To create lasting change--regardless of the area--it takes consistent, joint efforts. The same can be said about the Suffrage Movement.

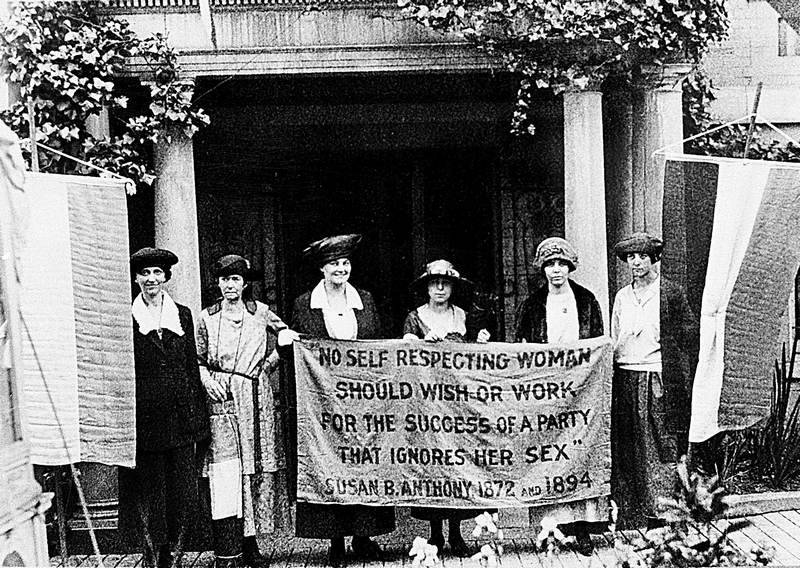

National Woman’s Party officers gather for the 1920 Republican National Convention to fight for ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment.

Many influential women in the suffrage movement paved the way for the Nineteenth Amendment, which became law on August 18, 1920.

Women’s Suffrage Leaders: Abigail Adams

Back in 1776, Abigail Adams sent a letter to her husband, John Adams, who would later become America’s second president. At the time, he was attending the Continental Congress, where wealthy colonists, all men, were deciding whether or not to declare independence from Great Britain.

In the letter, Abigail urges him to allow women a place in the new nation’s government. Yet all the talk of “Oppressions…abuses and usurpations” in the Declaration of Independence did nothing to change the position of women, who were left with few rights, or that of slaves, who had none. It was an inherently unequal society ironically built on the concept of equality.

A young Abigail Adams. Source: About

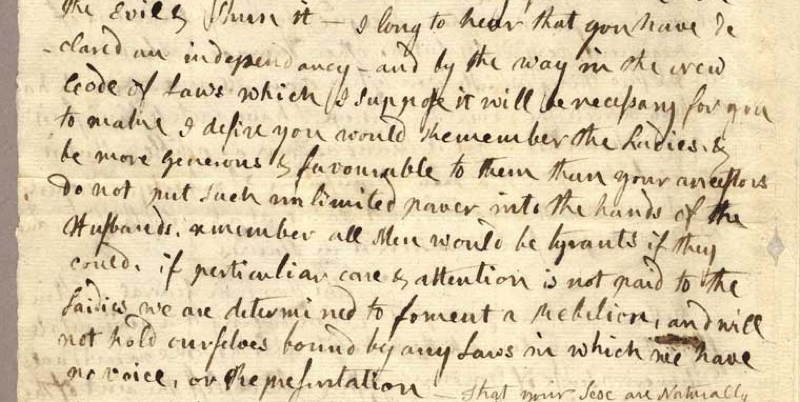

In that letter to John, Abigail wrote:

“…in the new code of laws which I suppose it will be necessary for you to make, I desire you would remember the ladies and be more generous and favorable to them than your ancestors. Do not put such unlimited power into the hands of the husbands. Remember, all men would be tyrants if they could. If particular care and attention is not paid to the ladies, we are determined to foment a rebellion, and will not hold ourselves bound by any laws in which we have no voice or representation.”

The actual section of that letter from Abigail Adams to her husband John. Source: Vassar

Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Alas, women couldn’t vote for another century and a half.

A major force in the women’s suffrage movement, Susan B. Anthony, was pretty hardcore–she was once arrested for voting. She also fought for abolition of slavery before the Civil War. Later, she faced jeers and mobs when she dared to suggest that the newly freed blacks should have the right to do anything a white citizen could do.

Anthony partnered with Elizabeth Cady Stanton for much of their lives. They fought for the abolition of slavery, temperance, and women’s rights. Anthony had the public-speaking prowess while Stanton had the writing ability.

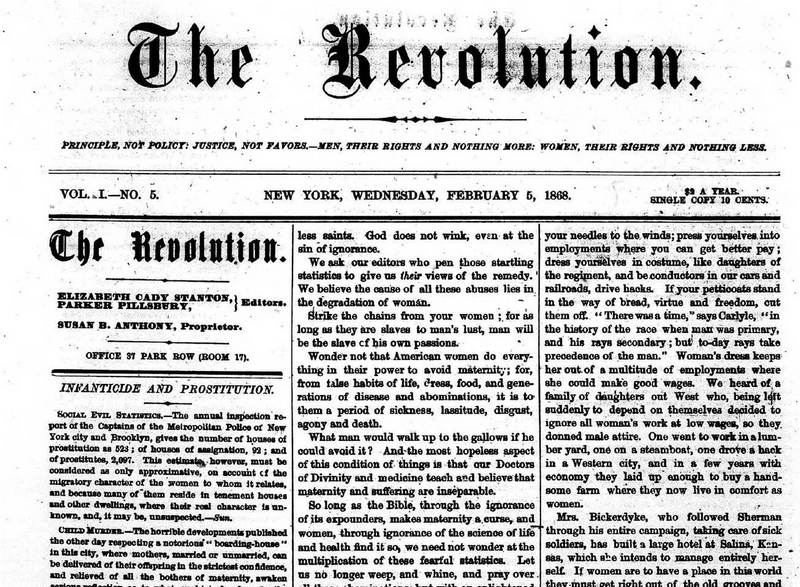

Anthony is better known today, but quotes that are attributed to her were often from speeches that Stanton wrote. Together, they built the foundation for the women’s suffrage movement. The weekly newspaper they founded, The Revolution, trumpeted their goal in its masthead: “Men, their rights and nothing more; women, their rights and nothing less.”

Stanton is also notable because when she married in 1840, she refused to be known as Mrs. Henry Stanton. “I have very serious objections…to being called Henry. Ask our colored brethren if there’s nothing to a name. Why are the slaves nameless unless they take that of their master? Simply because they have no independent existence. They are mere chattels, with no civil or social rights.”

It can be jarring enough to take a new last name, but to lose one’s first name as well is like stripping off a piece of a woman’s skin and slapping on a sticker featuring her husband’s smiling face to cover the wound. It wipes out a woman’s identity. Elizabeth Cady Stanton wasn’t willing to be erased.

Lucretia Mott

Source: Meetville

An abolitionist, Lucretia Mott met Stanton at the World Anti-Slavery Convention in London in 1840. They were excluded from participation at the event and were both good and mad about it, so they came up with the idea of the First Woman’s Rights Convention.

In The History of Women Suffrage, Stanton remembered:

“the men to whom [Mott and Stanton] had just listened had manifested their great need of some education on that question. Thus a missionary work for the emancipation of woman…was then and there inaugurated.”

Carrie Chapman Catt

Source: YouTube

As the leader of the National American Women’s Suffrage Association, Carrie Chapman Catt came up with the “Winning Plan,” a campaigning strategy that secured a constitutional amendment granting women the right to vote.

She was so confident that the plan would work that she founded the League of Women Voters before the amendment even passed.

Lucy Burns and Alice Paul

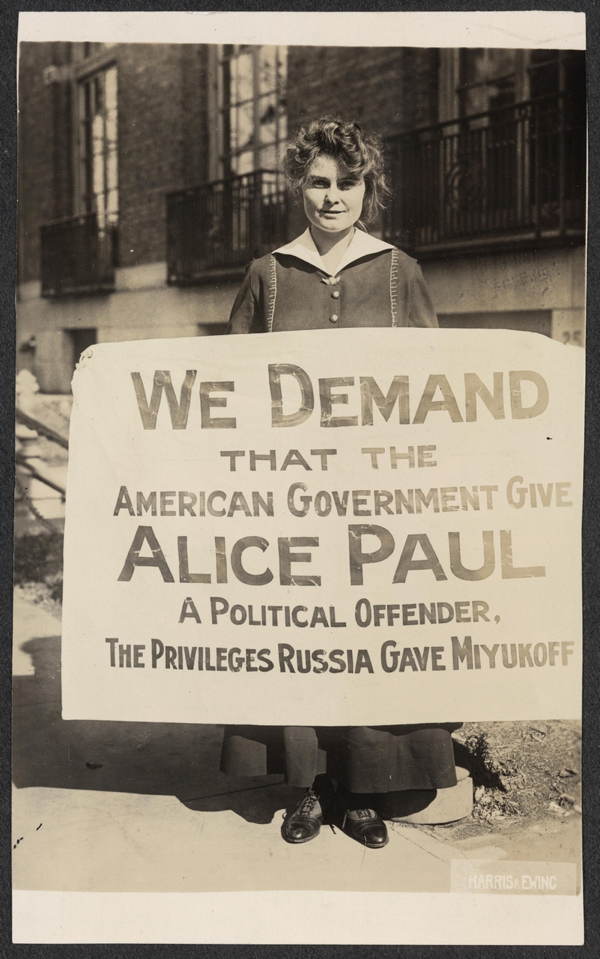

Lucy Burns has a dubious distinction; she was the suffragist who spent the most time in prison. More militant than Anthony, Stanton, or Catt, Burns was arrested at demonstrations time and again. In prison, she led hunger strikes and was force-fed. Along with Alice Paul, she founded the National Woman’s Party (NWP).

A suffragist protests the treatment of Alice Paul in prison. Source: LOC

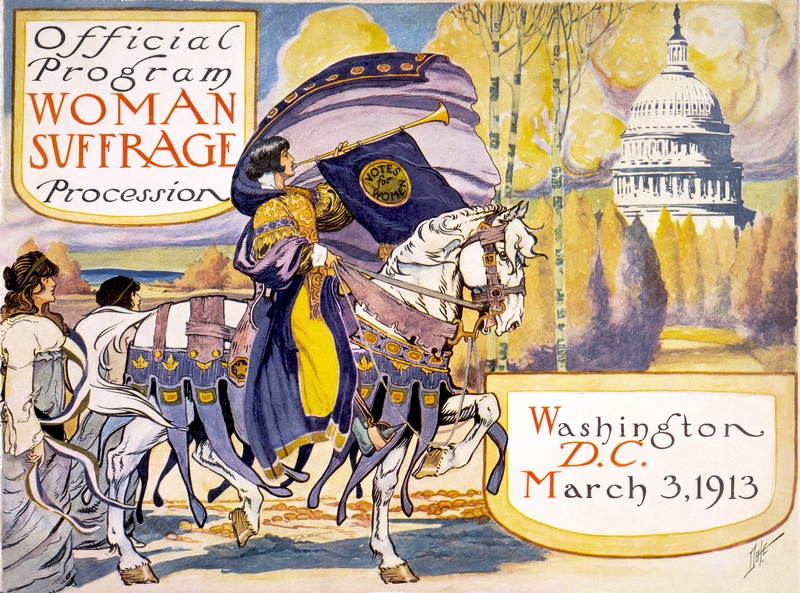

Alice Paul was probably the most educated of the leaders of the women’s suffrage movement. She earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees, a PhD, as well as three law degrees. She also gained experience in militant suffragist actions while studying in Britain. Back home, she organized the largest women’s suffrage parade in Washington, D.C. in 1913.

Source: Wikipedia

But this didn’t make a dent in the opinions of Congress or president Woodrow Wilson. So, in 1917, Paul joined a group of women that became the first ever to picket the White House.

Over 18 months, they became known as the Silent Sentinels; they wordlessly strode back and forth, holding signs with slogans like, “Mr. President, how long must women wait for liberty?”

They were arrested over and over again, and given longer and longer sentences. Paul was also force-fed in prison when she attempted a hunger strike. Less than two years later, women were finally granted the right to vote.

The Silent Sentinels picket the White House.