For better food, a separate room, and protection from hard labor and the gas chamber, some prisoners became kapos — but they had to beat their fellow inmates in return.

In 1945, months after being freed from a Nazi concentration camp, Eliezer Gruenbaum was walking down the streets of Paris.

Born to a Zionist father from Poland, Gruenbaum was now staunch communist; he was planning to meet with a Spaniard at a local café to discuss the new communist regime in Poland. But before he could, someone stopped him on the street.

“Arrest him! Arrest him! Here’s the murderer from Auschwitz!” said one man. “It’s him — the monster from Block 9 at Auschwitz!” said another.

Gruenbaum protested. “Leave me alone! You’re mistaken!” he cried. But the police issued a warrant for his arrest the next day.

Gruenbaum was accused of one of the worst possible crimes a Jew in 1940s Europe could commit: being a kapo.

Coming from the German or Italian words for “head,” kapos were Jewish inmates that had accepted a deal with the devil.

In exchange for better food and clothing, increased autonomy, possible occasional visits to a brothel, and a 10 times greater chance of survival, kapos served as the first line of discipline and regulation within the camps.

They supervised their fellow inmates, oversaw their slave labor, and often punished them for the slightest infractions — sometimes by beating them to death.

In 2019, the Jewish Chronicle called the word kapo the “worst insult a Jew can give another Jew.”

At times, kapos were all that allowed the camps to continue operating.

Kapos: Perverse Products Of A Sadistic System

U.S. Holocaust Memorial MuseumA prosecution witness points out defendant Emil Erwin Mahl during the Dachau war crimes trial. Mahl was convicted of war crimes he committed as a kapo, including obeying SS officers and tying nooses around prisoners’ necks.

Under a system devised by Theodor Eicke, a brigadier general in the SS, kapos were the Nazis’ way of keeping costs down and outsourcing some of their least desirable work. The underlying threat of violence from both the SS above them and angry prisoners below brought out the worst in the kapos, and thus the Nazis found a way to get their inmates to torture each other for free.

Being a kapo came with small rewards that came and went depending on how well you did your job. That job, though, was preventing starving people from escaping, separating families, beating people bloody for minor infractions, moving your fellow prisoners into the gas chambers – and taking their bodies out.

You always had an SS officer breathing down your neck, ensuring you did your job with sufficient cruelty.

That cruelty was all that would save kapo prisoners from being worked, starved, or gassed to death like those they kept in line. Prisoners knew this, and most hated kapos for their cowardice and complicity. But that was by design.

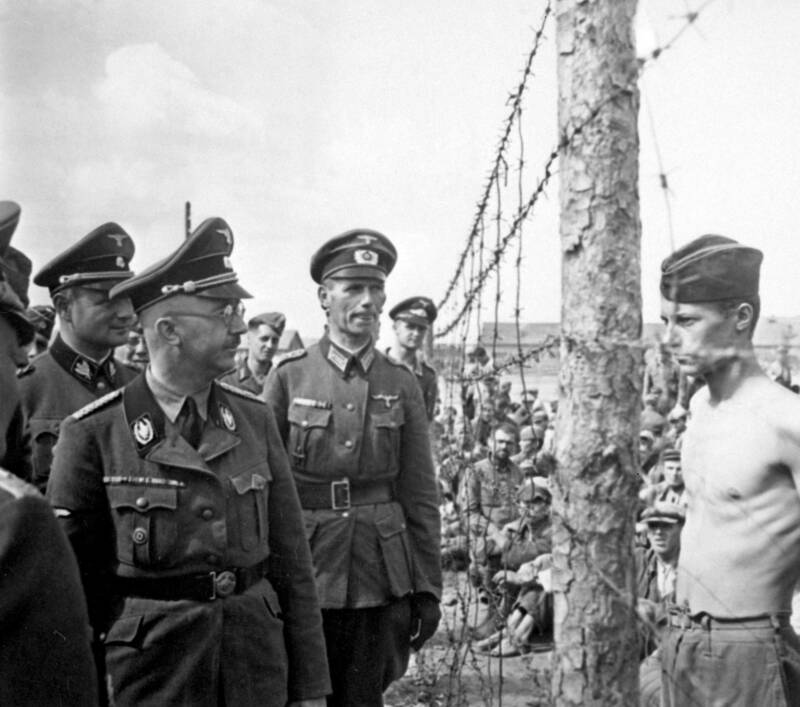

“The moment he becomes a kapo he no longer sleeps with [the other prisoners],” said Heinrich Himmler, head of the Nazi paramilitary organization called the Schutzstaffel.

Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group/Getty ImagesSS Chief Heinrich Himmler walks through a camp for Russian prisoners of war.

“He is responsible for meeting work targets, for preventing any sabotage, for seeing they are all clean and that the beds are set up… He has to get his men to work and the minute we are not satisfied with him he stops being a kapo and goes back to sleeping with the others. He knows only too well that they will kill him on the first night.”

He went on, “Since we don’t have enough Germans here, we use others — of course, a French kapo for the Poles, a Polish kapo for the Russians; we pit one nation against another.”

Holocaust survivor Primo Levi was more holistic than Himmler in his assessment. In his book, The Drowned and the Saved, Levi argued that there was an emotional element of the kapo‘s transformation, which helps explain their actions against fellow inmates:

“The best way to bind them is to burden them with guilt, cover them with blood, compromise them as much as possible. They will thus have established with their instigators the bond of complicity and will no longer be able to turn back.”

Wikimedia CommonsA Jewish kapo at the Salasplis concentration camp in Latvia.

After the Holocaust ended in 1945, some kapos defended their actions, saying their positions of power in concentration camps let them protect their fellow prisoners and soften their punishments; they beat them, they argued, in order to save them from the gas chambers.

But according to some survivors, kapos were “worse than the Germans.” Their beatings were even more vicious, with the added sting of betrayal.

But were kapos uniquely cruel, or did their apparent obedience to the Nazis make them merely seem more vicious in the eyes of the millions of Holocaust prisoners? Is it ever justified to betray your own people, even if there’s no other way you or your family can survive?

“Worse Than The Germans”

There were three main types of kapos: work supervisors, who went with prisoners to their fields, factories, and quarries; block supervisors, who watched over the prisoners’ barracks at night; and camp supervisors, who oversaw things like camp kitchens.

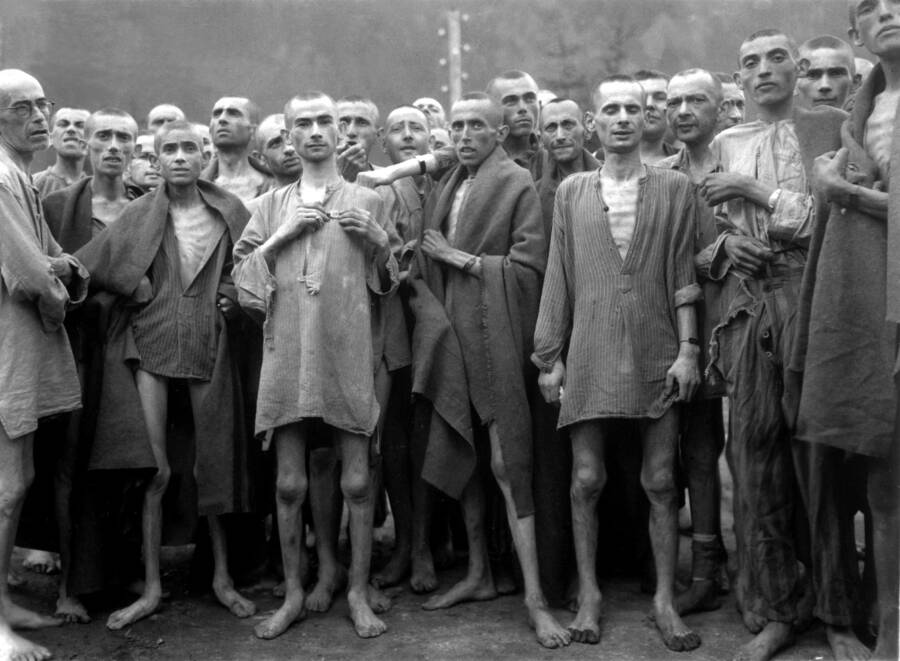

Wikimedia CommonsStarved prisoners, nearly dead from hunger, pose in concentration camp in Ebensee, Austria. The camp was reputedly used for “scientific” experiments. May 1945.

At the death camps, there were also sonderkommandos who dealt with the dead, removing corpses from gas chambers, harvesting metal teeth, and moving them to crematoriums.

Cruelty was rampant. At meals, prisoners who pushed in line or tried to get more servings would be beaten by the kapos who served them. Throughout the day, kapos were tasked with keeping order, and some them would sadistically exploit their authority.

In the 1952 trial of Yehezkel Enigster, witnesses testified that he’d walk “with a wire-club covered with rubber, which he used to hit whoever happens to cross his path, whenever he pleased.”

“I spent three years in the camps and never encountered a kapo who behaved as badly… toward Jews,” said one witness.

Some kapos took things even further. In 1965, at the culmination of the first Frankfurt Auschwitz Trial, Emil Bednarek was given life imprisonment for 14 counts of murder. As one prisoner described:

“From time to time they’d check to see if someone had lice, and the prisoner with lice was hit by clubs. A comrade of mine named Chaim Birnfeld slept next to me on the third floor of the bunk. He probably had a lot of lice, because Bednarek hit him terribly, and he may have injured his spine. Birnfeld wept and wailed through the night. In the morning he lay dead on the bunk.”

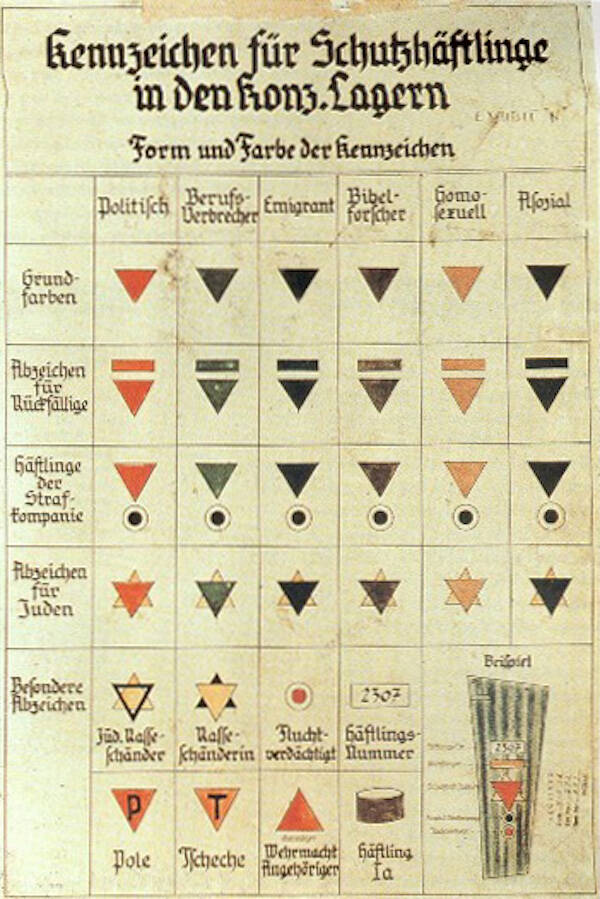

Wikimedia CommonsDifferent ethnic and political groups were forced to wear different kinds of armbands in the Nazis’ concentration camps.

In his defense, Bednarek argued that his actions were justified by the ruthlessness of the Nazis above him: “If I had not handed out the few blows,” he said in an interview from prison in 1974, “the prisoners would have been much worse punished.”

Kapos And Sexual Abuse In The Concentration Camps

Kapos played an integral role in the Nazis’ scheme to not only beat, kill, and psychologically abuse prisoners — but to sexually abuse them as well.

Yad Vashem/Wikimedia CommonsFemale prisoners during “roll call” at Auschwitz.

The Nazis set up brothels in several concentration camps and filled them with non-Jewish female prisoners. The hope was that a visit to the brothel would boost prisoners’ productivity (and “cure” homosexual men), but the only prisoners with enough strength to have sex were the kapos.

Kapos’ actions were strictly policed even inside the brothels. German men could only go to German women; Slavic men could only go to Slavic women.

It was state-sanctioned, systemized rape.

But the sexual abuse didn’t end there. Many kapos had piepels, pre-adolescent or young adolescent boys who were forced into sexual relationships with kapos in order to survive. In most cases, the boys served as sexual substitutes for women, and in return they’d receive food or protection.

According to the Times of Israel, one former piepel recalled “how, as a boy in Auschwitz, he was raped by an especially cruel kapo who forced bread into his mouth to shut him up during the rape… He isn’t completely comfortable calling what happened to him rape because he willingly ate the bread.”

Wikimedia Commons.Children liberated from Auschwitz in 1945.

There are also, of course, other reasons that people might have pursued the kapo position. Some of the sonderkommando are thought to have only taken their gruesome jobs — cleaning, stripping, burning and burying the dead — because it allowed them to check on or ask about female relatives kept segregated in the women’s camp.

The Case Of The Kapo Eliezer Gruenbaum

The case of Eliezer Gruenbaum — a kapo for about a year and a half in the Auschwitz II-Birkenau concentration camp in southern Poland — may not necessarily be representative of all kapos’ experiences. But among the numerous firsthand accounts by Holocaust survivors, Gruenbaum’s memoirs are the only ones written by a former kapo.

His writings — as well as his and other witnesses’ testimonies given during post-war inquiries in France and Poland — provide a special, crucial glimpse into the psyche of a man who was charged with punishing his fellow prisoners.

Gruenbaum did not volunteer to be a kapo; his friends volunteered for him while he was asleep. The head of his living quarters in Birkenau’s Block 9 asked his newly arrived group to nominate a representative to join the block officers, and they picked Gruenbaum.

Wikimedia CommonsArmband of a Jewish oberkapo from the concentration camps.

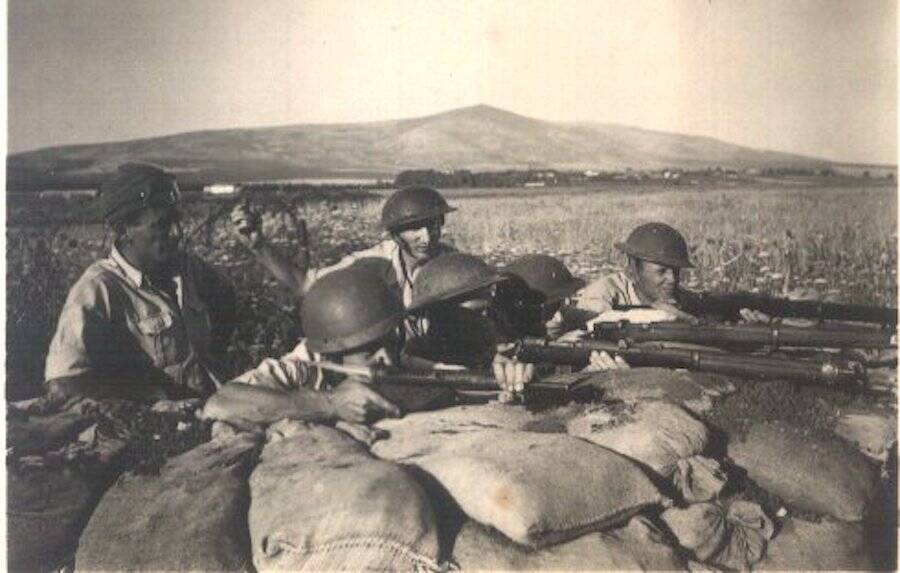

They felt they could trust him to withstand the pressures of a kapo, as he’d proved himself in the Spanish Civil War. He spoke Polish and German, making him a good go-between for the prisoners and guards, and his father was a prominent Polish-Jewish leader, which they thought would give him good standing among the prisoners.

In the summer of 1942, Gruenbaum was appointed “chief of prisoners” of his block, a position he would more or less maintain until January 1944, when he was demoted to laborer status and assigned to dig a broader and deeper channel for Poland’s Vistula River.

After a few months of digging, he was sent to the Monowitz concentration camp and then to the mining camp at Jawischowitz. In January 1945 he was sent to Buchenwald in what would be his final transfer of the Holocaust; World War II ended the following May.

Liberation Day

After American troops liberated Buchenwald, the first thing Eliezer Gruenbaum wanted to do was go home to Poland.

Wikimedia CommonsU.K. Prime Minister Winston Churchill, U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and USSR Premier Josef Stalin at the Yalta Conference. February 1945.

Under the conditions of the 1945 Yalta Conference, Poland was given over to a provisional communist party run from Moscow.

Though many Polish nationalists felt betrayed by the allies’ decision to ignore Poland’s non-communist government-in-exile, Gruenbaum was glad. He was a devoted communist, and he had always wanted a communist Poland.

Upon arrival, he attempted to join the Polish Communist Party, but party officials were suspicious of his time as a kapo and opened an official inquiry.

If he had willfully hurt or tortured prisoners — or, according to some rumors, had stolen their food to trade for alcohol — then that would have been an absolute violation of the party’s laws. It didn’t matter whether he did those things only because he thought he had to.

While the committee delayed and debated their decision on whether to bar him from their ranks, Gruenbaum decided to go to Paris. The city boasted a large number of communist Poles and Jews before the war, and he was certain he could find comrades there.

Having long ago rejected his father’s Zionism, he passed out fliers urging Polish Jews “to return to a homeland wiped clean of antisemitism and desperately in need of people prepared to build a new life, a life of socialism and social justice.”

Wikimedia CommonsSurvivors of the Ohrdruf concentration camp in Germany demonstrate Nazi torture methods for Gen. Dwight Eisenhower and others after being liberated. April 12, 1945.

But his former fellow inmates spotted him. “Arrest him! Arrest him! Here’s the murderer from Auschwitz!” shouted one man. “It’s him — the monster from Block 9 at Auschwitz!” said another.

The next day, the police issued a warrant for Gruenbaum’s arrest; one witness told police that Gruenbaum had been “the head of the Birkenau death camp.”

And so Gruenbaum’s kapo activities underwent two official investigations. The Communist Party of Poland expelled him, while after a grueling eight months of questioning the French court ultimately ruled that his case fell beyond its jurisdiction.

Gruenbaum, realizing he had a target on his back in Europe, finally agreed to follow his family to Palestine.

What Did Eliezer Gruenbaum Do?

The accusations against Gruenbaum presented in Paris were explicit and grotesque. By these accounts, Gruenbaum was not a good communist biding his time in a bad situation. He was a monster.

Gruenbaum was said to have kicked an old man to death for asking for more soup. Another accuser said the former kapo had beaten his son to death with a stick.

Wikimedia CommonsEliezer Gruenbaum was one of thousands of Poles who fought in the Spanish Civil War in the 1930s.

Some witnesses claimed Gruenbaum told them “no one has ever come out of here,” and that he had taken part in selecting people to die in the gas chambers.

Eliezer denied all of the accusations, pointing out how the prisoners in his care had maintained better health, and he’d hidden the sick so they wouldn’t be killed. His block’s mortality rate was only half the mortality rate of others. Yes, he did some bad things, he argued, but by and large he did what he thought would ultimately minimize harm.

He did, however, cryptically state that the period from which many of the accusations stemmed — 1942-1943 — had been “personally, a very difficult time.”

“What then, is the source of these persistent accusations against you, from people in responsible positions?” asked his French inquisitors.

“I have a hard time answering that,” he replied. “People were hurt more by my actions than they would have been if they had been performed by a person with an unfamiliar name,” he suggested. Or perhaps he had “gone too far.”

But according to his accusers, he acted so savagely because he thought no one who witnessed his actions would ever make it out of Birkenau alive.

Hope Is Like Opium

One observation Gruenbaum made while a kapo wouldn’t stop bothering him.

The inmates outnumbered SS officers and other authorities at Auschwitz by a considerable margin. Especially early on, before there were as many sick and starving in the population, if the prisoners had risen up, they could have changed their situation for the better. So why didn’t they?

FlickrOne of Auschwitz’s gas chambers as it appears today.

In his surviving writings from after the war, Gruenbaum described watching starved men crawl like worms to eat crumbs of bread thrown to them for the kapos’ amusement, prisoners pushing and shoving to lick spilled soup off of another prisoner’s body, pulling stained and disgusting clothing off of people killed by dysentery to give a living prisoner just one more thin shield against the cold.

“Can hope kill?” he wrote. “Can hope be considered a basic cause, a fundamental element of criminal calculation in the processing of plans for mass murder?”

The kapos who distributed prisoner mail would routinely hold back letters until morale was at its lowest. These, Gruenbaum thought, were not just a source of emotional support, they were part of the comforting “lie” that kept them in place: that there was a world to go back to and that one day outside forces would close the camp to free them.

It kept prisoners alive and waiting, but for many of them, death would be their only liberation.

In January 1944, Gruenbaum visited a block of 800 people who had been sentenced to die in the gas chambers. They spent two days quietly waiting for death, and some asked him to notify their friends, “delud[ing] themselves into thinking that some sort of intervention could still save them.”

When he arrived at a sobbing group of teenagers, another prisoner asked if he could say anything to comfort them. Gruenbaum snapped. Tapping into an “unconscious” anger, he began shouting:

“You want to delude yourselves up to the last minute! You don’t want to look your bitter fate directly in the eye! Who is guarding you here? Why are you sitting quietly? Am I or that kid [one of the four prisoners who were guarding the two blocks] stopping you? Don’t you know what you should be doing?”

But just as ordinary prisoners could have revolted, the kapos could have stopped doing their jobs. They probably would have been killed, but they could have made a real impact; the camps could not have run without kapos.

Wikimedia Commons.Sonderkommandos disposing of bodies at Auschwitz in August 1944.

When Gruenbaum wrote that “hope functioned as a soporific drug, like opium” to explain why prisoners continued to follow the camp’s routine, it not only mirrored Marx’s writings on religion, it explained why he continued as a kapo.

With the hope of planning an escape, of being useful to other political prisoners, of eventually returning to a free and communist Poland, Gruenbaum could convince himself that what he was doing made sense. Without that hope, there would only have been the horror.

After the war, however, it seems Gruenbaum’s earlier hopes were replaced with a new one: making people understand why he did what he did.

Finding A New And Final Homeland

After eight months, the French court ruled that Gruenbaum’s case was beyond its jurisdiction. Similarly, the Polish Communist Party was unable to confirm the accounts of misbehavior on Gruenbaum’s part but refused to offer him membership.

Realizing that he had no more connection to the radical communities to which he’d devoted himself and that life in Soviet Poland without a political party to depend on might be dangerous, he finally agreed to join his family in Palestine.

His father, Yitzhak, had joined him in Paris in 1945 after a years-long search for his estranged son, and he brought him to their new home.

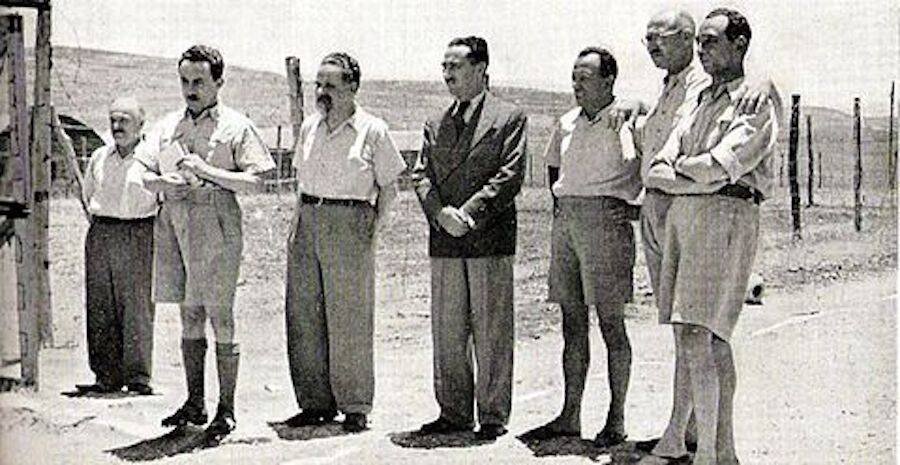

Wikimedia CommonsYitzhak Gruenbaum (third from left) with other officials at a detention camp in Palestine. 1946.

In Palestine, Gruenbaum wrote extensively in his journal about his brutal and confusing memories of his kapo days.

His father, Yitzhak, was a prominent Zionist and had been a parliamentarian back in Poland; he had been called “the king of the Jews” on more than one occasion. When his rivals heard about Eliezer’s return and what he had been accused of doing, they seized on it as a political weapon.

Letters and new accusations against Eliezer were published in Jewish newspapers. There was also discussion of opening a new case against Eliezer in Palestine, citing the existence of “additional witnesses who were not interrogated in Paris.”

Within a few years, this almost certainly would have been what happened. Following the passage of the Nazi and Nazi Collaborators (Punishment) Law in 1950, a series of kapo trials took place.

The harshest sentence given to a Jewish kapo was only 18 months, and many were sentenced to time served and released. But with the wounds of the Holocaust still fresh, no system in place, and Yitzhak Gruenbaum’s controversial popularity, there’s no reason to assume Eliezer’s fate would have been the same.

But he would never face an Israeli court.

In 1948, the Arab-Israeli War erupted after Israel declared independence, spurring military incursions from Egypt, Transjordan, Syria, and Iraq.

Eliezer went to enlist but was denied because of his kapo past. His father successfully petitioned David Ben-Gurion, another Pole and the future first prime minister of Israel, to admit him.

Wikimedia CommonsIsraeli soldiers in shooting positions during the Arab-Israeli War. Afula, Israel, 1945.

On May 22, 1948, just a week after the start of the war, according to the official version of events, Eliezer Gruenbaum was with his battalion on the way to engage the enemy when their vehicle was hit by a shell. Their commander killed, Gruenbaum was struck by shrapnel in the face, losing consciousness from blood loss before recovering.

Emerging from the convoy, he adopted a machine gunner’s pose, maintaining fire on the opposing forces while his men regrouped. Amid the fighting, Gruenbaum was shot in the head and died.

There are other theories as to how Eliezer Gruenbaum died. One, disproven but popular for many years due to its support from Yitzhak Gruenbaum’s enemies, is that Eliezer was shot in the back by his own forces for the crimes he committed in Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Another popular, and still possible, theory is that he killed himself. And when you think about it, even the official story of “a wounded man’s desperate, futile last stand against an enemy army” can be interpreted as a kind of suicide.

By surviving past the end of World War II and dying in battle, Gruenbaum may have escaped an even uglier fate.

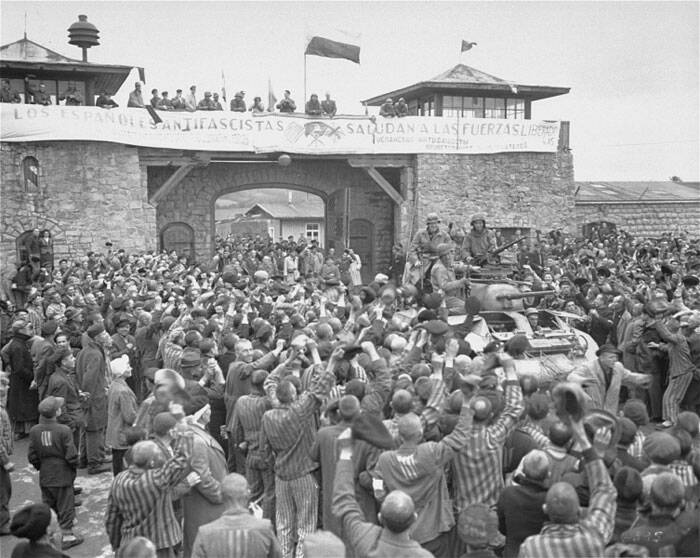

Many kapos who faced their former subordinates after the war met grisly ends. After the Mauthausen concentration camp was liberated, for instance, most of the kapos were lynched by an angry mob of prisoners.

U.S. Holocaust Memorial MuseumThe U.S. Army liberated the Mauthausen concentration camp in May 1945, whereafter the prisoners proceeded to lynch their former kapos.

One Mauthausen survivor described the events in gruesome detail:

“From one o’clock in the afternoon on, we knew that the Americans were at the gates of the camp, and we had begun our purging process. It was relatively simple. Ten, 15, or sometimes 20 of us went to blocks… where all of the German scum had taken refuge, those who were kapos just yesterday, block bosses, room chiefs, etc., who had, over the years been responsible for 150,000 deaths of men of all nationalities… Every German brute discovered in one of these blocks was hauled into the roll call yard. They were going to suffer when they died, in the way they had made our comrades suffer and die. Our only weapons were our wooden-soled shoes, but we more than made up in numbers and rage for this rudimentary equipment. Every minute a new group of deportees arrived in the roll call yard, dragging a former torturer. He was stunned and knocked down. Everyone who had a sabot on his foot, or in his hand, leaped on the body and face and stamped and struck until the guts came spilling out, and the head was a flattened shapeless mass of flesh.”

Contemplating Kapos’ Complicated Legacy

We may never know the truth of all the accusations against Eliezer Gruenbaum, or why, as he and his father claimed, camp survivors who knew him would make up such terrible stories if he were indeed innocent. But when it comes to the Second World War, and the Holocaust in general, there are far more uncomfortable questions than satisfying answers.

Gruenbaum’s memoir begins with this allegorical passage:

“We have all undoubtedly seen images at the cinema of a passenger ship sinking on the high seas; panic on deck; women and children first; a throng of people crazed with fear rushing the lifeboats; the ability to think vanishes. All that remains is a single ambition — to live! And at the boats stand the officers, guns drawn, stopping the crowd as shots ring out. We lived for days, weeks and years on the deck of a sinking ship.”

Unless we ourselves have been on that sinking ship and felt its terror, Gruenbaum implies, we cannot understand the reality of the situation. Neither can we understand the things people in it would do out of panic, fear, and misplaced anger.

Perhaps in his position, we might have made different choices. I am sure we all hope we would. But the evidence suggests that when placed into such an evil system, individuals who can come out unscathed are few and far between.

After learning about the complicated legacy of kapos, delve into the life of Simon Wiesenthal, the Holocaust survivor-turned-Nazi hunter. Then, take a look at these 44 tragic photos inside the Nazis’ Bergen-Belsen concentration camp.