The Rise Of The Chinatown Gangs

The first resident of Chinatown was Ah Ken, a cigar salesman who arrived in New York in 1858. Many believe he was able to afford his shop by renting out rooms to Chinese immigrants, effectively building Chinatown around his own home in the process.

Unlike earlier European immigrants who had had religious, cultural, or linguistic commonalities to help them adjust to New York, the average Chinese immigrant was faced with considerably more difficulty.

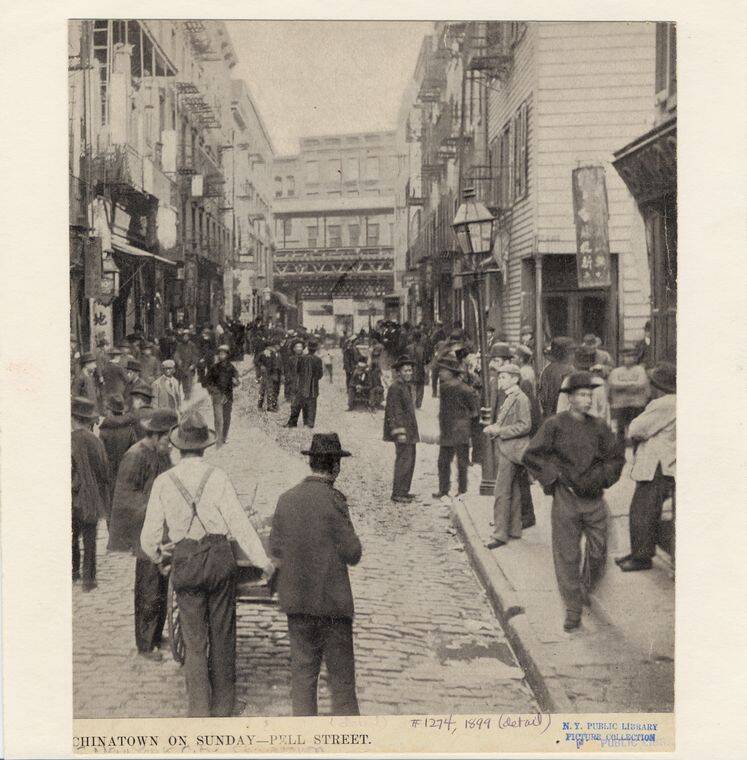

New York Public LibraryA view down Pell Street in Chinatown in 1899.

For one thing, New Yorkers wanted little to do with Chinese immigrants apart from the occasional trip to their alleged opium dens. Under the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, many of these immigrants were limited from even entering the United States at all.

The act also made the present Chinese immigrants in the country alien residents. To make matters worse, many Chinese women were unable to join their husbands who were already in the country when the law was passed.

What were these isolated, desperate individuals surrounded by hostility and discrimination to do? Deprived of their legal rights, some Chinese immigrants turned to the criminal underbelly in response.

Secret societies were established to organize crime in Chinatown. These were called tongs, originally known as mutual aid associations.

When exactly their connection to crime started is unclear. But by the time the On Leong Tong was established in 1893, tong rule had clearly seeped into New York. And things were about to get bloody.

The Terror Of The Tong Wars

The full story of the tongs and the consequent Tong Wars spans from San Francisco to New York. Aside from its vast territory, the scale of violence in the Tong Wars was almost on a par with the Italian Mafia of the 1930s.

The cause of this war was what one might expect out of a clash of gangs: There was a struggle between two Chinese tongs for control of Chinatown.

Library Of CongressTong members arrested after a battle. 1906.

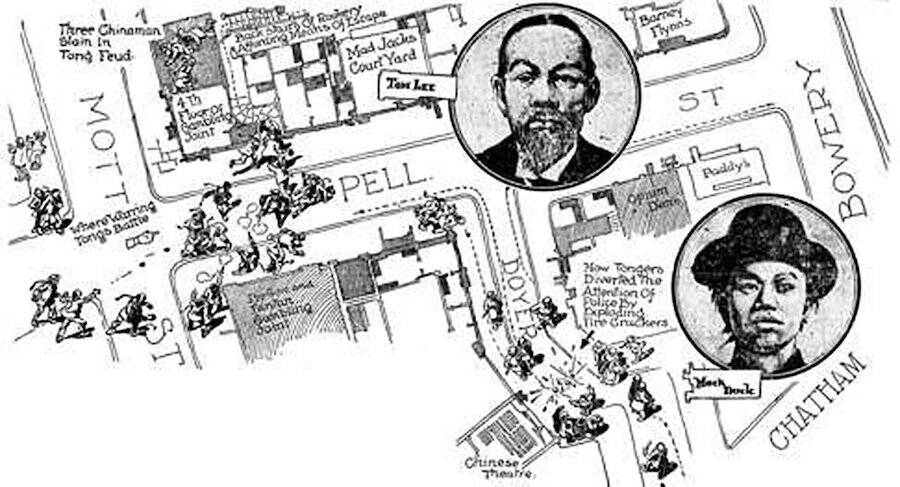

Tom Lee was an established behind-the-scenes operator of the New York-based On Leong Tong. Lee’s tong soon garnered a dominant reputation even outside Chinatown and had strong ties to Tammany Hall.

But in the late 1890s, a rival appeared in the Hip Sing Tong. Leader Sai Wing Mock, a.k.a. Mock Duck, soon began to push into Lee’s territory.

On Aug. 12, 1900, a laundryman and member of the Hip Sing Tong named Lung Kin visited 9 Pell Street in Chinatown. At 6 p.m., he stumbled into a hallway as gunshots rang out — aiming straight at him.

An unknown number of tong members scattered from the room and from the building, leaving Lung to collapse in a pool of his own blood. Later that night, police arrested Gong Wing Chung, a member of the On Leong Tong.

The New York Times reported at the time: “When confronted with the charge of murder, [Gong Wing Chung] never moved a muscle. As he was being led away, a smile played over his face.”

Just six weeks later, Ah Fee, an associate and alibi witness of Chung’s, was murdered in retaliation.

Public DomainMap of the Tong War feud. 1906.

Lee was known to derive power from money, respect, and relationships, whereas Mock was more comfortable resorting to violence and brutality.

Within weeks of demanding half of the On Leong Tongs’ gambling operations, Mock’s men allegedly set fire to one of the group’s boarding houses. Not long after that, an On Leong “hatchet man” slew a Hip Sing he met in the street.

When Hip Sing member Sue Sing was brought to trial for the murder of Ah Fee, prosecutors saw an opportunity to use his trial as a means of reforming Chinatown. Authorities thus charged leaders of the Hip Sing Tong as well, including Mock Duck, who was suspected of planning the assassination.

Sing was convicted and sentenced to prison for life, while a deadlocked jury saved Mock Duck from going to jail. Shaken nonetheless, Mock left town for a time before making another play for control of Chinatown.

Mock’s return marked another moment in the evolutions within the tongs. Originally armed with meat cleavers in the late 1800s, the tongs began to use revolvers and other firearms around 1900. Explosives, used more rarely, entered into their operations around 1912.

Mock incorporated a chainmail vest beneath his clothes, a decision that ultimately saved him during several assassination attempts.

Mock was convicted only once for a minor crime in 1912 and spent just two years in prison before keeping a low profile until the end of his life in 1941. Unlike many other gang members, he died of natural causes.

Public DomainWeapons seized from tong members during a Chinatown police raid in 1922.

One of the most famous remnants of New York’s Tong Wars is a still-surviving nickname for Doyers Street.

Doyers Street feels more like an alley than a full-fledged road. It’s one block long and cut in half by a nearly 90-degree turn. This so-called “Bloody Angle” proved ideal for ambushing enemies.

Today, Doyers Street is most famously home to Nom Wah Tea Parlor, the oldest dim sum restaurant in New York. Nom Wah will celebrate its 100th anniversary in 2020.

By the time Nom Wah opened, Chinatown was mostly free of the brothels and opium dens for which it was once known.

Momentum within the Chinatown tongs slowed in the early 1900s when police raids proved to be the most effective in the city’s history.

Many of their operations were closed down by city authorities, and so the warring tongs came to a truce in 1906. The wars would kick off at few more times, however, surprisingly ending with Mock’s quiet retirement to Brooklyn.