Before his death in 1582, Oda Nobunaga conquered much of central Japan and laid the groundwork for the unification of the country, making him the first of three "Great Unifiers" in Japanese history.

Public DomainOda Nobunaga, the samurai who brought an end to Japan’s fighting factions.

In the 16th century, Japan was a country consumed by chaos. During the so-called Sengoku Period, the traditional feudal structure that united the country had shattered, resulting in constant warfare.

Powerful lords and their samurai followers fought against each other for dominance. At the same time, the traditionally closed society was struggling to adapt to new ideas and technologies introduced by Europeans.

Into that chaos stepped Oda Nobunaga. Brilliant, bold, and brutal when he needed to be, Nobunaga began the long process of reunifying Japan. He would succeed — but it would also cost him his own life.

This is the story of Oda Nobunaga, the “Great Unifier” of Japan.

How The ‘Fool Of Owari’ United His Clan

Oda Nobunaga, born on June 23, 1534, in Nagoya, Owari Province, was the heir of Oda Nobuhide, a minor daimyō and head of the Oda clan.

Public DomainA wooden statue of Oda Nobuhide, Oda Nobunaga’s father, at Banshō-ji, Nagoya.

As a youth, Nobunaga was known for his unconventional and often erratic behavior. He was difficult to control and often displayed a penchant for mischief, mingling with commoners, and generally showing little regard for his social status. As the Sengoku Chronicles reports, these behaviors earned him the nickname “Fool of Owari.” However, Nobunaga was not completely foolish. He also developed an interest in firearms, something that would later help him consolidate power as he marched across Japan.

In 1549, Nobunaga’s father made peace with the daimyō of the neighboring Mino Province and, to solidify this peace, married Nobunaga to the daimyō’s daughter Nōhime. But while their marriage may have strengthened the ties between two clans, things within Nobunaga’s Oda clan were fractious.

In 1551, Nobunaga’s father died. Though Nobunaga was his father’s legal heir, he found it difficult to rally his family behind him because of his youthful exploits. His eccentric behavior during his father’s funeral — Nobunaga reportedly threw ceremonial incense at the altar — didn’t help his case.

Public DomainA portrait of Oda Nobunaga.

But Nobunaga met his family’s doubts about him with military force. He raised an army of 1,000 and proceeded to crush everyone who opposed him, including his uncle Oda Nobutomo and his brother Oda Nobuyuki. In 1554, Nobunaga defeated his uncle at the Battle of Kiyosu Castle and forced him to die by ritual suicide, or seppuku. In 1557, Nobunaga also had his brother killed after learning that Nobuyuki was conspiring against him.

By 1559, no one else opposed Oda Nobunaga’s control over Owari Province. Unsatisfied with peace within his own borders, Nobunaga next turned his attention outward, starting with the rival Imagawa clan.

Oda Nobunaga Leads His Clan To Victory And Establishes Himself As A Military Visionary

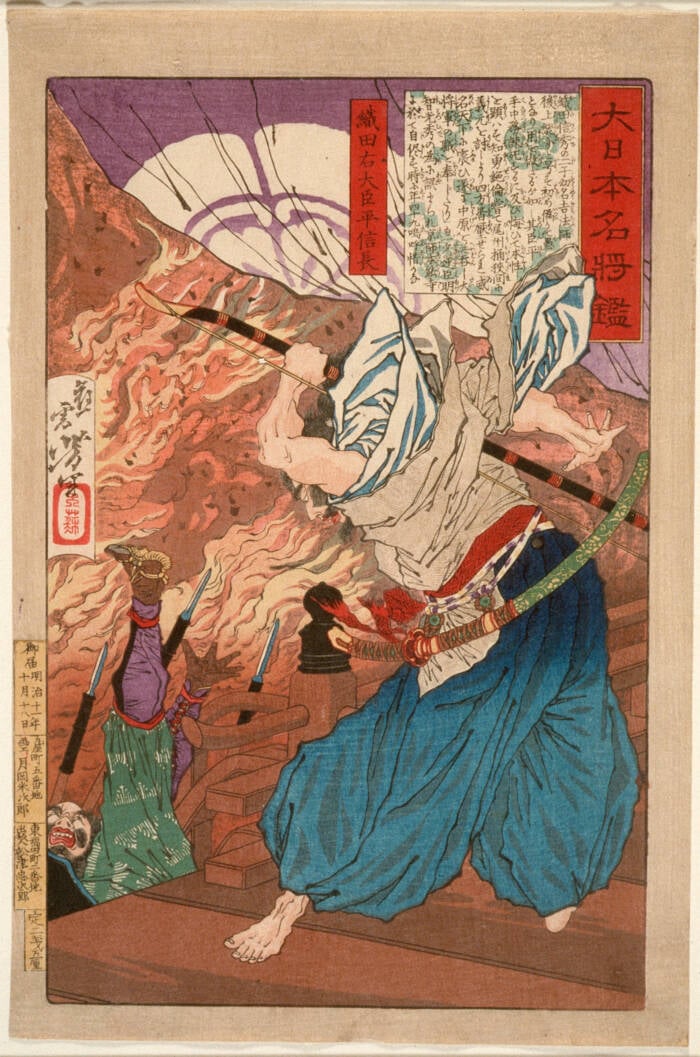

Public DomainAn ukiyo-e print of Nobunaga fighting.

The leader of the Imagawa, Imagawa Yoshimoto, was one of the most powerful feudal lords in Japan. And in 1560, he decided the time had finally come to make a play to become shōgun, the overlord of the country. But Oda Nobunaga wasn’t going to sit by and watch it happen.

When Yoshimoto raised a force of 25,000 men to attack the capital city of Kyoto, Nobunaga rallied his own soldiers to challenge Yoshimoto’s forces. There was just one problem: Nobunaga could only come up with a couple of thousand men. But Nobunaga’s brilliance made up for his lack of soldiers.

First, he filled out his ranks with dummy samurai stuffed with straw. Next, Nobunaga waited until Yoshimoto’s troops let their guard down and began drinking sake after celebrating a victory. Then, in the wake of a rolling thunderstorm, Oda Nobunaga led his small army on an audacious raid straight into Yoshimoto’s camp.

Public DomainA 1882 depiction of the Battle Of Okehazama, in which Oda Nobunaga triumphed over Imagawa Yoshimoto despite having far fewer men.

The so-called Battle of Okehazama was a rout. Yoshimoto’s superior army was defeated, and Yoshimoto was killed. In the aftermath, Oda Nobunaga emerged as one of Japan’s most feared military leaders.

How Oda Nobunaga’s Visionary Tactics Helped Unify Japan

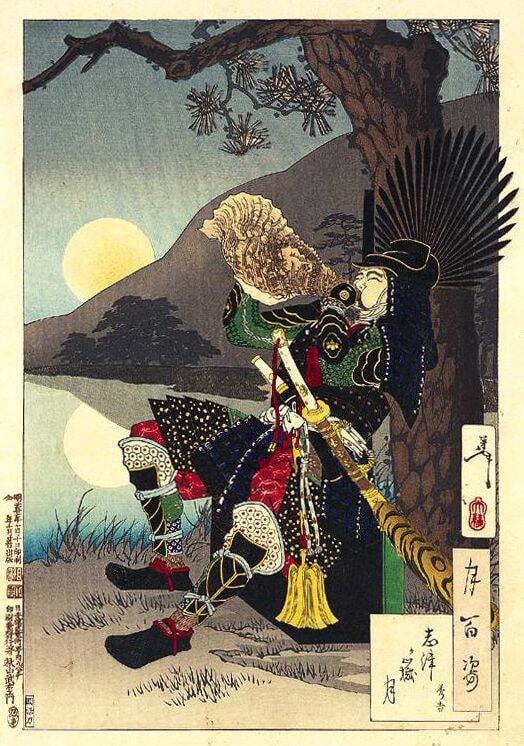

Public DomainUkiyo-e print of Oda Nobunaga by Kuniyoshi Utagawa.

Over the next two decades, Oda Nobunaga solidified his control over the country by crushing anyone who opposed him.

Part of Nobunaga’s success came from his use of firearms. The Portuguese had brought guns to Japan in 1543, and, as Tokyo Weekender reports, Nobunaga was among the first to use the weapons during war. In 1549, when he was still a teenager, he even outfitted 500 soldiers with matchlock muskets. Decades later, in 1581, Nobunaga also allegedly developed an effective strategy in which he had his men fire in alternating rows.

In addition, Nobunaga broke with tradition by choosing men to lead his army based on ability, not their social status. One of his greatest generals — and eventual successor — Toyotomi Hideyoshi, started as a lowly peasant soldier. But after demonstrating his skill as a warrior at the The Battle of Okehazama, Nobunaga eventually promoted him to become his top lieutenant.

Public DomainToyotomi Hideyoshi rose from being a peasant to Oda Nobunaga’s successor, dubbed the second “Great Unifier” of Japan.

As Nobunaga’s military campaigns continued to yield success after success, he also began to implement significant economic reforms in his conquered territories. Nobunaga abolished monopolies and opened up free markets, fostering commerce and weakening the economic power of rival daimyōs and militant Buddhist sects. He minted the first Japanese currency in hundreds of years, and reorganized the tax structure. Moves like these lay the groundwork for a more unified Japanese economy.

Come 1568, Nobunaga entered Kyoto and installed Ashikaga Yoshiaki as a puppet shōgun, effectively putting Nobunaga himself in control of the shōgunate. However, Nobunaga deposed Yoshiaki five years lager in 1573. This marked the end of Ashikaga shōgunate and, by 1579, Oda Nobunaga controlled almost all of central Japan.

His campaigns against rival daimyōs continued throughout the 1570s and 1580s, and Nobunaga earned a reputation for ruthlessness. But while Nobunaga brought about sweeping change in Japan, there were those who disagreed with his vision for the future — and plotted his downfall.

The Honnō-ji Incident And Oda Nobunaga’s Death By Seppuku

Wikimedia CommonsA statue of Oda Nobunaga.

By 1582, Oda Nobunaga was firmly in control central Japan. His territory extended over 20 provinces, and he was preparing to expand his empire to the west. Nobunaga was more powerful than he had ever been before. But his days were numbered.

In June of that year, Nobunaga sent reinforcements to his loyal aide Toyotomi Hideyoshi, which include the general Akechi Mitsuhide. Nobunaga then went to the temple of Honnō-ji in Kyoto for a tea ceremony. But instead of going to help Hideyoshi, Mitsuhide — for reasons unknown, possibly out of personal animosity — brought his troops to Honnō-ji instead.

In some versions of Oda Nobunaga’s death, Mitsuhide set the temple on fire. In others, his men attacked. But both stories end in the same way. Trapped, and with no other option, Nobunaga committed ritual suicide.

Wikimedia CommonsOda Nobunaga’s grave at Honnō-ji Temple.

With Oda Nobunaga dead, Mitsuhide sought to become shōgun himself. But he met fierce opposition in the form of Toyotomi Hideyoshi, who rushed back to Kyoto upon hearing word of Mitsuhide’s treachery.

He quickly led his army toward Kyoto and smashed Mitsuhide’s army in the field. Mitsuhide was killed during the battle, and Hideyoshi stepped into the power vacuum as the top warlord of Japan.

Hideyoshi continued Nobunaga’s mission to unify the country, a task that was eventually completed by his own successor, Tokugawa Ieyasu. That’s why Oda Nobunaga, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, and Tokugawa Ieyasu are considered the three “Great Unifiers” of Japan.

As a popular Japanese saying goes, “Nobunaga pounds the national rice cake, Hideyoshi kneads it, and in the end, Ieyasu sits down and eats it.” Today, Oda Nobunaga is remembered as the first “great unifier” of Japan. Not a bad legacy for a man who people once called a fool.

Now that you’ve read about Oda Nobunaga, learn about the Onna-Bugeisha, Japan’s fierce female samurai. Next, discover the story Miyamoto Musashi, the Edo-era samurai famous for fighting with a double-bladed sword.