had a great admiration for Emerson, whose daughter, Ellen, she dedicated the book to. Despite her literary accomplishment, life was otherwise so difficult for the 24-year-old that she had even contemplated committing suicide.

Alcott had walked to the Charles River and considered throwing herself into it, but she decided that she would instead “take Fate by the throat and shake a living out of her.”

Alcott deeply admired Charlotte Brontë, another prolific female writer from the early 19th century. She found renewed strength in the writer’s biography which featured struggles so closely reminiscent of her own that by 1860, Alcott began contributing regularly to the Atlantic Monthly for payment.

Most of this earlier writing was published under the gender-ambiguous pseudonym A.M. Barnard as publishers and readers still harbored unfair bias against female writers.

Louisa May Alcott’s Orchard HousePortrait of Elizabeth Sewall Alcott, or “Lizzie” as Louisa May called her, who died of scarlet fever.

She naturally found regular material for her writing from her own messy life. In her essay, How I Went Out Of Service which was published in The Independent, Alcott recounted her denigrating job as a domestic servant in which her employer made romantic advances towards her and bogged her in the dirtiest chores when she rejected him.

Her novel Hospital Sketches was inspired by her time as a Union hospital nurse during which she contracted typhoid fever and health problems that plagued her for the rest of her life.

Even in her most-read work, Little Women, painful remnants of Alcott’s past are scattered throughout.

The True Story Behind Little Women

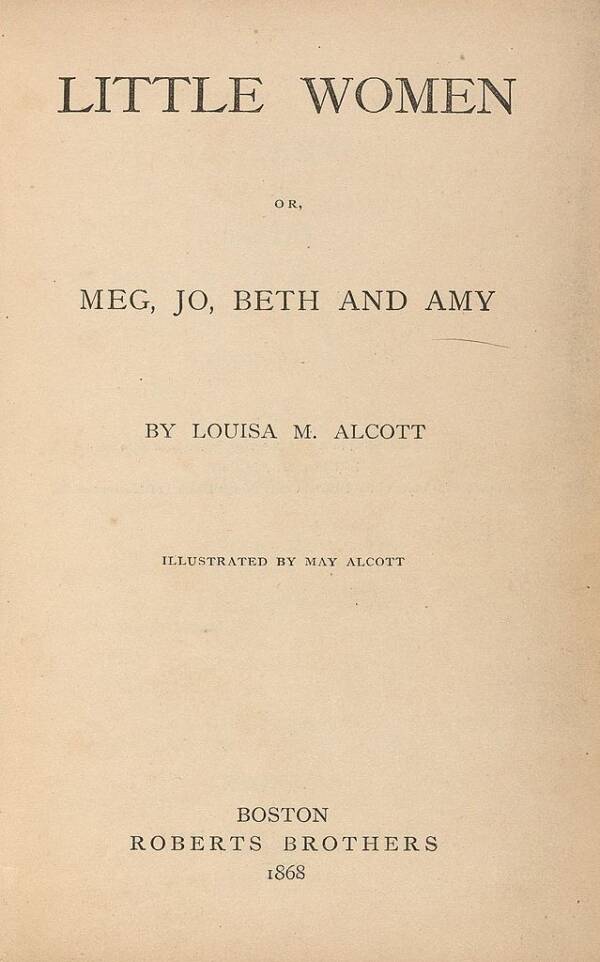

Wikimedia CommonsAn original copy of Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women which is now over a century old.

Alcott’s atypical upbringing and tight-knit relationships with her sisters later inspired her most recognized work, Little Women, which follows the story of the four March sisters — Meg, Jo, Beth, and Amy.

The parallels between Alcott’s family of vibrant women and the March sisters aren’t uncanny, they’re intentional. The eldest sister in the book, Meg, was modeled on Alcott’s own oldest sister, Anna; Beth was based off her real sister Lizzie; Amy was the caricature of her youngest sister, May; and Jo was modeled after herself.

“I don’t miss [Lizzie] as I expected to do, for she seems nearer and dearer than before; and I am glad to know she is safe from pain and age in some world where her innocent soul must be happy.”

It seems the book may also have been a sort of catharsis for Alcott, considering she wrote the whole manuscript in less than three months and featured real-life traumas in the book, like the death of her sister Lizzie by scarlet fever. Alcott also honestly portrayed her sibling rivalry between her youngest sister, May, through the rivalry between characters Jo and Amy.

Little Women was initially published as a short story series and became an instant hit among young female readers after its first installment in 1868. The story was later published in the form of a novel and its popularity cemented Alcott as a bonafide author. More importantly, the profits helped her to provide for her family.

“Money is the end and aim of my mercenary existence,” she once wrote to a friend.

Indeed, Alcott wrote the female-focused story at the behest of her publishers, but Alcott herself was never interested in writing a book for girls. “I don’t enjoy this sort of thing,” Alcott admitted in her diary. “Never liked girls or knew many, except my sisters; but our queer plays and experiences may prove interesting, though I doubt it.”

She thought this kind of writing for girls to be “moral pap for the young.”

IMDBLittle Women has been adapted for film and television various times. The original book was released in shorts as a part of a larger series.

In her journals and her letters to friends, Alcott wrote plainly about her resentment for the popularity of Little Women. She especially disliked the demand from its young female fans who wanted Jo’s character to marry Laurie, the March sisters’ handsome and rich next-door neighbor.

For Louisa May Alcott, who watched her mother endure a poor marriage, eternal singledom or “spinsterhood” was a far better fate than becoming a wife.

“Girls write to ask who the little women marry, as if that were the only end and aim to a woman’s life,” she wrote in her journal while finishing the second half of Little Women. “I won’t marry Jo to Laurie to please anyone.”

She felt the same about herself. Alcott never did wed or have any children. “I’d rather be a free spinster and paddle my own canoe,” she wrote.

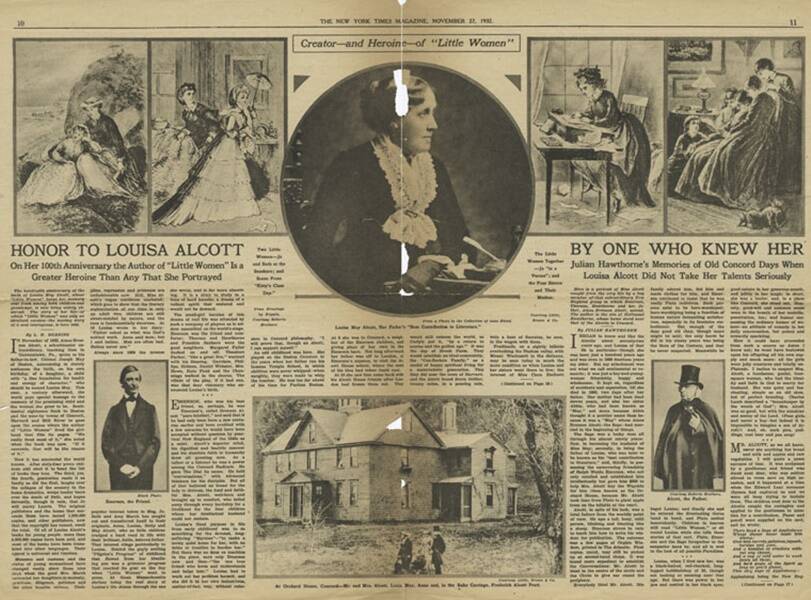

The New York Public LibraryA newsprint covering 100 years since Louisa May Alcott’s writing was published.

Still, Alcott did not want to disappoint her readers who had obviously become overly invested in her characters. As a cheeky compromise, in the Little Women sequel titled Good Wives, the author married Jo off but to someone else other than Laurie.

The story of Jo March and her sisters was so embraced by readers that Alcott was compelled to write more installments to the series. She published Little Men (1871), which detailed Jo March’s life at the Plumfield School that she founded with her husband Professor Bhaer, and Jo’s Boys (1886) which was the final chapter to the March family saga.

A Tale That Endures

Louisa May Alcott was also a progressive feminist. She was in many ways ahead of her time. She possessed an independence and sense of freedom which she felt belonged to all women. In 1879, she became the first woman registered to vote in Concord, Massachusetts.

In 1888, after years of struggling with illness, Louisa May Alcott took her last breath at 56. But Little Women didn’t die with its author.

Wilson Webb/CTMG/IMDBGreta Gerwig directed the 2019 adaptation of Louisa May Alcott’s enduring story.

In 1912, Marian de Forest adapted Little Women for Broadway. It was adapted into a silent film a few years later. There were also, of course, multiple big-screen productions of Little Women in color, including the 1994 adaptation starring A-listers Kirsten Dunst as Amy March and Winona Ryder as Jo.

Producer Denise Di Novi, who was behind the 1994 production, teamed up with actor-turned-director Greta Gerwig of Ladybird in the newest take of the classic story set to premiere Christmas 2019.

The March girls were “four really talented weirdo girls who were ambitious and funny and competitive and kind of crazy,” said Gerwig in a New York Times interview. It is perhaps why the story still resonates with women to this day.

Gerwig added that Alcott made “all of these inappropriate emotions for young women to have” so relatable and real that the story has remained relevant even today. The warmth and honesty between the March sisters and their disparate, independent characters are perhaps the reason why Little Women has been retold so many times since it was first published over a century ago.

Now that you’ve learned about Louisa May Alcott, the brilliant mind behind ‘Little Women,’ meet Emma Lazarus, the courageous Jewish poet behind the poem inscribed on the Statue of Liberty. Then, read about the little-known life of Ada Lovelace, the female engineer who created the first computer code.