A study analyzing fish-heavy fatty acids discovered in pottery shards has shed new light on our understanding of the southeastern European diet in the Neolithic Age.

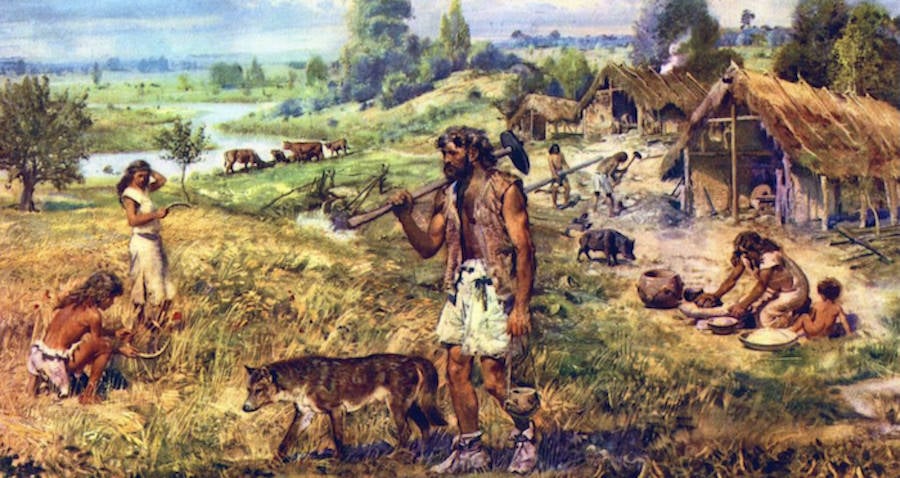

Libcom.Org/Out of The Woods

Researchers at the University of Bristol have garnered new insight about the dietary habits of Neolithic people living near the Danube River in southeastern Europe 8,000 years ago.

The study, published in the Proceedings Of The Royal Society B, analyzed more than 200 8,000-year-old pottery shards to reveal that what was once believed to be a primarily meat and dairy-based period actually included far higher fish consumption than previously thought.

This discovery has shed new light on this subset of Neolithic people living in the Iron Gates region of the Danube — an area between modern-day Romania and Serbia that marks the first appearance of Neolithic culture — and what they actually ate.

RGB Stock Images/DYETA fish fossil from the Neolithic Age.

It was previously believed that the Neolithic period — which began 12,000 years ago and marked the end of the Stone Age — turned its back on the fish-heavy diet of the Mesolithic age, as farming had established itself as a reliable alternative and gave way to a new diet of meat and dairy products.

The new findings (made via a sophisticated technological process known as chromatography-mass spectrometry, which indicates what kind of organic substances the discovered fatty acids originate from) are thus crucial in terms of understanding the practical details of our evolution as a species in this particular area and time.

“The findings revealed that the majority of Neolithic pots analysed here were being used for processing fish or other aquatic resources,” explained Dr. Lucy Cramp, lead researcher of the study and professor of the university’s Department of Anthropology and Archaeology. “This is a significant contrast with an earlier study showing the same type of pottery in the surrounding region was being used for cattle, sheep for goat meat and dairy products.”

“It is also completely different to nearly all other assemblages of Neolithic farmer-type pottery previously analyzed from across Europe (nearly 1,000 residues) which also show predominantly terrestrial-based resources being prepared in cooking pots (cattle/sheep/goat, possibly also deer), even from locations near major rivers or the coast.”

Wikimedia CommonsThe Danube River

While we, ourselves, continue to eat fish on a regular basis even with the long-established advent of farming and domestication of animals, it’s highly unusual for the Neolithic people to have continued their aquatic diet in wake of the overwhelming benefits of a reliable, secure source of food production. Dr. Cram and her fellow researchers aren’t entirely sure why this particular subset of Neolithic people did, but they do have some theories.

The vast sturgeon population going down the Danube River, for instance, would’ve been a strong potential incentive to continue the fishing habits of earlier periods.

The study also considers this dietary anomaly a potential result of cultural blending between overlapping Late Mesolithic and Early Neolithic populations who populated the Danube region during this transitionary period.

The fish-based residue found in these pots may well point toward a change in how fish was prepared, with this new technological advent allowing people to make stews, soups, or oil. However, the exact reason is yet unknown — and may remain so forever.

After learning more about the Neolithic diet, read about archaeologists finding the world’s oldest cheese in an ancient Egyptian tomb. Then, read about a 25,000-year-old mammoth rib that was pierced by arrows from early human hunters.