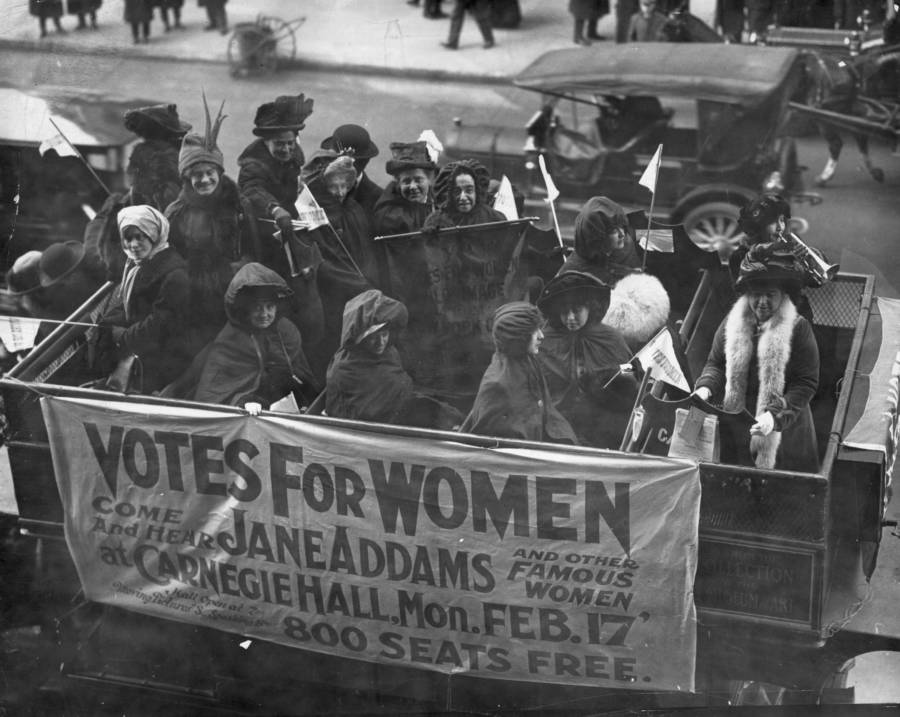

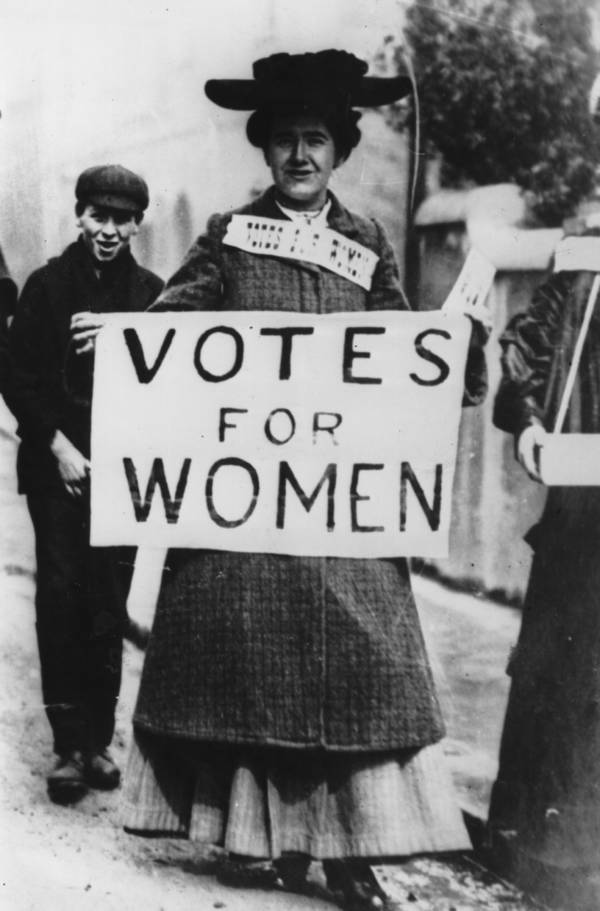

For nearly a century, women's suffragists battled misogyny, violence, and even each other in their fight to pass the 19th Amendment and win women's right to vote.

On Aug. 18, 1920, American women won the right to vote thanks to the ratification of the 19th Amendment. Though this historic moment is celebrated today, it was a controversial decision at the time. Women’s suffrage had been a century-long struggle — and men had resisted the idea since the early days of the country.

Records show that women floated the idea of suffrage as far back as 1776. As America’s founding fathers discussed how to organize the leadership of their new nation, Abigail Adams wrote to her husband John Adams, who would be the second president of the United States:

“In the new code of laws which I suppose it will be necessary for you to make, I desire you would remember the ladies and be more generous and favorable to them than your ancestors. Do not put such unlimited power into the hands of the husbands.”

“Remember, all men would be tyrants if they could. If particular care and attention is not paid to the ladies, we are determined to foment a rebellion, and will not hold ourselves bound by any laws in which we have no voice or representation.”

She was ignored. But the “rebellion” that she foreshadowed did come — and it culminated when American women won the right to vote.

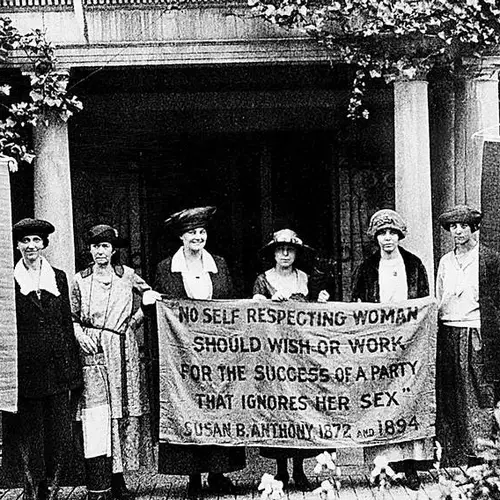

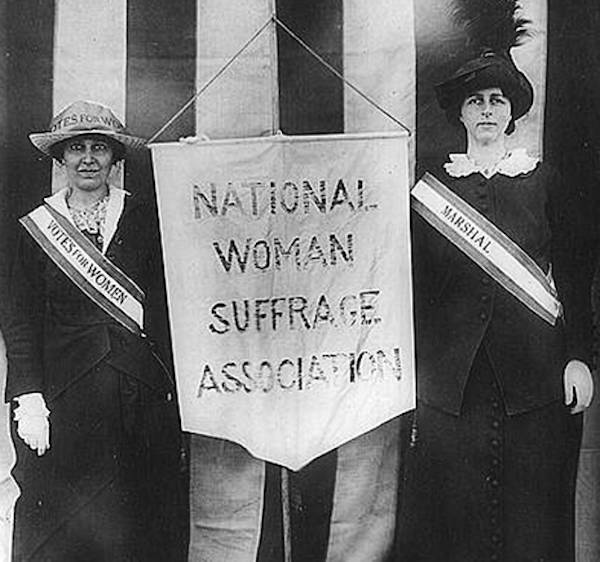

Wikimedia CommonsAmerican suffragists, Mrs. Stanley McCormick and Mrs. Charles Parker, stand in solidarity for their organization. April 22, 1913.

The right to vote meant the right to an opinion and the right to a voice, which were two virtues that women were historically denied. But the ratification of the 19th Amendment to the Constitution of the United States symbolized an end to the institutionalized silencing of women.

At its zenith, the women’s suffrage movement numbered 2 million supporters, all at the expense of their families and reputations. And at times, suffragists had to fight against other women who opposed their cause.

Despite these hurdles, 100 years have now passed since the ratification of the 19th Amendment. As we commemorate this American milestone, let’s explore how it came to be. As it turns out, the women’s suffrage movement has roots in another cause for human rights: abolition.

Many Early Suffragists Were Also Abolitionists

Wikimedia CommonsElizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony.

Many of the nation’s most famous suffragists, including Lucretia Mott and Susan B. Anthony, were also steadfast abolitionists as both movements sought to expand American equality. Moreover, many suffragists were also religious and opposed slavery and the oppression of women for the same moral reasons.

The anti-slavery movement also gave outspoken female activists an opportunity to hone their skills in protest. Because women were often excluded from discussions about the future of the country, they were forced to hold their own forums.

For example, in 1833, Lucretia Mott helped found the Female Anti-Slavery Society, which had both Black and white women in leadership roles. And when both Mott and Stanton were excluded from attending the World Anti-Slavery Convention in London in 1840, they resolved to form their own convention.

By the 1820s and ’30s, most states in America had ensured a white man’s right to vote. Even though some states still required that men reach specific qualifications concerning wealth or land ownership, for the most part, white men who were U.S. citizens could participate in the democratic process. Women were all too aware that the right to vote was becoming more inclusive.

While trying to earn the rights of others, a fertile ground had been laid for the suffrage movement. Unfortunately, this movement would become divided on the basis of class and race.

The Seneca Falls Convention And Opposition From Other Women

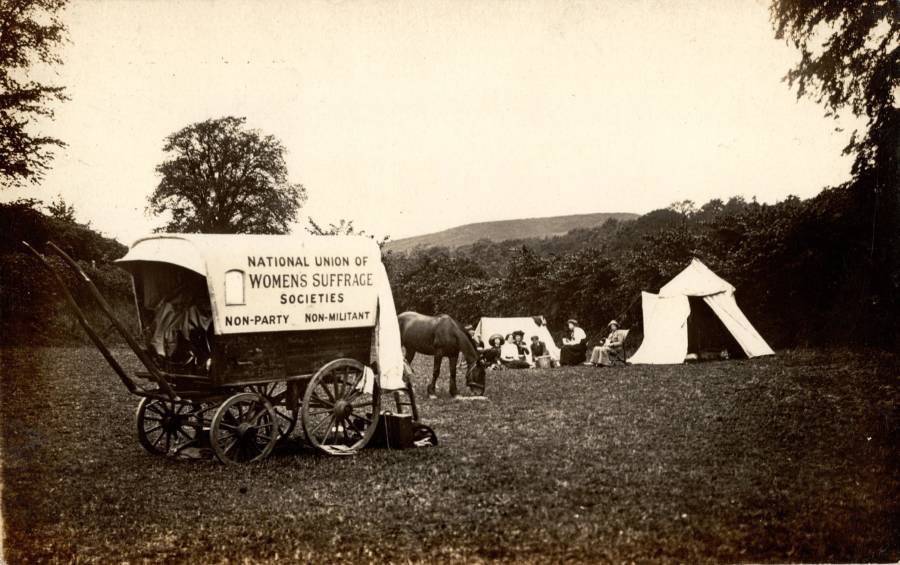

Wikimedia CommonsSuffragists at a pageant by the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies. June 1908.

In 1848, Stanton and Mott held the first convention dedicated to the ratification of women’s suffrage in Seneca Falls, New York. About 100 people attended, two-thirds of them women. However, some Black male abolitionists also made an appearance, including Frederick Douglass.

At this point in America, married women had no right to property or ownership of their wages, and the mere concept of casting ballots was so unfamiliar to many of them that even those attending the convention had difficulty processing the idea.

The Seneca Falls Convention nonetheless ended in a vital precedent: the Declaration of Sentiments.

“We hold these truths to be self-evident,” the Declaration read, “that all men and women are created equal, that they are endowed by their creator with certain inalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

The meeting saw unanimous support for the issue of women’s right to vote and passed resolutions to support a woman’s right to her own wages, to divorce abusive husbands, and to have representation in government. But all this progress would be momentarily hampered by an impending war.

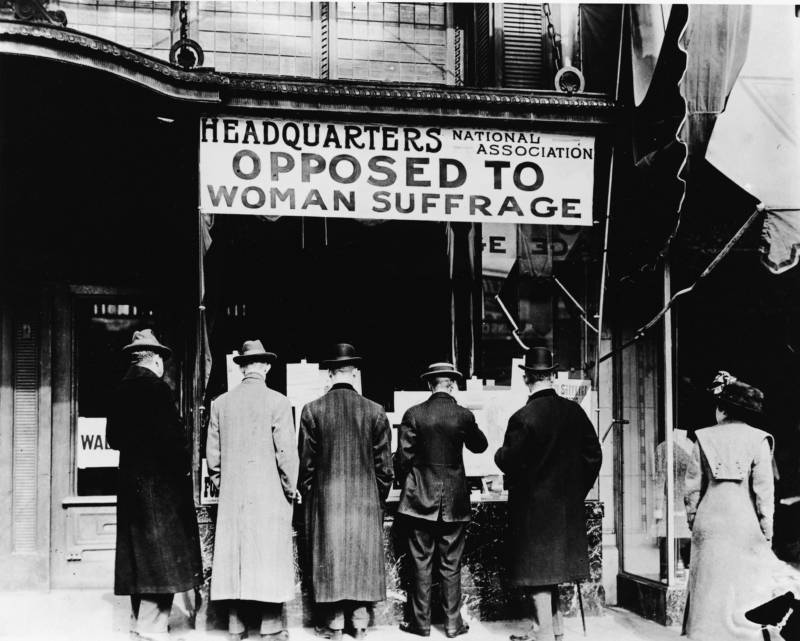

The movement was also in part stalled by other women as early as the 1870s. In 1911, these so-called anti-suffragists formed an outspoken organization called the National Association Opposed to Women’s Suffrage (NAOWS), which threatened the movement’s progress.

Anti-suffragists were from all walks of life. They included beer brewers, Catholic women, Democrats, and factory owners that used child labor. But they all seemed to believe that the order of the American family would collapse if women got the right to vote.

The organization claimed to have 350,000 members who feared that women’s suffrage “would reduce the special protections and routes of influence available to women, destroy the family, and increase the number of socialist-leaning voters.”

Racial Divisions In The Suffrage Movement

Wikimedia CommonsA National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies camper, parked at Kineton in Warwickshire en route to London. 1913.

As history is not entirely without a sense of irony, the beginning of the Civil War saw a radical shift in focus from women’s rights to the rights of slaves. Women’s suffrage lost steam and even white suffragists who began in the abolition movement returned to the issue of racial division.

It was the “Negro’s hour,” as white abolitionist Wendell Phillips proclaimed. He urged women to stand back while the fight to liberate slaves gained increasing attention. Despite this proclamation, Black women remained the most overlooked demographic in the U.S.

In 1869, Stanton and Mott tried, unsuccessfully, to include women in the provisions of the 15th Amendment, which gave freed Black men the right to vote. Racial division continued to form in the suffragist movement as Stanton and Mott opposed the 15th Amendment on the basis that it excluded women.

Wikimedia CommonsSuffragists parade down New York City’s Fifth Avenue displaying placards containing the signatures of more than 1 million New York women to advocate for women’s rights. October 1917.

In response, another suffragist named Lucy Stone formed a competing women’s rights organization that demonized Stanton and Mott for being racially divisive. This group also sought to achieve women’s suffrage state by state, rather than on a federal level, as Stanton and Mott desired.

In 1890, Stanton, Mott, and Stone managed to combine forces to create the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). While this organization did not exclude Black women on the national level, local factions could and did decide to exclude them.

Wikimedia CommonsIda B. Wells, a Black suffragist and investigative reporter.

Around this time, Black suffragists like Ida B. Wells-Barnett and Mary Church Terrell confronted white suffragists on the issue of Black men being lynched in America. This made Wells-Barnett somewhat unpopular in mainstream American suffragist circles, but she nonetheless helped to found the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs.

Militant Suffragists Enter The Fray

In 1869, over 20 years after the first official meeting in Seneca Falls, Wyoming passed the first law in the U.S. that gave women the right to vote and to hold office. Though Wyoming was not yet a state, it pledged not to revoke women's suffrage when it was asked to the join the Union. In 1890, when it did become an official state, women there still had the right to vote.

But the war for women's right to vote was not over.

Middle-class women who were members of women's clubs or societies, temperance advocates, and participants in local civic and charity organizations joined in the movement, giving it new life.

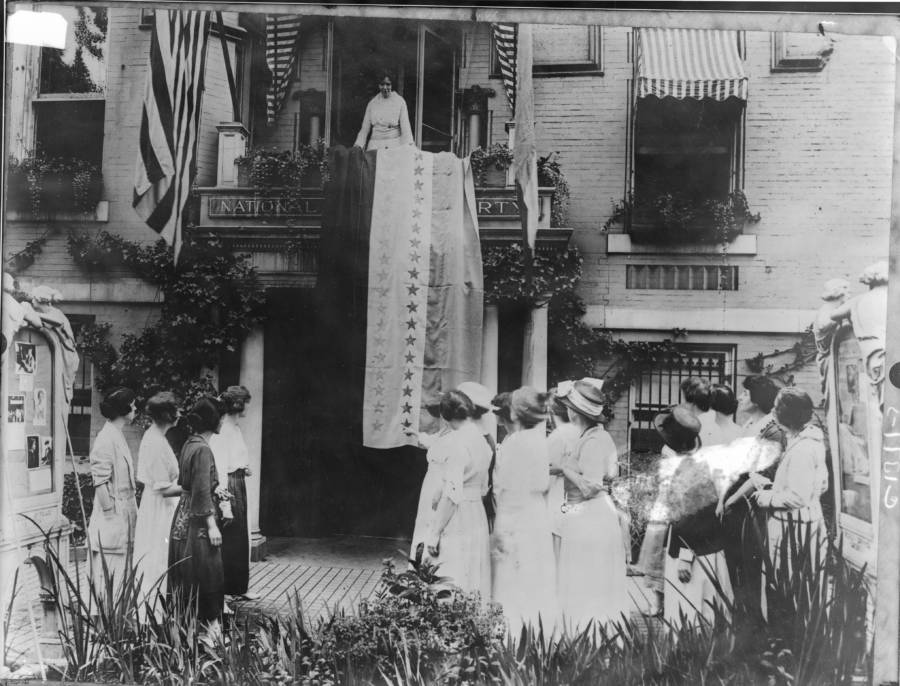

Around this time, yet another faction of suffragists appeared. These were young radical women who were impatient with the pace of the women's suffrage movement thus far. These women, led by college graduate Alice Paul, opted for militant strategies like those used by suffragist Emmeline Pankhurst in England at the same time. Pankhurst was known for her hunger strikes and for throwing bricks at the windows of Parliament.

National Museum Of American HistoryActivist Alice Paul protests outside the Republican National Convention in Chicago in June 1920.

In 1913, Paul orchestrated a parade of 5,000 people on Washington D.C.'s Pennsylvania Avenue. The parade was well planned, as tens of thousands of onlookers were already gathered there for Woodrow Wilson's presidential inauguration the following day.

"No one had ever claimed the street for a protest march like this one," wrote Rebecca Boggs Roberts in Suffragettes in Washington, D.C.: The 1913 Parade and the Fight for the Vote. However, the march was segregated.

Paul attracted a crowd of younger and more educated women and encouraged them to fearlessly protest Wilson's administration.

In fact, during President Wilson's second inauguration four years later, hundreds of suffragists led by Paul picketed outside the White House. Seeing a dedicated group of ambitious young women brave the freezing rain was "a sight to impress even the jaded senses of one who has seen much," a correspondent wrote.

Unfortunately, almost 100 protesters were arrested for reasons like "obstructing sidewalk traffic" that day. After being taken to a workhouse in Virginia or the District of Columbia jail, many of them initiated a hunger strike. Subsequently, they were force-fed by the police via tubes shoved up their noses.

"Miss Paul vomits much. I do too," one of the inmates, Rose Winslow, wrote. "We think of the coming feeding all day. It is horrible."

The Ratification Of The 19th Amendment

Wikimedia CommonsSuffragists march down the streets in 1913.

In 1915, a veteran suffragist named Carrie Chapman Catt took the helm as the president of NAWSA. It was her second time in the position and it would be her most monumental. By this time, NAWSA had 44 state chapters and more than 2 million members.

Catt devised a "Winning Plan," which mandated that women in states where they could already vote for president would focus on passing a federal suffrage amendment while women who believed they could influence their state legislatures would focus on amending their state constitutions. At the same time, NAWSA worked to elect congressmen who supported women's suffrage.

However, yet another war encroached on the women's suffrage movement: World War I. This time, the movement found a way to capitalize on Woodrow Wilson's decision to enter the global conflict. They argued that if America wanted to create a more just and equitable world abroad, then the country should begin by giving half of its population the right to a political voice.

Catt was so confident that the plan would work that she founded the League of Women Voters before the amendment even passed.

Wikimedia CommonsCatt was head of NAWSA when the 19th Amendment was ratified.

Then, the women's suffrage movement made a giant leap forward in 1916 when Jeannette Rankin became the first woman elected to Congress in Montana. She boldly opened up the discussion around Susan B. Anthony's proposed amendment (aptly nicknamed the Susan B. Anthony Amendment) to the Constitution that asserted that states could not discriminate on the basis of sex in regard to the right to vote.

By that same year, 15 states had granted women the right to vote and Woodrow Wilson fully supported Susan B. Anthony's Amendment. Between January 1918 and June 1919, Congress voted on the federal amendment five times. Finally, on June 4, 1919, the amendment was brought before the Senate. Ultimately, 76 percent of Republican senators voted in favor, while 60 percent of Democrat senators voted against.

NAWSA now had to pressure at least 36 states by November 1920 to adopt the amendment in order for it to be officially written into the Constitution.

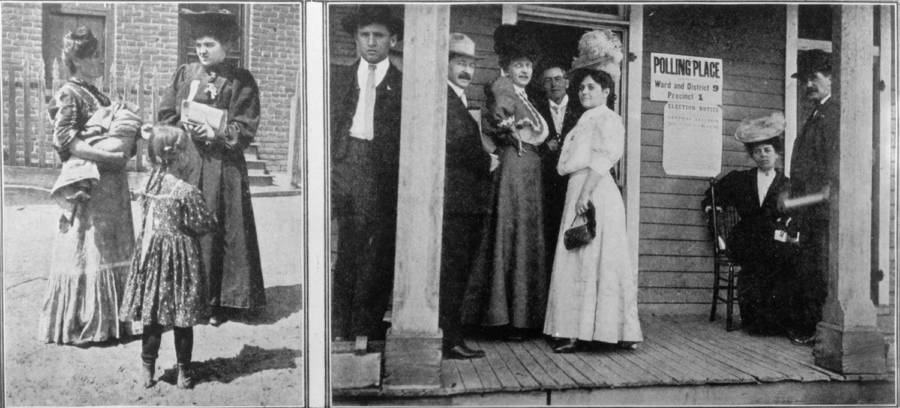

Wikimedia CommonsBoth men and women lined up outside a Colorado polling station. 1893.

On Aug. 18, 1920, Tennessee became the 36th state to ratify Susan B. Anthony's Amendment. The 19th Amendment became law eight days later.

The Fight For Voter Equality Continues

Wikimedia CommonsMembers of the Church League for Women's Suffrage proceed down the street in droves.

In 1923, a group of suffragists proposed an amendment to the Constitution that prohibited all discrimination on the basis of sex, but this Equal Rights Amendment has never been ratified, which means that there is no nationwide law that ensures equal voting rights for all Americans.

Since then, two more amendments have been ratified in order to expand America's voting rights. The 24th Amendment was passed in 1964 and prohibited the use of poll fees. Up until that point, some states charged their citizens a fee in order to enter the polls, which excluded anyone unable to pay that fee from participating in their civic duty.

The 26th Amendment mandated that anyone 18 or older was eligible to vote. This amendment was born largely out of the notion that citizens who were old enough to drafted into war ought to be allowed to decide who is sending them to that war.

Today, gerrymandering, voter ID laws, and strict polling times continue to prevent large portions of the country from casting their ballot. But that certainly hasn't stopped voting rights activists from fighting back.

"Coretta Scott King once said that struggle is a never ending process. Freedom is never really won," said Mary Pat Hector, the youth director of the National Action Network. "You win it and earn it in every generation, and I believe that it's always gonna be a constant fight and it's gonna be a constant struggle."

"But I believe that we have the generation that's willing to say, 'I'm prepared to fight.'"

After experiencing the women's suffrage movement through these inspiring photos, meet the feminist icons who don't get the credit they deserve. Then take a look at some of the most sexist ads that ever saw the light of day.