Ann Atwater was a single mother in Durham, North Carolina when she helped integrate the city's schools with C.P. Ellis in 1971 — a story that inspired the film "The Best Of Enemies."

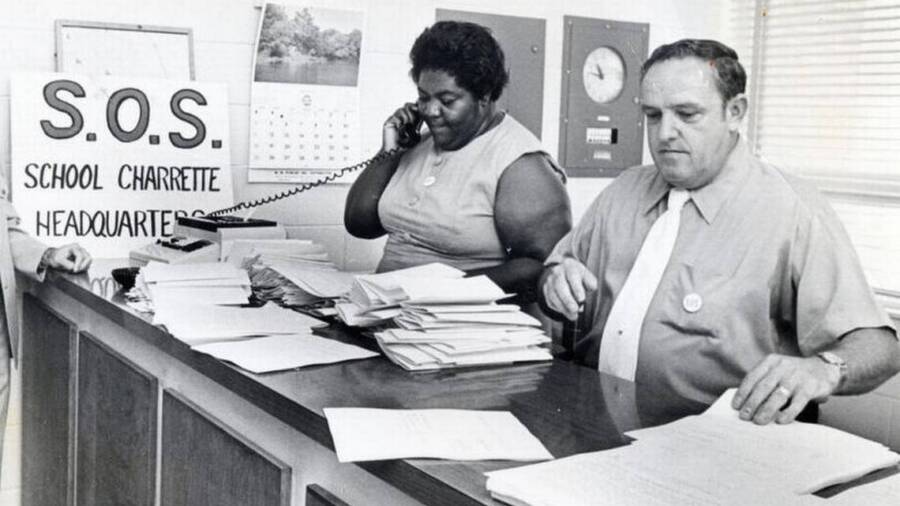

Jim Thornton/The Herald Sun Collections/University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill LibrariesAnn Atwater and C.P. Ellis were named co-chairs of the Durham, North Carolina’s charrette S.O.S., “Save Our Schools.”

She was a poor black woman raising children alone in the South in the mid-20th century. Ann Atwater found her voice as a community activist to stand up to slumlords and bigots — and yet, one of the most transformative relationships in her life was with a Klansman.

This is the story of Ann Atwater, political activist and desegregationist, the true story behind the 2019 film The Best of Enemies.

Ann Atwater’s Early Life

Ann Atwater’s life didn’t start off easy. Born to sharecroppers on July 1, 1935, in Hillsboro, North Carolina, her meager beginnings were compounded when she found herself pregnant at age 14. She married the baby’s father, French Wilson, but their baby died soon after birth. Two years later, they had a daughter named Lydia.

In the early 1950s, Atwater and her daughter moved to Durham to join Wilson.

“My husband was already here, and he sent back for me and my oldest child, and he told me he had a place for us to live,” Atwater later recalled.

This wasn’t actually true — there was no house waiting for her when she arrived in Durham. Instead, they spent the first bit of their married life sharing a single room with another man, with him in one bed while Atwater and Wilson shared the other with their baby.

The marriage was unhappy, and when Wilson got a job in Richmond, Virginia and asked Atwater to uproot herself again, she countered:

“I already followed you to Durham. I’m not following you any further.”

At this point, the couple had another daughter, Marilyn. The couple divorced, and Atwater supported herself and her two children as a maid for 30 cents an hour before turning to Social Services for help.

From Abject Poverty To Housing Advocate

Ann Atwater was used to struggling, but she hit some truly hard times. Welfare was only providing $57 a month, and she was leasing a dilapidated house where she was $100 behind her rent. For food, she and her daughters could only afford rice, cabbage, and gravy while she made her daughters clothes out of the bags the rice came in.

“We didn’t have to worry about any air, because the cracks were all along the house,” Atwater later recalled, “you could just stand on the outside and look on the inside, you didn’t have to go to the window. And the house was so poorly wired that when the man cut off my lights for nonpayment of [the] light bill, I could stomp on the floor and the lights would come on and I’d stomp on the floor and they’d go off.”

It was at this house in Durham’s Hayti District where she met Howard Fuller, the man that would help her reach her destiny as a pioneering advocate.

Fuller looked at the house and asked Atwater if she’d like help in fixing it. She had little faith that he’d be able to get her landlord to do anything, but she agreed to go with him to a meeting for his organization.

Fuller was bankrolled by the North Caroline Fund to do some community organizing and soon drafted Atwater into the group. He convinced her landlord to fix her house, helped pay back her debt, and helped her find her path.

Operation Breakthrough And The 1971 Charrette

That path involved a 17-week training course, where Ann Atwater learned the ropes of community organizing and the ins and outs of tenant rights along with the city’s housing code.

Through Fuller, Ann Atwater was introduced to Operation Breakthrough. Breakthrough was a project designed to alleviate poverty by teaching residents how to address its root causes, and by organizing the community to create a social security net. They showed community members how to cultivate gardens or how to chip in and fundraise together to improve their neighborhoods.

www.schoolforconversion.orgAnn Atwater organizes neighbors after completing Community Action Training with the North Carolina Fund.

Atwater found her niche. She grew to love fostering communities, teaching them how to take care of themselves, and not put up with the injustices they faced in their daily lives.

Through Operation Breakthrough, Atwater was selected for the 1971 charrette — or series of planning meetings — over the integration of Durham’s schools.

Bill Riddick, a professor and consultant, was contracted by union organizers to help solve the crisis. He organized a federally-funded sit-down which would rule on the issue one way or another, held for 10 days from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m.

Atwater was chosen as one of the charrette’s leaders. The other was C.P. Ellis.

Ann Atwater And C.P. Ellis

The pair had met years before.

“We were at a meeting downtown together,” said Ann Atwater years later, “and he kept yelling ‘nigger’ this and ‘nigger’ that. I pulled out the knife that I kept in my handbag and opened the blade. As soon as he got close to me, I was going to grab his head from behind and cut him from ear to ear. But my pastor was sitting there and saw me holding the knife. He grabbed my hand and said, ‘Don’t give them the satisfaction.'”

C.P. Ellis was the Grand Cyclops of the Durham chapter of the Ku Klux Klan, raised in a poor white family that taught him to hate black people.

“I didn’t like them. I didn’t like integration. I didn’t like the demonstrations downtown,” recalled Ellis some 30 years after the charrette. “I didn’t like Ann boycotting stores. And she was an effective boycotter, too. She was making progress. I hated her guts.”

The enmity was mutual, and the charrette seemed stuck. But both Ann Atwater and C.P. Ellis had epiphanies.

For Ellis, “it finally came to me… that I had more in common with poor black people than I did with rich white ones.”

Atwater pointed to another moment:

“When the children got us together and said they wanted to go to school together. We looked at each other. Like fools we’d been arguing about the wrong things and hadn’t been doing anything to make the school system better.”

They decided to integrate the schools. In front of a crowd, C.P. Ellis stood up and ripped apart his Klan membership card.

Truth And Fiction In The Best Of Enemies

Courtesy of STXfilmsAnn Atwater in an image from the 2002 documentary An Unlikely Friendship.

Like all historical fiction, the 2019 film The Best of Enemies takes a bit of license with reality. For instance, the film never mentions Ellis’ KKK-inspired hatred of Catholics.

But much rang true. Ann Atwater was a pioneer of community organizing and black advocacy. C.P. Ellis did rip up his KKK card, swearing “I never did go back to the Klan after I left that school program.”

Ann Atwater and C.P. Ellis remained close until his death in 2005, and Ellis’ family asked Atwater to give the eulogy. She even experienced racism in that moment, when a funeral home worker doubted she knew the deceased.

VarietyThe Best of Enemies depicts the unexpected friendship between Ann Atwater and C.P. Ellis, who’s played by Sam Rockwell.

Atwater replied: “He was my brother.”

The unlikely friendship is remarkable, but most of all, Ann Atwater’s legacy is that of a fierce defender of integration to whom the word “no” meant nothing.

For more vivid tales of 20th-century race relations like the true story of “The Best Of Enemies” of Ann Atwater and C.P. Ellis, read about Malcolm X’s brutal assassination and America’s struggle for civil rights.