The Nazis told their prisoners Arbeit macht frei, or "Work sets you free." In truth, millions of forced laborers were worked to death.

In December 2009, the infamous sign above the entrance to the Auschwitz Concentration Camp was stolen. When recovered two days later, Polish police discovered the thieves had cut the metal placard into three pieces. Each third contained a single word from the sentence every arrival at the Nazi death camp and every enslaved prisoner trapped within its walls had been forced to read day in and day out: Arbeit Macht Frei or “Work sets you free.”

The same message could be found at other camps like Dachau, Sachsenhausen, and Buchenwald. In every case, their implied “promise” was a lie meant to pacify massive imprisoned populations — that there was, somehow, a way out.

Wikimedia CommonsPhotograph of Auschwitz’s gate with the Arbeit Macht Frei sign. Present day.

Although best remembered 75 years later as the sites of mass murder, the concentration camps built by the Nazi regime and its supporters were more than death camps and, in most cases, did not start as such. In fact, many of them started as slave labor camps — driven by business interests, cultural values, and a cold, cruel rationale.

The Mechanics Of Nazi Nationalism

In most discussions of the Second World War, it is often overlooked that the Nazi Party was initially, at least on paper, a labor movement. Adolf Hitler and his government rose to power in 1933 with the promise of improving the lives of the German people and the strength of the German economy — both deeply affected by a bitter defeat in the First World War and the chafing penalties imposed by the Treaty of Versailles.

In his book, Mein Kampf, or My Struggle, and in other public statements, Hitler argued for a new German self-conception. According to him, the war had not been lost on the battlefield but instead through the traitorous, back-stabbing deals cut by Marxists, Jews, and various other “bad actors” against the German people, or the volk. With these people removed and power taken from their hands, the Nazis promised, the German people would prosper.

Wikimedia CommonsNazi soldiers enforce a boycott of Jewish businesses. April 1, 1933.

To a large percentage of Germans, this message was as exciting as it was intoxicating. Appointed chancellor on Jan. 30, 1933, by April 1 Hitler announced a nationwide boycott of Jewish-owned businesses. Six days later, he further ordered the resignation of all Jews from the legal profession and civil service.

By July, naturalized German Jews were stripped of their citizenship, with new laws creating barriers isolating the Jewish population and its businesses from the rest of the market, and heavily limiting immigration into Germany.

SS “Socialism”: Profit Less Valuable Than The Volk

To go with their newfound power, the Nazis began building new networks. On paper, the paramilitary Schutzstaffel, or SS, was intended to resemble a knightly or fraternal order. In practice, it was the bureaucratic mechanism of an authoritarian police state, rounding up the racially undesirable, political opponents, the chronically unemployed, and the potentially disloyal for confinement in concentration camps.

More ethnic Germans were seeing better employment prospects and stagnant segments of the market were opening up to innovation. But it was clear that German “success” was something of an illusion — ethnic Germans’ opportunities stemmed from the removal of large parts of the “old” population.

Germany’s official labor ideology was reflected in the “Strength Through Joy” and “Beauty of Work” labor initiatives, which lead to events like the Berlin Olympics and the creation of “the people’s car,” or the Volkswagen. Profit was seen as less important than the health of the volk, an idea that carried over to the structure of Nazi institutions.

The SS would take over businesses and run them themselves. But no single faction, division, or company was allowed to prosper alone: If one of them failed, they’d use profits from a successful one to help bolster it.

Wikimedia CommonsReich Labor Service Squad Drilling, 1940.

This communal vision carried over into the regime’s massive building programs. In 1935, the same year the Nuremberg Race Laws were passed, further isolating the Jewish population, the Reichsarbeitsdienst, or “Reich Labor Service,” created a system within which young German men and women could be conscripted for up to six months laboring on behalf of the fatherland.

In as attempt to actualize the Nazi conception of Germany not just as a nation but as an empire on par with Rome, large-scale construction projects such as the autobahn highway network were started. Others included new government offices in Berlin, and a parade ground and national stadium to be built in Nuremberg by Hitler’s favorite architect, Albert Speer.

Colossal Construction And Imperial Ambitions

Speer’s preferred construction material was stone. He insisted that the choice of stone was purely aesthetic, another means of embodying the Nazis’ neoclassical ambitions.

But the decision served other purposes. Much like the Westwall or Seigfried Line – a massive concrete barrier built along the border with France — these considerations had a second purpose: conserving metal and steel for the munitions, airplanes, and tanks which would be necessary for the fighting to come.

Among the guiding tenets of Germany’s self-conception was that all great nations needed territory in order to grow, something it had been denied by international powers following WWI. For the Nazis, the need for living space, or lebensraum, outweighed the need for peace in Europe or the autonomy of nations like Austria, Czechoslovakia, Poland, and Ukraine. War, like mass genocide, was often seen as a means to an end, a way to reshape the world in accordance with Aryan ideals.

As Heinrich Himmler stated shortly after the war’s start in 1939, “The war will have no meaning if, 20 years hence, we have not undertaken a totally German settlement of the occupied territories.” The Nazis’ dream was to occupy most of Eastern Europe, with the German elite ruling over their new lands from sheltered enclaves constructed and supported by the subjugated population.

With such a grand goal in mind, Himmler believed, socioeconomic preparation would be required to have the manpower and materials to build the empire of their imaginations. “If we do not provide the bricks here, if we do not fill our camps full with slaves [to] build our cities, our towns, our farmsteads, we will not have the money after the long years of war.”

Wikimedia CommonsHeinrich Himmler inspects the Dachau concentration camp. May 8, 1936.

Although Himmler himself would never lose sight of this goal – devoting more than 50 percent of the nation’s GDP toward expansionist construction as late as 1942 – his utopian ideal ran into trouble as soon as the real fighting began.

Following the 1938 annexation of Austria by Nazi Germany, the Nazis came into possession of all of Austria’s territory — and its 200,000 Jews. While Germany was already well underway in its efforts to isolate and steal from its own Jewish population of 600,000, this new group was a new problem, mostly made up of poor rural families who couldn’t afford to flee.

On December 20, 1938, the Reich Institute for Labor Placement and Unemployment Insurance introduced segregated and compulsory labor (Geschlossener Arbeitseinsatz) for unemployed German and Austrian Jews registered with the labor offices (Arbeitsämter). For their official explanation, the Nazis said their government had “no interest” in supporting Jews fit for work “from public funds without receiving anything in return.”

In other words, if you were Jewish and you were poor, the government could force you to do just about anything.

“Slaves To Build Our Cities, Our Towns, Our Farmsteads”

Although today, the term “concentration camp” is most often thought of in terms of death camps and gas chambers, the image does not really capture their full capacity and purpose for most of the war.

While the mass murder of “undesirables” — Jews, Slavs, Roma, homosexuals, Freemasons, and the “incurably sick” — was in full gear from 1941 to 1945, the coordinated plan for the extermination of Europe’s Jewish population was not publicly known until the spring of 1942, when news broke in the United States and the rest of the West of hundreds of thousands of Jews in Latvia, Estonia, Lithuania, Poland, and elsewhere being rounded up and murdered.

For the most part, the concentration camps were originally intended to serve as slave-run factories for goods and arms. The size of small cities, millions of people were either killed or forced into slave labor at the Nazis’ concentration camps, with a focus on the absolute quantity over the “qualities” of workers.

Natzweiler-Struthof, the first concentration camp built in France following Germany’s invasion in 1940, was, like many of the early camps, primarily a quarry. Its location was selected specifically for its stores of granite, with which Albert Speer intended to construct his grand Deutsches Stadion in Nuremberg.

Although not designed as death camps (Natzweiler-Struthof wouldn’t get a gas chamber until August 1943), quarry camps could be just as cruel. There is perhaps no better way to prove this than to look at the Mauthausen-Gusen concentration camp, which was practically the poster child for the policy of “annihilation through work.”

Annihilation Through Work And Kapo Conscription

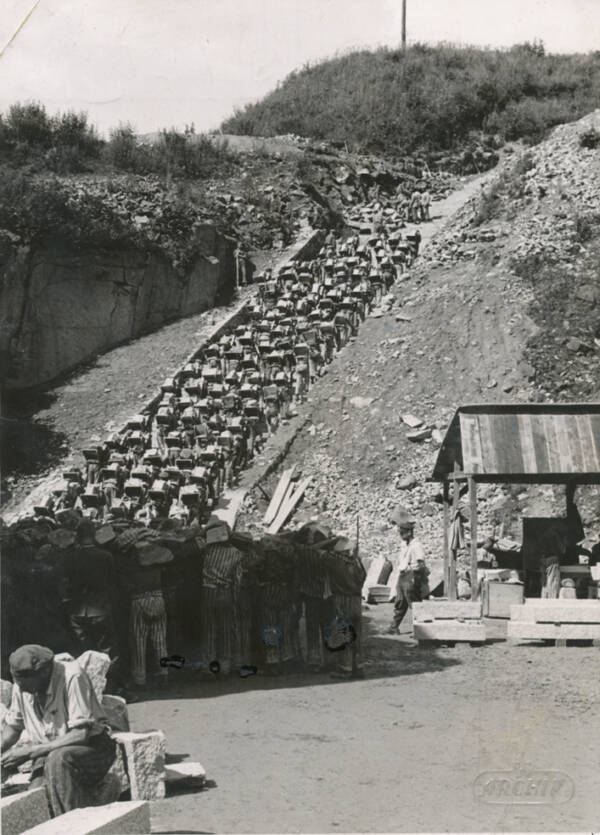

Wikimedia CommonsThe “Stairs of Death,” full of prisoners at the Mauthausen concentration camp.

At Mauthausen, prisoners worked around the clock without food or rest, carrying enormous boulders up a 186-step staircase nicknamed “The Stairs of Death.”

If a prisoner successfully brought his load to the top, they would be sent back down for another boulder. If a prisoner’s strength gave out during the climb, they would fall back onto the line of prisoners behind them, resulting in a deadly domino reaction and crushing those at the base. Sometimes a prisoner might reach the top only to be pushed anyway out of spite.

Another deeply disturbing fact to consider: If and when a prisoner was kicked from the stairs at Mauthausen, it was not always an SS officer doing the dirty work at the top.

At many camps, some prisoners were designated Kapos. Coming from the Italian for “head,” Kapos did double duty as both prisoners and the lowest rung of concentration camp bureaucracy. Often chosen from the ranks of career criminals, Kapos were selected in the hopes their self-interest and lack of scruples would allow SS officers to outsource the ugliest aspects of their jobs.

In exchange for better food, freedom from hard labor, and the right to one’s own room and civilian clothes, as many as 10 percent of all concentration camp prisoners became complicit in the suffering of the remainder. Though for many Kapos, it was an impossible choice: Their chances of survival were 10 times greater than the average prisoner’s.

Wikimedia CommonsAt Auschwitz, Nazi officials choose which newly arrived Hungarian Jews will work and which will be sent to the gas chamber to die. 1944.

Selection Of Terrible Choices

By the mid-1940s, processing new arrivals at a concentration camp had coalesced into a routine. Those fit enough to work would be taken one way. The sick, old, pregnant, deformed, and under-12 would be taken to a “sick barrack” or “infirmary.” They would never be seen again.

The unfit to work would arrive in a tiled room, greeted by instruction signs to neatly take off their clothes and prepare for a group shower. When all their clothes were hung on provided pegs and every person had been locked inside the airtight room, the poisonous gas Zyklon B would be pumped in through “shower heads” in the ceiling.

When all the prisoners were dead, the door would be reopened and a crew of sonderkommandos would be tasked with searching for valuables, collecting the clothes, checking the teeth of corpses for gold fillings, and then either burning the bodies or dumping them in a mass grave.

In nearly every case, the sonderkommandos were prisoners, just like the people they disposed of. Most often young, healthy, strong Jewish men, these “special unit” members carried out their duties in exchange for the promise that they and their immediate families would be spared from death.

Like the myth of Arbeit Macht Frei, this was usually a lie. As slaves, the sonderkommandos were considered disposable. Complicit in atrocious crimes, quarantined from the outside world, and without anything close to human rights, most sonderkommandos would be gassed themselves to ensure their silence about what they knew.

Wikimedia CommonsSonderkommandos burning corpses at Auschwitz. 1944.

Forced Prostitution And Sexual Slavery

Only infrequently mentioned until the 1990s, Nazi war crimes involved another form of forced labor as well: sexual slavery. Brothels were installed at many camps to improve morale among SS officers and as a “reward” for well-behaved Kapos.

Sometimes normal prisoners would be “gifted” visits to the brothels, though in these cases SS officers were always present to ensure nothing resembling plotting took place behind closed doors. Among a particular class of prisoners — the homosexual population — such visits were termed “therapy,” a means of curing them by introducing them to the “fairer sex.”

At first, the brothels were staffed by non-Jewish prisoners from Ravensbrück, an all-female concentration camp originally designated for political dissidents, though others, like Auschwitz, would eventually recruit from their own populations with false promises of better treatment and protection from harm.

Auschwitz’s brothel, “The Puff,” was located right by the main entrance, the Arbeit Macht Frei sign in full view. On average, the women had to have sex with six to eight men per night — in a two-hour time span.

The Mask Of Civilization

Some forms of forced labor were more “civilized.” At Auschwitz, for instance, one group of female prisoners served as the staff of the “Upper Tailoring Studio,” a private dressmaking shop for the wives of SS officers stationed at the facility.

As strange as it sounds, entire German families lived in and around the concentration camps. They were like factory towns complete with supermarkets, highways and traffic courts. In some ways, the camps presented a chance to see Himmler’s dream in action: elite Germans being waited on by a subservient slave class.

For instance, Rudolf Höss, the Kommandant of Auschwitz from 1940 to 1945, maintained a full wait staff at his villa, complete with nannies, gardeners, and other servants pulled from the prisoner population.

Wikimedia CommonsPrisoners sorting through confiscated property. 1944.

If we can learn anything about a person’s character by how they treat defenseless people at their mercy, there are few worse individuals than a well-dressed doctor and SS officer who was known to whistle Wagner and give out candy to children.

Josef Mengele, “the Angel of Death of Auschwitz,” had originally wanted to be a dentist before his industrialist father had noted the opportunities offered by the rise of the Third Reich.

Guided by politics, Mengele went on to study genetics and heredity — popular disciplines among Nazis — and the Mengele and Sons company became the primary farm equipment supplier for the regime.

Upon his 1943 arrival at Auschwitz while in his early 30s, Mengele took to his role as a camp scientist and experimental surgeon with terrifying speed. Given his first assignment to rid the camp of a typhus outbreak, Mengele ordered the deaths of all those infected or possibly infected, murdering more than 400 people. Thousands more would be killed under his supervision.

Slave Doctors And Human Experimentation

Just as the camps’ other horrors can be tied to Himmler’s “Peace Plan” vision for colonies yet to come, Mengele’s worst crimes were committed to help create the Nazis’ ideal future — at least on paper. The government backed the study of twins because it hoped scientists like Mengele could ensure a larger, purer Aryan generation by boosting birthrates. Also, identical twins come with a natural control group for any and all experimentation.

Wikimedia CommonsChildren liberated from Auschwitz, including several groups of twins for Josef Mengele’s experiments. 1945.

Even the Jewish prisoner Miklós Nyiszli, a doctor, could understand the possibilities a death camp provided for researchers.

At Auschwitz, he said, it was possible to collect otherwise impossible information — such as what might be learned from studying the corpses of two identical twins, one serving as the experiment and the other as the control. “Where in normal life is there the case, bordering on a miracle, that twins die at the same place at the same time?…In Auschwitz camp, there are several hundred pairs of twins, and their deaths, in turn, present several hundred opportunities!”

Although Nyiszli understood what the Nazi scientists were doing, he had no desire to participate in it. However, he did not have a choice. Separated from the other prisoners upon his arrival at Auschwitz because of his background in surgery, he was one of several slave doctors forced to serve as Mengele’s assistants to ensure the safety of their families.

In addition to the twin experiments — some of which involved injecting dye directly into a child’s eyeball — he was tasked with performing autopsies on newly murdered corpses and collecting specimens, in one case overseeing the death and cremation of a father and son in order to secure their skeletons.

After the war’s end and Nyiszli’s liberation, he said he could never hold a scalpel again. It brought back too many terrible memories.

In the words of another of Mengele’s unwilling assistants, he could never stop wondering why Mengele had done and made him do so many terrible things. “We ourselves who were there, and who have always asked ourselves the question and will ask it until the end of our lives, we will never understand it, because it cannot be understood.”

Finding Opportunities And Recognizing Potential

Consistently, across different countries and industries, there were always doctors, scientists, and businessmen who saw the potential “opportunities” concentration camps provided.

In a sense, that was even the reaction of the United States upon the discovery of the secret facility located beneath the Dora-Mittelbau camp in central Germany.

Wikimedia CommonsA rusty V-2 engine found at the Dora-Mittelbau camp. 2012.

Starting in September of 1944, it seemed like Germany’s sole chance of salvation was its new “wonder weapon,” the vergeltungswaffe-2 (“retribution weapon 2”), also known as the V-2 rocket, the world’s first long-range, guided ballistic missile.

A technological marvel for its time, the V-2 bombardments on London, Antwerp, and Liege were too little too late for Germany’s war effort. Despite its fame, the V-2 might be the weapon with the greatest “inverse” effect in history. It killed far more people in its production than it ever did in use. Each and every one was built by prisoners working in a cramped, dark, subterranean tunnel dug by slaves.

Placing the technology’s potential above the cruelty that produced it, the Americans offered amnesty to the program’s top scientist: Wernher von Braun, an officer in the SS.

Unwilling Participant Or Historical White Wash?

While von Braun’s membership in the Nazi Party is undisputed, his enthusiasm is a matter of debate.

Despite his high rank as an SS officer — having been promoted three times by Himmler — von Braun claimed to have only worn his uniform once and that his promotions were perfunctory.

Some survivors swear to have seen him at the Dora camp ordering or witnessing prisoner abuses, but von Braun claimed never to have been there or seen any mistreatment firsthand. By von Braun’s account, he was more or less forced to work for the Nazis — but he also told American investigators that he joined the Nazi Party in 1939 when records show he joined in 1937.

Wikimedia CommonsWernher von Braun with Nazi generals. 1941.

No matter which version is true, von Braun spent part of 1944 in a Gestapo jail cell over a joke. Tired of making bombs, he said he wished he was working on a rocket ship. As it happens, he would go on to do just that across the Atlantic, pioneering the United States’ NASA space program and winning the National Medal of Science in 1975.

Did von Braun truly regret his complicity in the deaths of tens of thousands of people? Or did his use his scientific prowess as a get-out-of-jail-free card to avoid prison or death after the war? Either way, the U.S. was more than willing to overlook his past crimes if it gave them a leg up in the space race against the Soviets.

The Good Nazi And Effective Public Relations

Even though he was the “Minister of Armaments and War Production,” Albert Speer successfully convinced the authorities at Nuremberg that he was an artist at heart, not a Nazi ideologue.

Although he served 20 years for human rights violations, Speer always vehemently denied knowledge of the Holocaust’s planning and appeared sympathetic enough in his multiple memoirs that he was termed “The Good Nazi.”

Considering the absurdity of these lies, it is amazing it took several decades for Speer to be exposed. He died in 1981, but in 2007 researchers uncovered a letter where Speer confessed to knowing that the Nazis had planned to kill “all Jews.”

Wikimedia Commons.Hitler’s favorite architect, Albert Speer, visits a munitions factory. 1944.

Despite his lies, there is truth in Speer’s assertion that all he wanted was to be “the next Schinkel” (a famous 19th-century Prussian architect). In her 1963 book, Eichmann in Jerusalem, about the trial of escaped Nazi officer Adolf Eichmann, Hannah Arendt coined the term “banality of evil” to describe the man who had become a monster.

Personally responsible for the deportation of Hungarian Jews to the concentration camps, among other crimes, Arendt found Eichmann to be neither a Nazi fanatic nor a madman. Instead, he was a bureaucrat, calmly carrying out despicable orders.

By the same token, Speer very well may only have wanted to be a famous architect. He certainly did not care how he got there.

Widespread Corporate Collaboration

To greater and lesser extents, the same can be said of many companies and corporate interests of the period. Volkswagen and its subsidiary, Porsche, started out as Nazi government programs, producing military vehicles for the German Army using forced laborers during the war.

Siemens, the electronics and consumer goods manufacturer, ran out of normal laborers by 1940 and began utilizing slave labor to keep up with demand. By 1945, they had “used the labor of” as many as 80,000 prisoners. They had nearly all of their assets seized during the American occupation of West Germany.

The Bavarian Motor Works, BMW, and Auto Union AG, the predecessor to Audi, both spent the war years manufacturing parts for motorcycles, tanks, and airplanes utilizing slavery. Some 4,500 died at just one of Auto Union’s seven labor camps.

Daimler-Benz, of Mercedes-Benz fame, actually supported the Nazis prior to Hitler’s rise, taking out full-page advertisements in the Nazis’ newspaper, the Volkischer Beobachter, and utilizing slave labor as a parts manufacturer for the military.

When in 1945 it became clear that their involvement would be exposed by Allied intervention, Daimler-Benz attempted to have all of its workers rounded up and gassed to prevent them from talking.

Holocaust OnlineA propaganda ad by Daimler-Benz, later known as Mercedes-Benz. 1940s.

Nestlé gave money to the Swiss Nazi Party in 1939, and later signed a deal making them the official chocolate provider of the Wehrmacht. Although Nestlé claims they never knowingly used slave labor, they paid $14.5 million in reparations in the year 2000, and haven’t exactly avoided unfair labor practices since.

Kodak, an American company based in New York, continues to deny any involvement with the regime or forced labor despite evidence of 250 prisoners working at its Berlin factory during the war and a $500,000 settlement payment.

Were this simply a catalog of companies who had profited off the Nazi regime, the list would be much longer and more uncomfortable. From Chase Bank buying the depreciated Reichsmarks of fleeing Jews to IBM helping Germany create a system to identify and track undesirables, this is a story with loads of dirty hands.

That is to be expected. Often in times of crisis, fascists rise by convincing wealthy stakeholders that fascism is the safest option.

Many companies fell for the Nazi Party line, but IG Farben deserves separate and special mention.

Wikimedia Commons.Heinrich Himmler visits IG Farben facilities at Auschwitz. 1944.

IG Farben: From Dye-Making To Death-Manufacturing

Founded in the years following the First World War, Interessengemeinschaft Farbenindustrie AG was a conglomerate of Germany’s largest chemical companies — including Bayer, BASF, and Agfa — which pooled their research and resources to better survive the era’s economic turmoil.

Possessing close ties to the government, some of IG Farben’s board members built gas weapons during World War I and others attended the Versailles peace talks.

Whereas before World War II, IG Farben was an internationally respected powerhouse most famous for inventing various artificial dyes, polyurethane, and other synthetic materials, after the war they were better known for their other “accomplishments.”

IG Farben manufactured Zyklon-B, the cyanide-derived poison gas used in the Nazis’ gas chambers; at Auschwitz, IG Farben ran the world’s largest fuel and rubber factories with slave labor; and on more than one occasion, IG Farben “bought” prisoners for pharmaceutical testing, quickly returning for more after they had “run out.”

As the Soviet Army approached Auschwitz, IG Farben staff destroyed their records inside the camp and burned another 15 tons of paper before the Allies captured their Frankfurt office.

In recognition of their level of collaboration, the Allies made a special example of IG Farben with the Allied Control Council Law No. 9, “Seizure of Property owned by IG Farbeninsdutrie and the Control Thereof,” for “knowingly and prominently…building up and maintaining German war potential.”

Later, in 1947, Gen. Telford Taylor, a prosecutor at the Nuremberg Trials, reconvened in the same location to try 24 IG Farben employees and executives with war crimes and crimes against humanity.

United States Holocaust Memorial MuseumDefendants at the IG Farben trial at Nuremberg, 1947.

In his opening statement, Taylor declared, “The grave charges in this case have not been laid before the Tribunal casually or unreflectingly. The indictment accuses these men of major responsibility for visiting upon mankind the most searing and catastrophic war in modern history. It accuses them of wholesale enslavement, plunder, and murder.”

Overlooking A “Common” Crime

Still, after a trial lasting 11 months, 10 of the defendants went completely unpunished.

The harshest sentence, eight years, went to Otto Ambros, an IG Farben scientist who utilized Auschwitz prisoners in the manufacture and human testing of nerve gas weaponry, and Walter Dürrfeld, the head of construction at Auschwitz. In 1951, just three years after the sentencing, U.S. High Commissioner in Germany John McCloy granted both Ambros and Dürrfeld clemency and they were released from prison.

Ambros would go on to serve as an advisor to the U.S. Army Chemical Corps and Dow Chemical, the company behind Styrofoam and Ziploc bags.

Hermann Schmitz, IG Farben’s CEO, was released in 1950 and would go on to join the advisory board of Deutsche Bank. Fritz ter Meer, a board member who helped build an IG Farben factory at Auschwitz, was released early in 1950 for good behavior. By 1956, he was chairman of the board for the newly independent and still-extant Bayer AG, the manufacturers of aspirin and Yaz birth control pills.

IG Farben not only helped the Nazis get started, they assured the regime’s armies could keep running and developed chemical weapons for their use, all while using and abusing concentration camp prisoners for their own profit.

The absurdity, however, is found in the fact that although IG Farben’s contracts with the Nazi government were lucrative, slave labor itself was not. Building entirely new factories and continually training new workers were additional costs for IG Farben, costs that they felt were balanced out, the board felt, by the political capital gained through proving their philosophical alignment with the regime. Like those organizations run by the SS itself, for IG Farben, some losses were for the good of the volk.

As the horrors of more than a half-century ago fade into memory, buildings like those at Auschwitz carry a message with them for all of us to remember.

As Nuremberg prosecutor Gen. Telford Taylor put it in his testimony at the IG Farben trial, “[These] were not the slips or lapses of otherwise well-ordered men. One does not build a stupendous war machine in a fit of passion, nor an Auschwitz factory during a passing spasm of brutality.”

At every concentration camp, someone paid for and placed every brick in each building, every roll of barbed wire, and every tile in a gas chamber.

No one man or one party can be held solely responsible for the myriad crimes committed there. But some of the culprits not only got away with it, they died free and wealthy. Some are still out there to this day.

After learning how the Nazis’ philosophy of Arbeit macht frei played out during the Holocaust, read about fertilizer and gas weaponry inventor Fritz Haber. To learn how concentration camp prisoners got back at their guards, read about the liberation of the Dachau concentration camp.