After years of aggressive phosphate mining, poor investments, rampant corruption, and an increasingly turbulent economy, Nauru is one of the most difficult places to live on Earth.

Public DomainNauru, as seen from above.

In 1798, a British sea captain spotted a speck of land while sailing in the South Pacific Ocean. He dubbed it “Pleasant Island.” But today, the island is known as Nauru. It’s the third-smallest country in the world — larger only than Vatican City and Monaco — and the world’s smallest island nation.

So what’s it like?

This is the story of Nauru, from its unique geography, to its turbulent history, to the many challenges of living on the island today.

A Tiny Island In The South Pacific

Located in the South Pacific Ocean, 26 miles south of the equator and about 2,500 miles from Australia, Nauru is an oval-shaped island with an area of just over eight square miles. From the sky, it appears as flat as the ocean.

d-online/Wikimedia CommonsCoral pillars rising off the coast of Nauru, the world’s smallest island country.

Lacking natural harbors, the Micronesian island is surrounded by coral reefs, and one of its most defining features are its coral cliffs, which rise dozens of feet above sea level. Though much of the island is inhospitable to crops, Nauru does have a fertile strip of land where bananas, pineapples, coconut palms, and some vegetables are able to successfully grow.

While crops might not grow easily on most of the island, Nauru has a tropical climate with temperatures in the 80s (Fahrenheit). It also has an annual rainfall of about 80 inches a year, but the weather can be unpredictable, and Nauru can also suffer from periods of drought.

Despite the challenges with agriculture and the somewhat volatile weather conditions, about 12,000 people call Nauru home. Most residents are Indigenous Nauruans who have lived on the island their whole lives.

The People Of Nauru And The Island’s History

The history of Nauru stretches back thousands of years. Archaeologists believe that the island was first settled by Micronesian and Polynesian settlers by around 1000 B.C.E., and that their long isolation from other cultures is the reason behind the uniqueness of the Nauruan language.

Over the centuries, Nauruans developed a matrilineal society, divided into 12 clans. These clans co-existed somewhat peacefully until the 19th century, when Europeans started to arrive more frequently on the island’s shores.

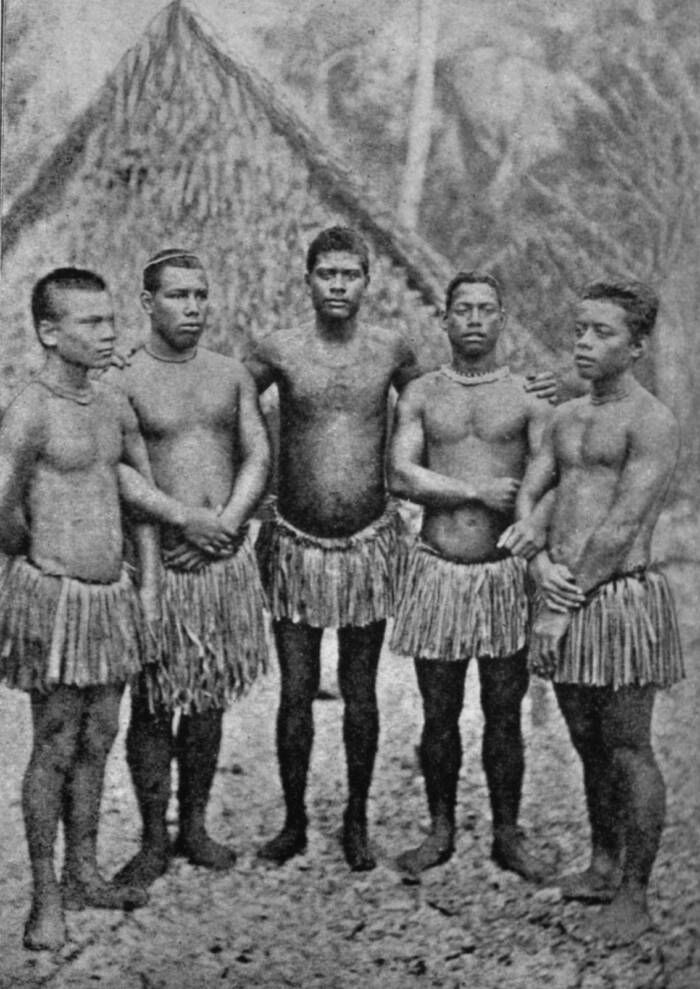

Public DomainA group of young, Indigenous Nauruan people. Circa 1914.

Though the island was first documented by British sea captain John Fearn, who sailed by Nauru in 1798 on his ship Snow Hunter, Europeans didn’t make extensive contact with the islanders until decades later. By 1830, European whaling ships and other trading vessels began to use Nauru as a supply stop. Europeans introduced guns and alcohol to the Indigenous Nauruans, which had dire consequences as the clans became increasingly competitive against each other, leading to an explosion of violence.

According to the CIA, violence on the island eventually escalated to a civil war in 1878. By the time the conflict ended, hundreds of Nauruans had been killed, and the island’s population shrunk from roughly 1,400 to around 900.

The conflict ended in 1888, when Germany forcibly annexed the island. The Germans banned alcohol, confiscated the islanders’ weapons, and brought in Christian missionaries to convert the Indigenous population. Soon afterward, phosphate was discovered on Nauru, and intensive phosphate mining became a major part of Nauru’s economy starting in the 1900s.

From that point on, Nauru was irrevocably — and often tragically — linked to the rest of the world. During World War I, Australian forces captured the island. During World War II, Nauru was occupied by Japan, who ordered some 1,200 Nauruans into forced labor. Because of its Japanese-controlled airstrip, the island was also bombed by American pilots during the conflict.

Public DomainA U.S. warplane that bombed Nauru’s airstrip. The island was occupied by the Japanese during World War II.

When the war ended, Nauru became a United Nations trust territory. Though there was some discussion of relocating all Nauruans to Curtis Island, which is part of Queensland, Australia, the people of Nauru rejected this idea. Instead, the island became an independent republic in 1968.

But living on Nauru has its difficulties.

Challenges Of Living On Nauru Today

NAURU JULY 2007/Wikimedia CommonsA group of Nauruans participating in a walk to support general fitness and to fight diabetes. Nauru has extremely high rates of obesity and Type 2 diabetes, and low life expectancies in general.

Today, Nauru faces a number of unique challenges.

One comes from its long history of aggressive phosphate mining. Though the phosphate industry once employed many people on the island — and briefly made Nauru one of the wealthiest countries in the world — it also left a devastating ecological impact that’s deeply felt to this day.

Not only did phosphate mining hollow out the center of the island, making about 80 percent of the land into an uninhabitable wasteland, but it also left a layer of toxic dust on the country. Contaminants like cadmium residue and phosphate dust have also polluted the island’s surrounding water and air.

What’s more, phosphate resources on Nauru have largely dried up. Mining more or less ended on the island in 2006 — though some have been making an effort in recent years to painstakingly mine the remaining phosphate. That means that the island’s main source of income has also been depleted in the 21st century, leading to high unemployment rates.

Nauruans have sought other forms of wealth, including hosting a controversial refugee detention facility for Australia in the 2000s and 2010s. Conditions there were so horrific, one woman said, “It is like a slow death for me. I don’t want to come to Australia any longer. My only desire is death.”

Though Nauru once had a valuable mining trust, a series of incompetent and corrupt government decisions squandered away much of the country’s wealth, including an unwise investment in a West End musical about Leonardo da Vinci and numerous failed hotels. In recent years, the government has turned to selling passports in the hopes of raising money to protect its people from rising seas amidst the ongoing climate crisis.

Lorrie Graham/AusAID/Wikimedia CommonsA phosphate mining site on Nauru. The island’s once-lush landscape is now full of jagged rocks.

Meanwhile, life on Nauru is also challenging because of the island’s relative isolation. Nauru has no rivers or streams, and most of its drinkable water has to be imported. Because of its lack of agriculture, most of Nauru’s food products — and other basic goods — are imported as well.

This has caused other problems for Nauru — namely, high rates of diabetes and obesity. It’s been estimated that as many as 97 percent of men and 93 percent of women on the island are obese or overweight. According to reporting from NPR in 2015, islanders mostly eat a diet of white rice, instant noodles, soda, and tinned food. Fast food is also popular across the nation.

Binge drinking and tobacco use are also rampant, and widespread alcoholism has led to numerous incidents of drunk driving and domestic violence. There have been vigorous public health efforts on the island, but islanders continue to struggle with unhealthy alcohol use, smoking, diabetes, and obesity — and the many negative effects — today.

As such, though Nauru is a unique republic with a fascinating history, it can also be a hard place to live. Isolated, environmentally ravaged, and largely dependent on imports, it has its fair share of challenges. And in the era of climate change and rising sea levels, Nauru’s future is anything but assured.

After reading about Nauru, the troubled island nation that’s the third-smallest country in the world, discover the story of North Sentinel Island, home to “the most isolated people in the world.” Or, go inside the mystery of why the famous Easter Island statues were built.