In 1942, the U.S. Marine Corps recruited 29 Navajo speakers to create an unbreakable code to use in the Pacific Theater — and by the end of the war, more than 450 Navajo Code Talkers had helped the Allies to victory.

During World War II, the Allied powers needed a way to transmit secret messages that enemy troops couldn’t decipher. So, in 1942, the U.S. Marine Corps recruited a group of men who would become known as the Navajo Code Talkers to make that happen.

The original 29 recruits were tasked with creating an unbreakable code using their native tongue. The Navajo language is incredibly complex and had no alphabet until the mid-20th century. It was essentially incomprehensible to anyone outside of the small pocket of southwestern American Indigenous people who spoke it — and that made it the perfect candidate for a wartime code.

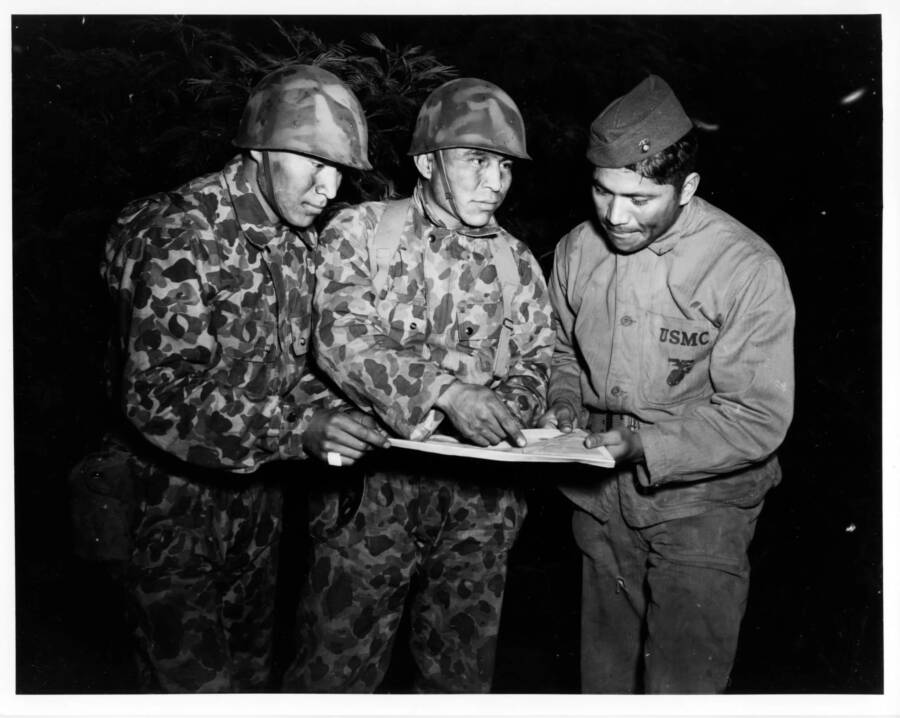

National ArchivesCorporal Henry Bake Jr. and Private First Class George H. Kirk, Navajo Code Talkers serving with a Marine Corps signal unit, operate a portable radio set in a clearing that they have hacked in the dense jungle behind the front lines in December 1943.

For the final three years of the war, hundreds of Navajo speakers served in the Pacific Theater, encoding, transmitting, and translating messages about Japanese troop movement, artillery locations, battle plans, and more. They played a key part in the Allies’ victory — but their efforts went unrecognized for decades.

It wasn’t until 1968 that the Navajo Code Talkers’ vital role in World War II was revealed, and they weren’t officially honored until 2000. This is the little-known story of the Indigenous Marines who helped the Allies win the war.

The Creation Of The Navajo Code

In 1942, the Allies were pressed in both theaters of World War II. The Nazis had occupied France, and England was still struggling to cope with the effects of the Blitz. Communication between Allied soldiers was becoming difficult as Japanese troops were getting better at breaking their codes.

It seemed that almost every form of communication had a flaw. Then, a man named Philip Johnston put forth an idea that would change everything.

Johnston was a civil engineer from Los Angeles who had read about the issues that the United States was having with military security. The son of missionaries, Johnston had grown up on a Navajo reservation, where he became fluent in the Indigenous language. He knew it was exactly what the government needed.

When Johnston presented his idea to Marine officers, they were initially skeptical. However, they agreed to give his plan a try, and they recruited 29 Navajo men to develop the secret code.

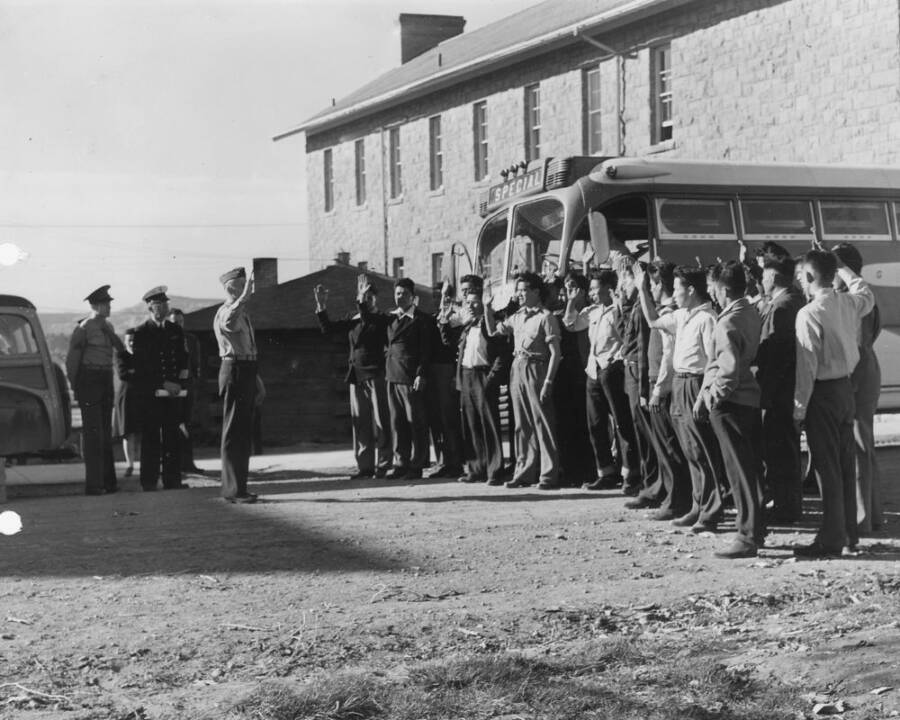

National Archives/Wikimedia CommonsThe first 29 Navajo Code Talker recruits being sworn into the U.S. Marine Corps at Fort Wingate in New Mexico.

The men took words from the Navajo language and applied them to military terminology. According to the National Museum of the American Indian, Corporal William McCabe, one of the original recruits, explained, “All the services, like the army, and divisions and companies, and battalions, regiments… we just gave them clan names. Airplanes, we named after birds… the buzzard is a bomber, and the hawk is a dive bomber, and the patrol plane is a crow, and the hummingbird is the fighter.”

The new Marines also created an alphabet in which the first letter of a Navajo word corresponded with an English letter. For instance, the term for ant — wo-la-chee — represented the letter “A.” The initial code consisted of 211 vocabulary terms in addition to this alphabet. Once the cipher was created, it was time to put it to the test.

The Navajo Code Talkers Head To War

Unlike conventional military codes, which were long and complicated and had to be written out and transmitted to someone who would then have to spend hours decoding them on electronic equipment, the Navajo code’s brilliance lay in its simplicity. The code relied solely on the sender’s mouth and the receiver’s ears and took much less time to decipher. During the initial test run, the Code Talkers translated, sent, and deciphered a message in less than three minutes.

Furthermore, the code had another advantage: Because the Navajo vocabulary words and their English counterparts had been picked at random, even someone who managed to learn Navajo couldn’t break the code, as they would only see a list of seemingly meaningless Navajo words.

The Marine Corps leadership was impressed, and they immediately began implementing the code in the Pacific Theater.

National ArchivesFrom left to right: Private First Class Peter Nahaidinae, Private First Class Joseph P. Gatewood, and Corporal Lloyd Oliver, Navajo Code Talkers with the 1st Marine Division in the Southwest Pacific.

The code was so effective that what started as a group of 29 men ballooned to more than 450 by 1945. While the cipher was invaluable in many aspects of war, the Navajo Code Talkers got their shining moment during the Battle of Iwo Jima. For two days straight, six Navajo Code Talkers worked around the clock, sending and receiving over 800 messages — without making a single translation error.

Major Howard Connor, the signal officer in charge of the mission, praised the efforts of the Code Talkers, according to the CIA, saying, “Were it not for the Navajos, the Marines would never have taken Iwo Jima.”

Navajo Code Talkers were used through the end of the war — and their cipher remained unbroken. But the vital part they played in the conflict wouldn’t be recognized until decades later.

The Legacy Of The Navajo Code Talkers

After World War II ended, the Navajo Code Talkers were forbidden to talk about their role in case the military needed to use their language again in the future. The Marines weren’t even allowed to tell their family members that they had helped the Allied powers win the war.

U.S. Marine Corps/Public DomainA Navajo Code Talker veteran in 2012.

It wasn’t until 1968 — more than 20 years after the war came to an end — that the operation was declassified and the Navajo Code Talkers could speak openly about their work. But it would take much longer than that for them to receive official recognition.

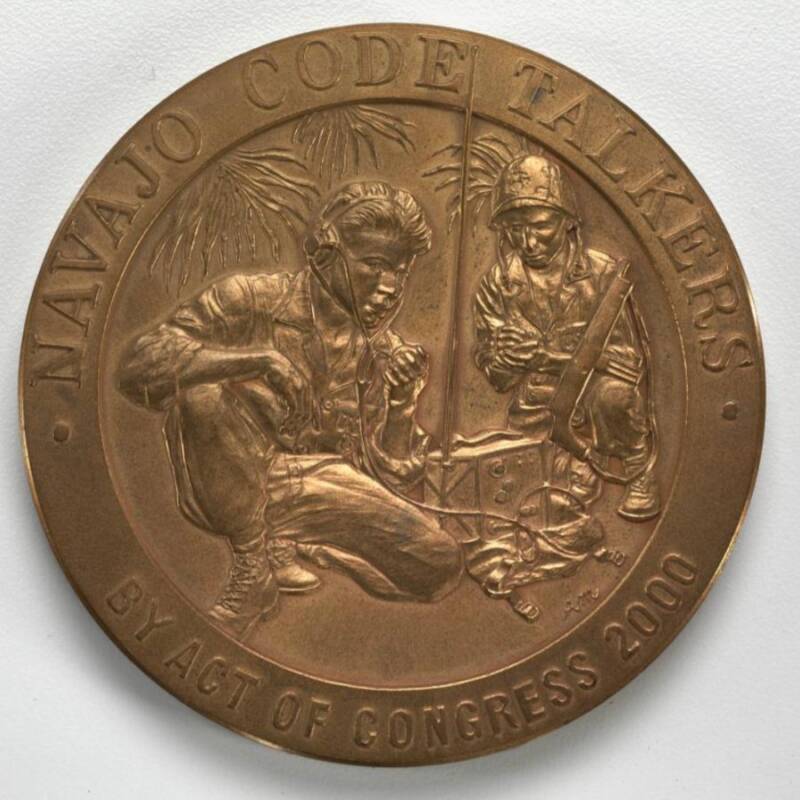

In 1982, President Ronald Reagan announced that Aug. 14 would be “Navajo Code Talkers Day.” And in 2000, President Bill Clinton awarded the Congressional Gold Medal to the original 29 Code Talkers. However, by the time President George W. Bush presented the medals in 2001, just four of the initial recruits were still alive.

National Museum of the American IndianThe Congressional Gold Medal honoring the Navajo Code Talkers.

Still, the Navajo Code Talkers are remembered today for their loyal service to a country that had spent decades trying to suppress their identity.

Many of the Navajo Marines were recruited from schools that aimed to Americanize the Indigenous group and encouraged them not to use their native language. But in the end, it was this very language that helped the Allied powers to victory.

After learning about the Navajo Code Talkers and their service in World War II, check out these heart-stopping photos from World War II. Then, read about Calvin Graham, World War II’s youngest decorated soldier.