After a failed monsoon season and brutal drought, the Madras Famine impacted millions of people in India from 1876 to 1878 — and the British colonial government made the situation even worse.

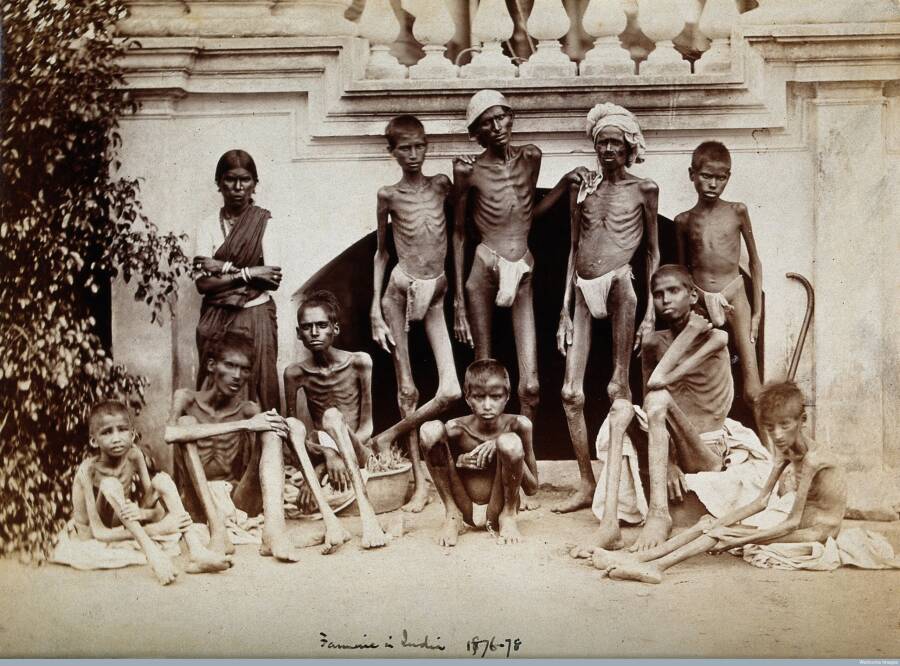

Wikimedia CommonsIt’s estimated that about 8.2 million people died during the Madras Famine of 1876-1878.

Drought struck British India after a failed monsoon season in 1876, leaving crops withering in the fields and sending food prices soaring. When the drought extended through the next summer, millions starved.

The Madras Famine, also known as the Great Famine of 1876-1878, left an estimated 8.2 million people dead across India. (Alternate estimates range anywhere from 5 million to 11 million victims.) “Whichever way the eye turned, dead bodies were to be seen,” an eyewitness reported.

From England, Florence Nightingale, the “mother of nursing,” wrote, “The more one hears about this famine, the more one feels that such a hideous record of human suffering and destruction the world has never seen before.”

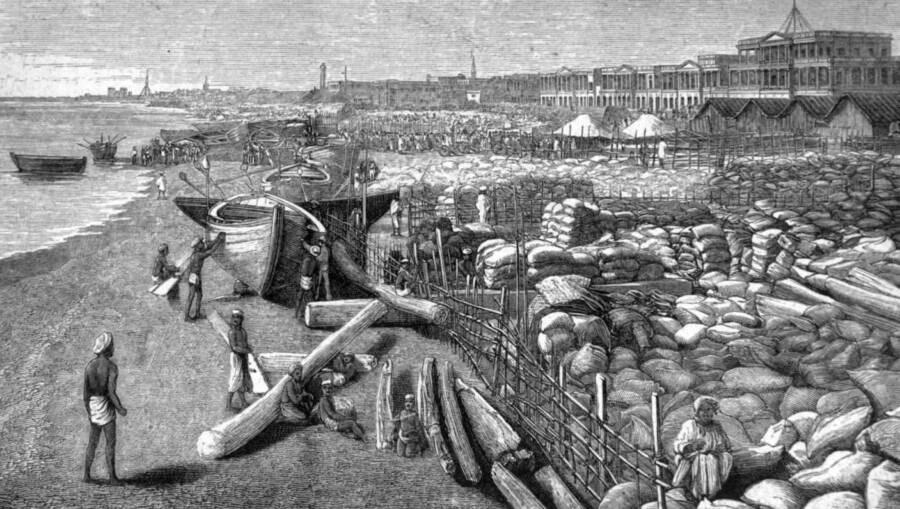

Yet as millions starved, the British exported massive amounts of grain from India to England, making colonial rulers even more wealthy.

The Beginning Of The Madras Famine

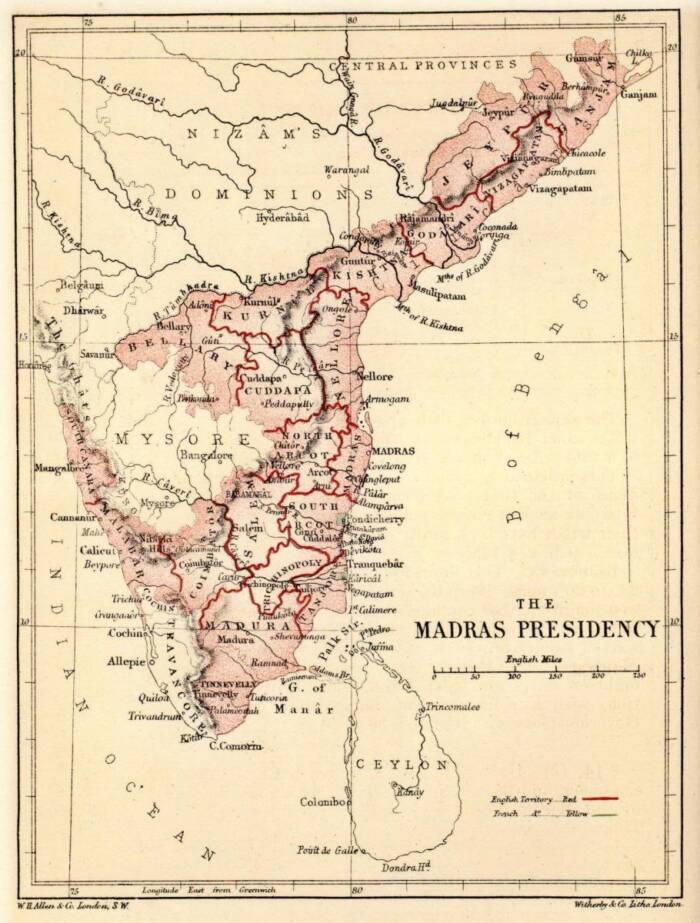

Madras, a region in British India, stretched across much of the southern portion of the country. Home to an estimated 31 million people by the 1870s, Madras grew critical grains like rice that helped feed its population. But when the monsoon season failed in 1876, the prices of grains began to climb.

Wikimedia CommonsAn 1880 map of India, showing the Madras region.

As the situation became increasingly dire, women started storming storage warehouses, determined to feed their children with stockpiled grains.

Food shortages and hunger spread beyond Madras. Before long, the nearby regions of Bombay, Mysore, and Hyderabad also faced famines. Starvation and malnutrition also paved the way for numerous diseases to sweep through the population. Cholera and malaria killed millions more.

British journalist William Digby, who was once the editor of the Madras Times, reported an average of 20 dead on the streets of Bangalore daily in August 1877. By September, that number had more than doubled.

“When troops were marched to the shooting butts for rifle practice the soldiers were horrified with the sight of bodies of men, women, and children, lying exposed and partly devoured by dogs and jackals,” Digby wrote.

How British Rule Made The Famine Worse

Why was the Madras Famine so deadly? Decades of British rule had left many of India’s peasants in debt and vulnerable to food shortages.

Fields that once grew food for local agricultural production had been converted to produce cash crops instead. British officials had also demanded indigo and cotton. During the American Civil War, the British especially pushed India to grow cotton to help fuel England’s textile industry. When the Confederacy folded and American cotton later re-entered the market, India’s farmers paid the price, especially since it was difficult for them to change existing cotton fields into ones that could grow more food.

William Digby/Wikimedia CommonsWhile millions starved during the Madras Famine, the British continued to export massive amounts of grains from India.

British land taxes also left rural farmers in debt. Peasants often turned to local moneylenders to cover their land revenue payments, leaving them in an even more precarious position if their crops failed.

Jyotirao Phule, an Indian social reformer, spoke up about this worrying situation, saying in 1883 that “our cunning government” has “established levies and taxes as they willed, and the farmer, losing his courage, has not properly tilled his lands, and therefore millions of farmers have not been able to feed themselves or cover themselves.”

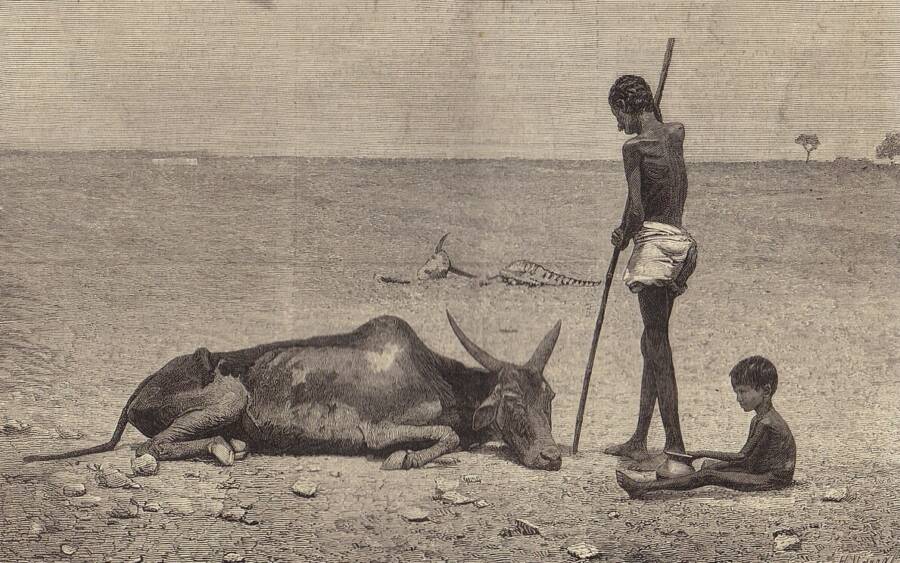

Horace Harral/Wikimedia CommonsThe Madras Famine also killed countless animals, making conditions even more dire for starving people. Ominous rumors eventually spread that some people became so desperate for food that they turned to cannibalism.

Taxes, even more so than the drought, made the famine especially deadly for the victims, Phule argued. He said, “As the farmers weakened further because of this, they started dying by the thousands in epidemics.”

Meanwhile, British administrators continued to export eye-watering amounts of grain to England. Furthermore, they also argued against government intervention in the grain markets to help the starving famine victims.

Viceroy Lord Robert Bulwer Lytton argued that it was crucial to preserve free private trade at any cost. “Free and abundant private trade cannot co-exist with Government importation. Absolute non-interference with the operations of private commercial enterprise must be the foundation of our present famine policy,” Lytton wrote in August 1877.

Lytton also declared, “I am confident that more food, whether from abroad or elsewhere, will reach Madras, if we leave private enterprise to itself, than if we paralyse it by Government competition.”

Relief Kitchens And Temple Wages

As millions continued to starve, the British colonial government eventually opened relief camps. But colonial administrators encouraged the relief kitchens to limit the food they served. According to Sir Richard Temple, appointed by the British to manage the relief programs, anything more than small amounts of food would create “dependency” among the poor.

Many famine victims were also forced to work on colonial railway projects to receive their “wage,” only about a pound of food grain, barely enough to stay alive. The stingy support became known as the “Temple wage.”

Wellcome LibraryEmaciated people were often forced to work on railways or canals to receive food from the British colonial government.

Women and children were often also told to work if they wanted food, with only the youngest children excluded from work requirements. Notably, women and children received even lower Temple wages than men.

Infamously, some British colonial photographers took pictures of these staving victims at relief camps, hoping to show the success of their relief efforts. Instead, they faced criticism for arranging photos of terribly frail people in specific poses and writing insensitive photo captions like “living skeletons” and “deserving objects of gratuitous relief.”

Inside The Dismal British Responses To Famines

The official British response to the Madras Famine mirrored the approach to other famines in India (as well as Ireland). Only about a decade before the Madras Famine, British colonial policies had also contributed to the Orissa Famine. From 1866 to 1867, an estimated one in three people in Orissa died.

Many colonial administrators framed a famine as a natural disaster that was hard to prevent and a situation that was difficult to improve. As Bengal’s colonial governor Cecil Beadon declared, “Such visitations of providence as these no government can do much either to prevent or alleviate.”

Beadon went even further, arguing that any government intervention would likely make a bad situation worse. Attempting to regulate the soaring grain prices was essentially stealing, according to Beadon.

Wikimedia CommonsAn imperial assembly held in Delhi, India in 1877 — amidst the Madras Famine.

Dadabhai Naoroji, an Indian nationalist, argued that the colonial power was draining India for its own gain. As people starved in Orissa, colonial officials in India exported more than 200 million pounds of rice to Britain.

“The destruction of a million and a half lives in one famine is a strange illustration of the worth of the life and property thus secured,” Naoroji said.

The Impact Of The Madras Famine

The Madras Famine left millions of victims dead and outraged countless people around the world. But it ultimately had little impact on the British rule of India, which would endure for many more decades.

Still, British journalist William Digby felt compelled to publish a disturbing, detailed account on the famine in 1878. He hoped that writing about the devastation might prevent future humanitarian crises.

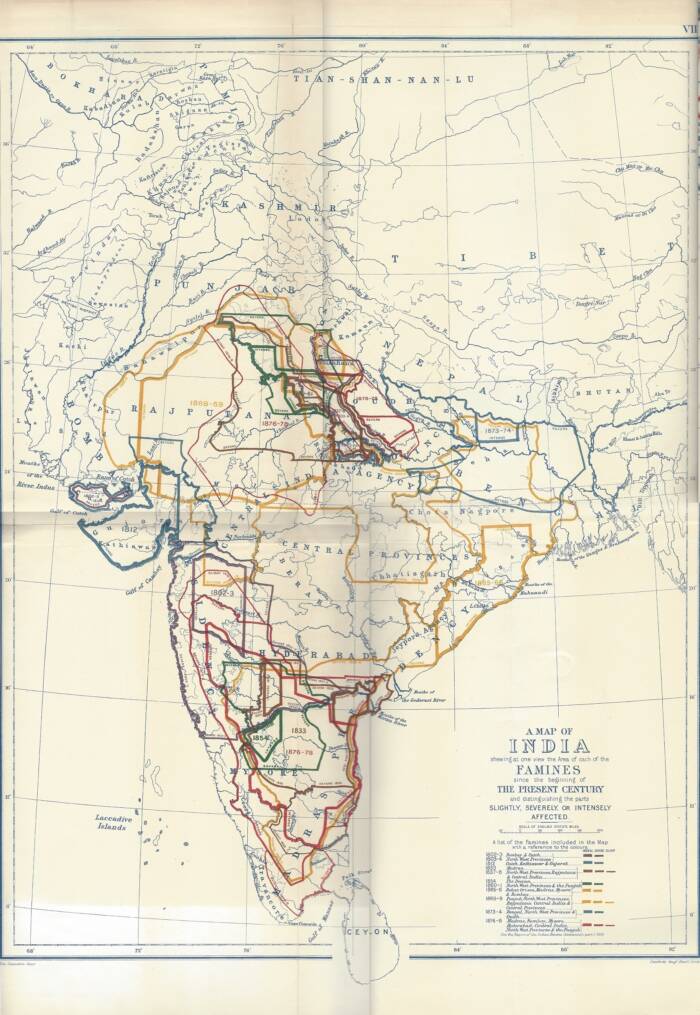

Wikimedia CommonsAn 1885 British map showing the widespread impact of famine in India.

Digby pleaded with other sympathetic Brits to make “impossible in future that such a calamity as this, in which several millions of lives have been sacrificed to hunger and want-induced disease, should occur.”

But unfortunately, Digby’s plea largely fell on deaf ears for a long time. When another serious famine began in India in 1896, the relief offered to the starving public was once again insufficient. And once again, millions died.

Next, learn about the tragic assassination of Mahatma Gandhi, India’s voice for unity. Then, read about the “cursed” Koh-i-Noor diamond from India that eventually became part of England’s Crown Jewels.