A fearsome samurai, Miyamoto Musashi was famous for his double-bladed swordsmanship, winning over 60 duels — and painting peaceful illustrations of birds.

Wikimedia CommonsMiyamoto Musashi was known for wielding two swords at once — in a technique that he invented.

Miyamoto Musashi was one of the greatest swordsmen in Japanese history, a figure whose status has truly become legendary throughout the centuries. His prowess in combat extended well beyond one-on-one duels, and in his later years, Musashi also established himself as a master painter, a talented writer, and a revered philosopher.

Even today, his teachings, as recorded in his 17th-century text The Book of Five Rings, serve as a guide for aspiring martial artists — and also people who are trying to succeed in business or find inner peace.

But who was this venerable figure, and why do his strategies still resonate nearly four centuries after his death?

Miyamoto Musashi’s Early Years

Miyamoto Musashi’s life has been well documented, though records of his early years remain murky. Most historians agree that he was likely born sometime in 1584, the son of martial artist Shinmen Munisai.

It is also clear that Musashi and his father did not get along, as he left his father’s home to live with his uncle, Dorinbo, at a young age.

Musashi showed early prowess with the sword, taking his first life at just 13 years old when he bested his first opponent, an older man, in single combat. And thus began Musashi’s life as a fearsome warrior.

In Musashi’s later teenage years, he became a soldier and fought on the losing side of the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600. This battle was a decisive conflict fought in Honshu between the vassals of Toyotomi Hideyoshi, a feudal lord and chief imperial minister who had died in 1598.

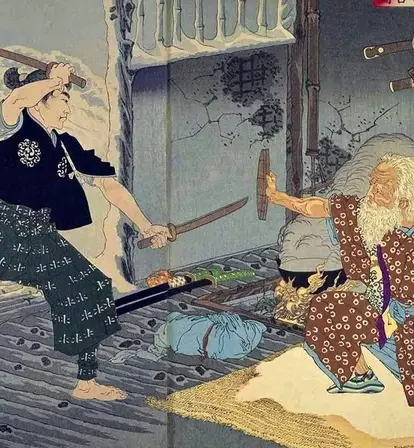

Wikimedia CommonsMiyamoto Musashi slicing a Tengu, a legendary creature from Japanese folklore.

On one side of the battle were Toyotomi loyalists who largely hailed from western Japan, led by daimyō Ishida Mitsunari. On the other side were supporters of Tokugawa Ieyasu, hailing from eastern Japan, who sought to usurp Toyotomi’s legacy and promote Ieyasu to a position of power. In the end, Ieyasu prevailed, laying the groundwork for the Tokugawa shogunate, which would ultimately rule over Japan until 1868.

Musashi, a Toyotomi loyalist, survived the battle. But since he was left with no master, he became what is known as a rōnin, or a masterless samurai, and set out to develop the perfect sword technique.

Becoming Japan’s Greatest Samurai

Eventually, Miyamoto Musashi created the technique nitō ichi-ryū, a style of fencing that involved using two swords at once. This technique is still widely admired today and is often referred to as kensai, which translates to “sword saint.” Unsurprisingly, it gave Musashi a huge advantage in combat.

Over the course of his life, Musashi claimed to have fought in more than 60 duels, according to the Niten Institute. Many of these swordfights were to the death — and he won every single one of them. His most famous duel, however, took place in 1612, and this fight helped establish Musashi as one of the most masterful swordsmen in Japan’s history.

The duel was against Musashi’s rival, a swordsman named Sasaki Kojirō.

The duel happened in 1612, when Musashi was about 28 years old. Kojirō and Musashi met on the small Japanese island of Funajima for the fight. Kojirō was known for his skills at wielding a nodachi, a long, traditional Japanese sword. Most of his opponents would likely prepare a similar weapon for the occasion. But Musashi faced Kojirō with a crude bokken, a wooden sword that he had fashioned from an oar on the way to the island.

SOURCENEXT/Alamy Stock PhotoA statue commemorating Miyamoto Musashi’s duel against Kojirō.

It was a surprisingly quick and decisive battle, with Musashi promptly incapacitating his opponent with a blow to the head.

The duel unquestionably helped cement Musashi’s legendary status as a samurai, but it also marked the end of an era. Believing that he had truly mastered the art of the sword and reached his peak, Musashi ultimately retired from dueling. That said, he didn’t put down the sword for good.

He would later take on students so he could pass on his techniques to younger samurai. And in 1637, he played a role in suppressing the Shimabara Rebellion, an uprising of Japanese Roman Catholics that ultimately failed, and put an early end to the Christian movement in Edo-era Japan.

Then, in his later years, Musashi contributed further to his legacy as a monochrome ink painter, philosopher, and writer. Many of his texts are still studied to this day. But his most iconic work would be his text on the arts of confrontation, strategy, and victory: The Book of Five Rings.

The Book Of Five Rings And Musashi’s Death

As the story goes, Miyamoto Musashi wrote his most legendary work during the final chapter of his life, when he was on his deathbed. He had spent the years following his duel with Kojirō traveling and teaching, but by the 1640s, he felt that his time on Earth would soon be coming to an end.

After suffering neuralgia attacks, he retired to a cave known as Reigandō in 1643. According to KCP International, he largely lived as a hermit in his final years as he completed the manuscript for The Book of Five Rings.

Wikimedia Commons“Shrike Perched in a Dead Tree,” a painting by Miyamoto Musashi.

Musashi finished the manuscript by 1645, ultimately passing it on to one of his devoted students who made sure it wouldn’t be forgotten.

Accounts of Musashi’s death vary, but he reportedly died either in Reigandō or somewhere near it in May or June 1645. His death was later described in the Hyoho senshi denki — “Anecdotes about the Deceased Master”:

“At the moment of his death, he had himself raised up. He had his belt tightened and his wakizashi put in it. He seated himself with one knee vertically raised, holding the sword with his left hand and a cane in his right hand. He died in this posture, at the age of sixty-two. The principal vassals of Lord Hosokawa and the other officers gathered, and they painstakingly carried out the ceremony. Then they set up a tomb on Mount Iwato on the order of the lord.”

But even though Musashi was no more, his legacy lived on for centuries.

Miyamoto Musashi’s Enduring Legacy

Miyamoto Musashi’s writings were eventually translated into several languages. Today, they often serve as a guide for businesses around the world. In fact, when The Book of Five Rings was first translated into English in the 1970s, American executives studied it closely, hoping to understand the mindset and management techniques of their Japanese colleagues.

But even though Musashi’s writings are largely applied to the business world in modern times, his teachings go well beyond that sphere and can be applied to many other situations in life. Take this quote from him, for example: “Think lightly of yourself and deeply of the world.”

Wikimedia CommonsMiyamoto Musashi on the banks of the Isagawa in Kawachi Province, meeting a man with a magnifying glass.

Beyond his legacy as a master swordsman and a brilliant philosopher, Musashi is also remembered today for the various paintings he created, particularly for his illustrations of birds, including Koboku meikakuzu (“Shrike Perched in a Dead Tree”) and Rozanzu (“Wild Geese Among Reeds”).

Countless novels, movies, and television shows have also been inspired by Musashi’s life — most recently Netflix’s anime series Onimusha.

Miyamoto Musashi certainly was one of Japan’s greatest warriors, but to refer to him solely as such is a discredit to the multifaceted man he was.

After learning about Miyamoto Musashi, learn about the rise and fall of the Japanese Empire. Or, read the story of Jules Brunet, the “last samurai” who resigned from the French military to fight for the shogunate.