Mount Tambora's eruption on April 10, 1815, was so powerful that it was heard 1,600 miles away, while its massive ash cloud covered the Sun and caused global temperatures to drop five degrees.

NASAMount Tambora seen today from above, with the massive caldera that formed during the 1815 eruption.

The Mount Tambora eruption in April 1815 was the most powerful volcanic blast in recorded human history. The stratovolcano on the Indonesian island of Sumbawa had been dormant for centuries — and then it suddenly exploded, sparking a worldwide disaster that ultimately killed hundreds of thousands of people.

The eruption was so ferocious that it caused Mount Tambora to lose more than 4,000 feet in height, collapsing into a caldera about 3.7 miles wide. Nearby villages on Sumbawa and the neighboring Lombok were, in an instant, incinerated, buried under ash, or swept away by tsunamis. An estimated 10,000 people living on the island were killed immediately as a result.

Some 24 cubic miles of gasses, dust, and rock were thrown into the atmosphere during the eruption. The lingering effects across the Northern Hemisphere caused cold temperatures throughout the summer of 1816, which subsequently resulted in crop failures and famine and led to 1816 becoming known as “The Year Without a Summer.”

But while the 1815 Mount Tambora eruption had devastating consequences for the environment and agriculture, it had a surprisingly beneficial impact on the world of literature. Because of the grim weather in Switzerland during the summer of 1816, a group of authors trapped indoors decided to have a writing contest. Those writers were Mary Shelley, her husband Percy Bysshe Shelley, and fellow poet Lord Byron.

It was during this period that Mary Shelley wrote Frankenstein and Lord Byron penned the poem “Darkness,” which begins, “I had a dream, which was not at all a dream. The bright sun was extinguish’d.”

The Most Destructive Volcanic Eruption In Recorded History

Georesearch Volcanedo Germany/Wikimedia CommonsThe floor of Mount Tambora’s caldera, which is more than three miles wide.

The first sign that something was wrong with Mount Tambora came on April 5, 1815, just as the sun began to set. There was a sudden explosion, and a plume of ash burst 18 miles upward into the sky. Lava streamed from the mountain’s peak for more than two hours.

After centuries of dormancy, the volcano had awoken. And it was just getting started.

Elsewhere, hundreds of miles away, reports of thunderous detonation sounds flooded in. As authors William and Nicholas Klingaman wrote in an excerpt from The Year Without Summer, “Thomas Stamford Raffles, the lieutenant-governor of Java, heard the blast at his residence and assumed it came from cannon firing in the distance. Other British authorities on the island made the same mistake.”

Europe was nearing the end of the Napoleonic Wars, so it was perhaps understandable that British authorities mistook the loud boom as a potential attack from their enemies. The telegraph had yet to be invented; information traveled slowly. But the Indonesian islanders, who were more accustomed to the Earth’s violent shakings, may have suspected what was yet to come.

Public DomainWilliam Sadler II’s depiction of the pivotal Battle of Waterloo in 1815.

A day after the initial burst, ash began to fall in East Java, and frequent, faint detonation sounds were heard for four more days. Similar sounds were being reported in locations like Sumatra, 1,600 miles away, and potentially as far as Vientiane, 2,072 miles away. The cloud of ash and debris was so thick that the world’s climate cooled by roughly 5.4 degrees Fahrenheit.

Then, on April 10, bits of sunlight began to poke through the clouds. The explosions had quieted. All, it seemed, was well.

Suddenly, around 7 p.m., the eruptions intensified. As Raffles described in his memoir, Mount Tambora had, in an instant, become a mass of “liquid fire.” Eight-inch pumice stones rained down on the island, and soon, a violent whirlwind emerged, tearing through entire villages and forests with ease. The villages of Saugur and Tambora were wiped out entirely.

An estimated 10,000 people living on the island were killed in the immediate eruption. The blast itself was 10 times more powerful than the more widely known eruption of Krakatoa, with a volcanic explosivity index (VEI) of seven out of a possible eight.

Smaller eruptions continued for the next six months, with some reports suggesting they went on for another three years. But even though the climax of the eruption occurred on April 10, the lingering effects would affect far more than just the Indonesian islands.

1816: The Year Without A Summer

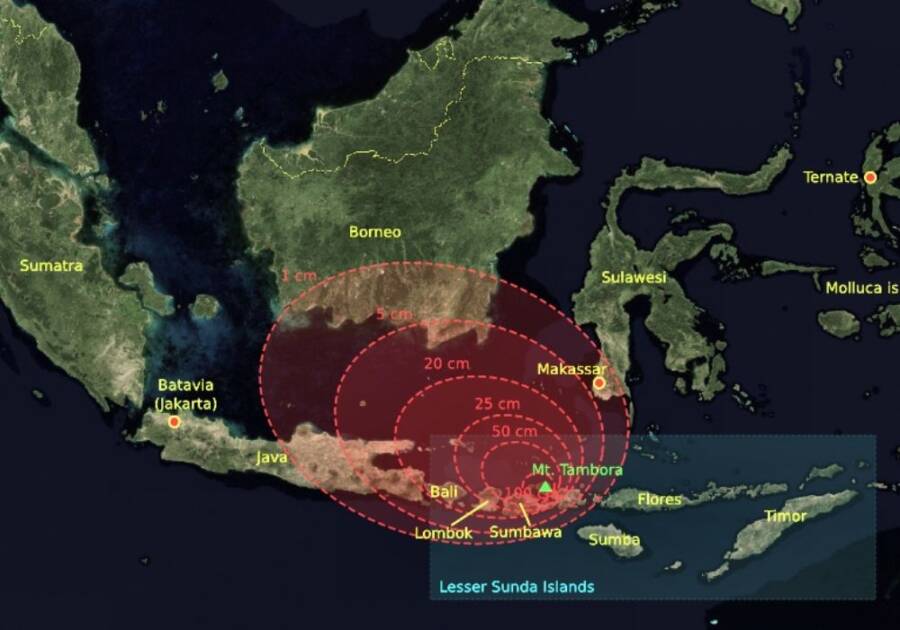

Indon/NASA/Wikimedia CommonsThe blast radius of the 1815 Mount Tambora eruption.

Small ash particles lingered in the stratosphere following the eruption, blocking solar radiation and absorbing heat. The result was the most devastating period of extreme weather seen in thousands of years. As such, the summer of 1816, which should have been a warm time in the Northern Hemisphere, was instead a cold, dreary, volcanic winter.

The effects were especially brutal in Europe, where the fallout of the Napoleonic Wars was still being felt. The bitter cold and snowfall caused substantial crop failures, making food scarce. Ireland, in particular, suffered from famine due to an inability to grow wheat, oat, and potato crops. Civil unrest was rampant, and a typhus outbreak only compounded the devastation. An estimated 40,000 people died as a result.

The United States felt the impact, too, albeit to a lesser degree. Snowfall and frozen soil persisted into the summer, making it more difficult to grow crops and causing prices to skyrocket. Seeking warmer climates and better farmland, many farmers in New England and elsewhere along the East Coast were forced to move west.

These conditions subsequently led to the first major economic depression in U.S. history, the Panic of 1819, as harvests finally stabilized in Europe and U.S. grain exports were no longer relied upon.

There were, however, several surprising outcomes from this bleak time period.

The Consequences Of The Mount Tambora Eruption Around The World

Public DomainCrossing the Brook by J. M. W. Turner, painted during the summer of 1815 when the dust and debris from Mount Tambora cast the skies around the world in a foggy yellow hue.

According to the Center for Science Education at the University Corporation for Atmospheric Research (UCAR), the increased cost of oats — and, therefore, the increased cost of traveling via horseback — may have partly inspired German engineer Karl Drais to devise the bicycle as an alternative method of transportation. And Drais wasn’t alone in his innovation.

The shockingly cold and dreary summer weather just so happened to coincide with a vacation to Lake Geneva taken by Mary Shelley, her husband Percy Bysshe Shelley, and the poet Lord Byron. Trapped inside during a storm, the three issued a writing challenge to one another and drew direct inspiration from the circumstances.

Lord Byron penned the poem “Darkness” during this time, and Mary Shelley wrote Frankenstein, forever changing the literary world.

There is a reason, after all, that many horror stories still begin “on a dark and stormy night.”

Public DomainMary Shelley, the author who penned Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus during the summer of 1816.

Lasting damage from the explosion and subsequent climate change wasn’t limited to the Western world, though. The Bay of Bengal east of the Indian subcontinent was severely impacted as the changing environment altered the ecology of the bay and led to the mutation of Bengal cholera, which spread quickly and killed tens of millions in a global pandemic lasting until 1823.

The Yunnan province of China also suffered a three-year famine due to flooding and cold weather in the growing season after a disruption to the usual monsoon season. As a response, many farmers turned to growing poppies as they were more resilient — and this caused Yunnan to become a major producer of opium for the rest of the world.

The Chinese writer Li Yuyang similarly took inspiration from the troubled times and revived the poetry of seven sorrows, an ancient Chinese style that used the senses to describe injustice and tragedy.

Artists such as J. M. W. Turner and Caspar David Friedrich likewise incorporated elements of this Sunless summer into their works, depicting the yellow, cloud-filled skies that were common following Mount Tambora’s eruption. Given that this was a time well before color photography, their works are some of the closest representations of what the Year Without a Summer looked like — and it was both beautiful and haunting.

Of course, not every hardship that arose during the late 1810s could be solely blamed on the Mount Tambora eruption. Certain trends had already been underway, but the blast most certainly exacerbated global problems and, more importantly, highlighted just how devastating a sudden shift in climate and weather extremes can be.

Even today, Mount Tambora is a fascinating case study of the unpredictability of nature and the catastrophic outcomes it can cause.

After reading about the 1815 Mount Tambora eruption and the tumultuous times that followed, go inside the Mount Vesuvius eruption that destroyed Pompeii in 79 C.E. Then, see the dramatic before and after photos of the Mount St. Helens eruption.