Through her sharp treatises and philosophical writings, the self-educated Mary Astell would galvanize the Suffrage movement.

Public DomainJoshua Reynolds’ Study for the Portrait of a Young Woman, often cited (though many say incorrectly) as being a portrait of Mary Astell.

Before there was Gloria Steinem, there was Mary Wollstonecraft, and before there was Mary Wollstonecraft, there was Mary Astell. Though widely unknown today, Mary Astell is credited by many historians as being “the first English feminist” — or proto-feminist, to be precise — to put pen to paper.

Astell wrote with a fierce wit and a keen understanding of the disadvantaged social position of women in her time, primarily due to their lack of education. She led a dangerously independent life for a woman who, as the “fairer sex,” would typically have been shepherded by her father or husband.

Mary Astell would nonetheless become a respected philosopher, pamphleteer, and polemicist in her own right, and she forged a name for herself as a pioneer of feminist thought.

So, read on for a brief overview of the life of Mary Astell, a woman whose influence is anything but.

The Making Of A Feminist, Mary Astell

Mary Astell was born in Newcastle-upon-Tyne in England on Nov. 12, 1666, to a middle-class coal merchant gentry family.

She never received a formal education, which was the sad fate of many girls of Astell’s time. Fortunately, however, she was tutored as a young girl by her clergyman uncle, Ralph Astell, who attended the University of Cambridge during the important philosophical movement known as Cambridge Platonism, an influence clearly seen in Astell’s later work.

Astell’s life took a hard turn when her father died in 1678 when she was 12, leaving her without a dowry and forcing her to live with her mother and aunt. Then her uncle passed just a year later, leaving her in charge of her own education, which she keenly pursued by reading anything she could get her hands on.

Astell’s posthumous 1986 biographer, Ruth Perry, suggested that losing these male figures and coming of age in a small community of women might have been a crucial factor in her feminist outlook.

Mary Astell’s Move To London

By 20 years old, her mother and aunt had both passed away and Astell, an orphan and independent spirit with no prospects for marriage, left for London at 22. This was a decision that was certainly unusual for a young woman of her time.

If she had been a man, possessing the faith and the intelligence that Astell had, she likely would have pursued higher education, become ordained as a priest, and published volumes of sermons. But as a woman, it was not this simple.

Wikimedia CommonsLady Catherine Jones, depicted here as the woman in blue, was one of Mary Astell’s patronesses in Chelsea who helped the feminist’s works to come to fruition.

Soon after Astell arrived in London, she moved to the suburb of Chelsea, which was home to artists, intellectuals, and wealthy families seeking a respite from the London center. She befriended an inner circle of literary scholars, most notably a woman named Lady Catherine Jones, whose household she later joined.

The two women remained close until Astell’s death. One historian describes this friendship as being “close, even passionate, but not, it appears, always a happy one.”

Astell’s Burgeoning Literary Career

After Astell arrived in London, she boldly wrote to William Sancroft, the Archbishop of Canterbury, attaching two volumes of her poetry. She received some assistance from him, and in 1689, she dedicated her earliest writing, A Collection of Poems, to him.

While women of a previous age who wrote for public consumption “forfeited their reputations” and were dismissed as eccentric, sexually loose, or socially unacceptable, Astell actively participated in the blossoming intellectual environment of the early Age of Enlightenment and gained a following among aristocratic women.

Then, in 1693 when Astell was 27 years old, she wrote to an important Cambridge Platonist named John Norris, criticizing one of his theories.

Their hot back-and-forth ended with the esteemed Platonist deeming Astell’s thoughts on his work so impressive that he not only amended his arguments but also later published their correspondence in 1695.

Astell maintained the practice of critiquing prominent male thinkers throughout her writing career. She engaged with and challenged political philosophers of her time such as Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, the Earl of Shaftesbury, Daniel Defoe and Charles D’Avenant.

Crafting Her Literary Canon

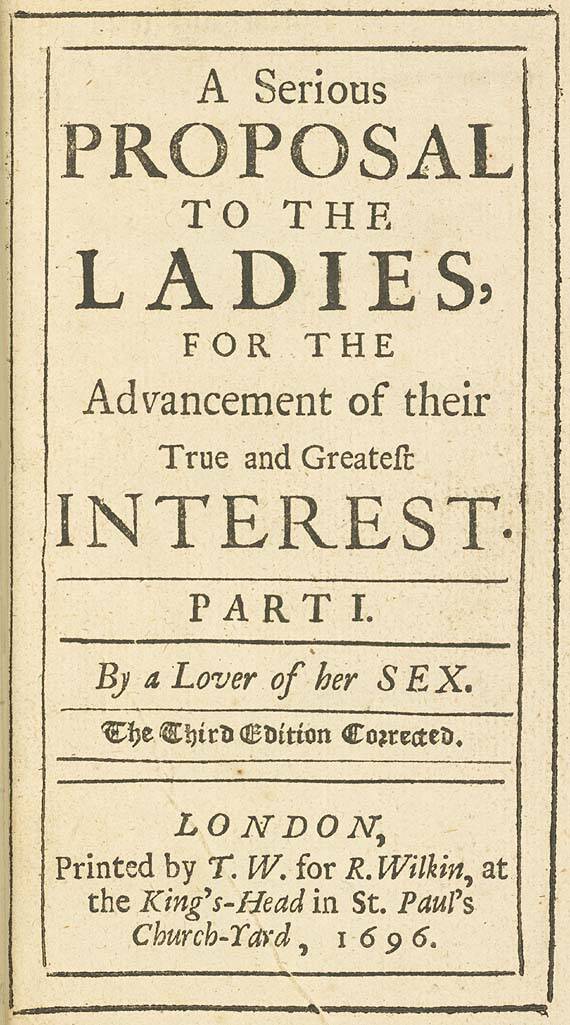

Wikimedia CommonsTitle page from the third edition of 1693’s A Serious Proposal.

While her political and philosophical challenges were celebrated, it would be Astell’s musings on feminism that cemented her place in literary history.

She ultimately wrote six books and two rather long pamphlets discussing education, politics, and religion — all of which feature an underlying feminist agenda and condemn the sad state of women’s education and the resulting ignorance of her sex.

She referred to the role of education in a contemporary woman’s life as reducing her to mere “Tulips in a Garden,” whose usefulness extended only so far as “to make a fine show and be good for nothing.”

Perhaps her most work is her impressive two-part book, A Serious Proposal to the Ladies for the Advancement of their True and Greatest Interest By a Lover of Her Sex, published in 1694 and 1697.

In her Serious Proposal, Astell advocated for a female religious and intellectual community that would provide women with higher education and that would replace the convent, which had been lost to women in England after the Protestant Reformation and Dissolution of the Monasteries in the 1530s.

Despite being a firm Anglican herself, Mary Astell was mocked for suggesting something that sounded like a “protestant nunnery.”

At first, Princess Anne (the future Queen Anne I) was intrigued by the notion of a female educational utopia and considered donating money to support its establishment. But to an England deeply allergic to “popery,” this idea reeked too much of Catholicism and it was never implemented in Astell’s time.

While she was alive, however, Astell led a prolific literary career. In her 1700 book, Some Reflections upon Marriage, Astell urged women to choose a marriage partner more rationally.

“A Woman has no mighty Obligations to the Man who makes Love to her,” Astell argued, “she has no Reason to be fond of being a Wife, or to reckon it a Piece of Preferment when she is taken to be a Man’s Upper-Servant; it is no Advantage to her in this World; if rightly managed it may prove one as to the next.”

In her 1703 An Impartial Inquiry into the Cause of Rebellion and Civil War in This Kingdom, she tackled the complex and controversial political climate of her time, and in her 1705 The Christian Religion, as Professed by a Daughter of the Church of England, she brilliantly championed her beloved Anglican church and argued that a woman’s right to liberty and rationality were given to them by God.

Perhaps most famously, Astell wrote:

“If all men are born free, how is it that women are born slaves? As they must be if the being subjected to the inconstant, uncertain, unknown, arbitrary Will of Men, be the perfect Condition of Slavery?”

Her Final Years

Wikimedia CommonsJohn Locke, one of the prominent male thinkers of Mary Astell’s time, of whom the feminist had many critiques.

In her later years, Mary Astell retired from writing and joined forces with her good friend Lady Catherine and several other women to found a charity school for girls in Chelsea in 1709.

The combination of this girls’ school, her own studies, and her faith kept her busy until the final days. In May 1731, Astell died from breast cancer, after undergoing a painful mastectomy. She allegedly spent her final days in voluntary isolation in a room beside her own coffin.

After her death, Mary Astell was celebrated for her literary achievements. She was well-known amongst the political and philosophical circles of the day and was read by important male figures who had the position to perpetuate her works.

Some scholars have even gone so far as to say that she influenced Samuel Richardson’s literary masterpiece, Clarissa. Her feminist ideologies had particularly strong reverberations among women who applauded and imitated Astell in their own writings for generations to come.

Her name largely slips under the radar in favor of more modern feminist writers, and those who do study Astell’s work these days often lose sight of the historical context in which she existed and understand her zealous faith and conservative political positions to be antithetical to feminism.

However, her writing remains important in the study of women’s rights, Enlightenment philosophy, and early modern religious and political thought. Mary Astell deserves recognition for her work in championing women’s God-given right to education and liberty.

After this look at the mother of all feminists, Mary Astell, check out these 50 moving photos from the women’s suffrage movement. Then, read up on these six feminist icons who don’t get enough credit.