From 1868 to 1945, the Empire of Japan reigned as a formidable world power — and perpetrated some of history's worst war crimes before and during World War II.

The phrase “Nazi Germany” inspires a horrific set of images in the minds of most Westerners. But when it comes to “Shōwa Japan” — the term used to designate the wartime Japanese Empire under Emperor Shōwa (or Hirohito) — the same phenomenon tends not to occur. And yet, Japanese war crimes during World War II were just as appalling as Nazi ones.

In the 1930s and 1940s, Japanese troops committed a number of atrocities across Asia. Some events are well documented, like the Rape of Nanking — also called the Nanjing Massacre — which left as many as 300,000 Chinese civilians dead. But there are also many lesser-known events, like the Bataan Death March, the Rape of Hong Kong, and the Manila Massacre.

So how did Japan get to that point? Like Germany and the United States, the country rapidly modernized in the late 19th century and set out to establish a sphere of influence. But Japanese society, which emphasized Japan as “the sacred motherland of all human races,” and sought to avoid subjugation by other nations, increasingly relied on a kind of cultural blitzkrieg.

These tactics made World War II-era Japan an unfathomably brutal place. By some estimates, there were upwards of 40 million deaths in the Pacific Theater — about half of whom were civilians killed by Japan’s military.

Below, delve into how and why Japanese war crimes came to be so widespread as the country’s power grew in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Then, see why they’ve been largely forgotten in the post-war era.

Inside The Origins Of The Japanese Empire

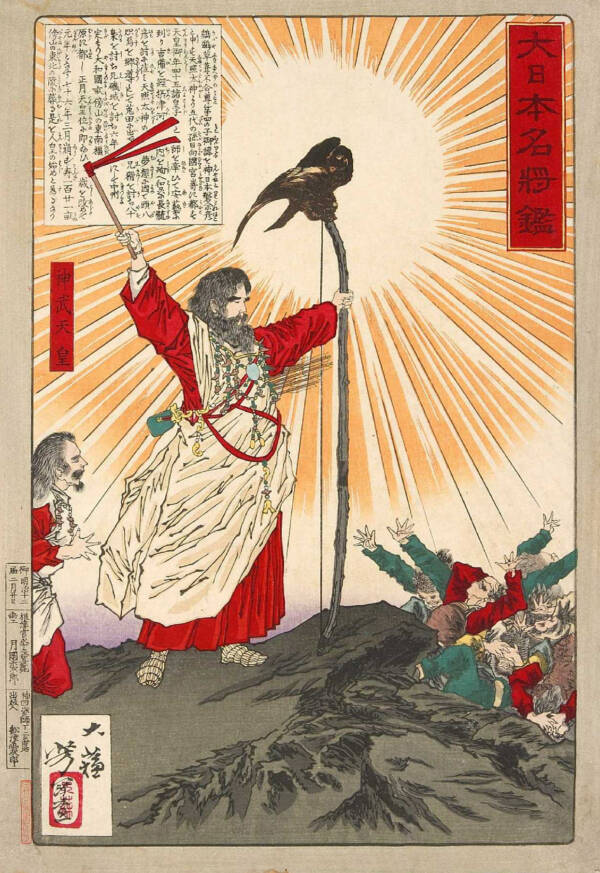

Wikimedia CommonsA 19th-century depiction of Emperor Jimmu, the legendary first emperor of Japan.

It’s hard to imagine the Japanese Empire without a Japanese emperor. Per the national mythology of Japan, the legendary first emperor, Jimmu, was the descendant of a sun goddess. February 11th, the date of Jimmu’s crowning in 660 B.C.E., is the country’s National Foundation Day.

Jimmu’s fabled role as the divine link between man, spirit, state, and nature, has served as the prototype for the emperor’s customary role in Shinto, a Japanese animist religion. As such, emperors like Jimmu and those who followed him have traditionally been revered by the public in Japan.

However, by the 12th century, Japan’s emperors were relegated to the background as a sequence of shoguns — military dictators — took over. But this system devolved into violence in the 15th century as Japan split into various provinces and rival lords, known as daimyo, fought for control.

In the early 17th century, the first Tokugawa shogun brought the fighting to an end at the cost of strict social control and near-total isolation from the outside world. For nearly 250 years, Japan remained in early modern stasis — a nation of farmers and merchants ruled by military nobility — until American Commodore Matthew Perry arrived in the country in 1853.

Armed with a small fleet of U.S. Navy ships, Perry demanded that Japanese ports reopen to outsiders. According to The U.S. Office of the Historian, Japanese policymakers noted how the British had forced China to open up to the world, and decided to work with Western powers to avoid being colonized by them, or subjugated by them in other ways.

At first, the Japanese were not excited about opening their borders. But before long, they started to take advantage of the new access they had to technology across the West — and the country began to modernize.

The Modernization Of Japan In The 19th Century

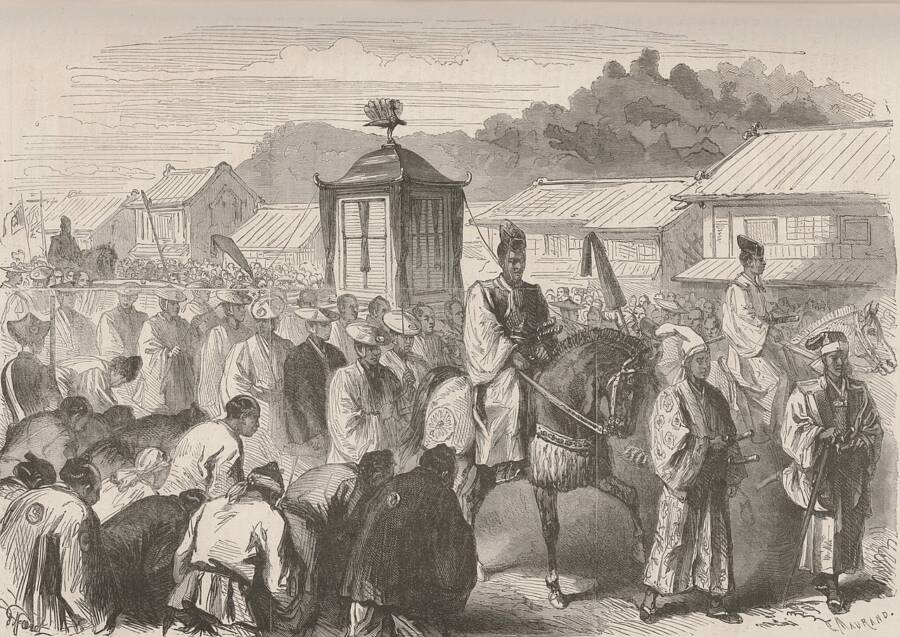

Public DomainEmperor Meiji’s 1868 journey from Kyoto to Tokyo, imagined by Le Monde Illustré.

Following Japan’s opening to the West, the Japanese launched one of the most rapid modernization efforts in history — and planted many seeds that would later mutate into Japanese war crimes during World War II.

After Emperor Meiji came to power in 1868, the shogunate was swiftly abolished and power shifted to the newly crowned emperor, marking the official beginning of the Japanese Empire. Meiji’s name came from the word “enlightened rule,” and the “Meiji Period” — or “Meiji Restoration” — sought to combine traditional Japanese values with modern advances.

As The Economist notes, Japanese officials traveled across the world to learn all they could about modern technology. They brought that back to Japan, leading to the construction of train tracks and telegraph lines. Still, the Japanese constitution of 1889 emphasized deep respect for the emperor, whose divine status was infused into the government.

One of the other key changes was the creation of a national army in 1871, maintained by mandatory three-year conscription for male citizens. Trained in new techniques and armed with the finest weaponry, this army was formed with the intention of self-protection. In practice, however, the army and the larger modernization of Japan set the stage for future atrocities.

How The Japanese Empire Established Itself As A Formidable World Power

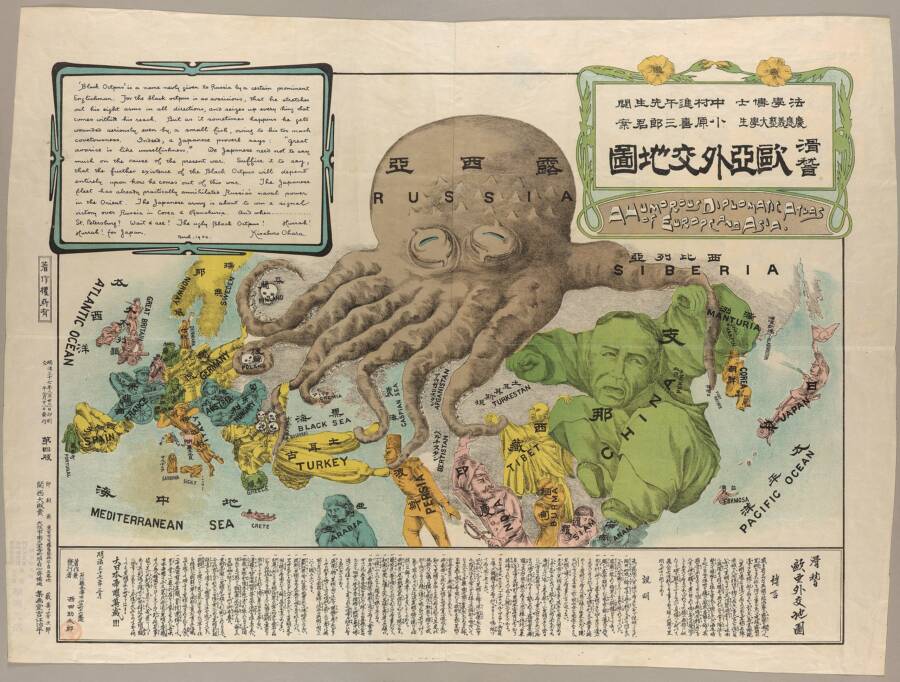

Wikimedia CommonsA satirical cartoon printed in Japan that showed Russia’s creeping influence over Europe and Asia. 1904.

Before long, Japan put its modern strength and military to the test. Starting in the 1870s, the Japanese Empire focused on Korea, which was largely under the control of China but rich in resources that Japan desired.

In 1894, increasing tensions between the two countries over Korea escalated into the First Sino-Japanese War. According to Britannica, foreign observers believed that China, with a larger army, would prevail in the fight. But Japan’s more modern forces fought their way to victory over the Chinese.

The Chinese were forced to sue for peace, and the resulting Treaty of Shimonoseki awarded great swaths of land to Japan. But that wasn’t enough for the Japanese. The South China Morning Post reports that Japanese assassins and Korean collaborators killed the Korean queen in 1895 because it seemed she might appeal to Russia to halt Japanese influence.

At this time, the Japanese Empire increasingly viewed Russia as a threat while they sought to expand their power throughout Asia.

In 1904, the two countries went to war after Russia refused to acknowledge Japan’s sphere of influence in Korea. Just like in the First Sino-Japanese War, foreign observers of the Russo-Japanese War underestimated Japanese forces. They triumphed over the Russians after just a year and a half.

Though short-lived and remembered mostly for Russia’s embarrassing defeat — which helped bring about the 1905 Russian Revolution — Japan’s victory over Russia established it as a force to be reckoned with.

Japanese Aggression In China Under Hirohito

Public Domain/Wikimedia CommonsThe Japanese fought in honor of Emperor Hirohito before and during World War II.

Having taken over Russian-built rail lines in China’s Manchuria region in 1905, Japan began eyeing opportunities for fuller control over Chinese territories. Following the collapse of the Qing dynasty in 1912 and the outbreak of political unrest, Japan worked with various “warlords” to better serve its aims. And during World War I, Japan briefly turned its attention to seizing islands in the Pacific that had once been German colonies.

In 1928, Emperor Hirohito — the grandson of Emperor Meiji — took the throne in Japan just as Chinese politician Chiang Kai-shek’s forces were taking control of China. But Chiang Kai-shek (a leader in China’s Nationalist Party) still faced a threat from Mao Zedong and his Communist forces. Meanwhile, both men faced threats from outside of the country as Japan searched for ways to increase its influence and power in China.

Then, in 1931, Japan set off an explosion next to its own rail line in Manchuria. Using the so-called Mukden Incident as an excuse to occupy the area, the Japanese created a puppet state of Manchukuo that was nominally ruled by the last Qing emperor but actually controlled by Japan.

Though the Japanese Empire’s aggression in China led to condemnation from the League of Nations — and Japan’s withdrawal from the peace-focused organization — Japan continued to conquer new territory.

The next year in 1932, according to the World War II Database, Japanese troops bombed Shanghai after Chinese troops supposedly “violated” rules that had been set by the Japanese. Despite international condemnation, Japan fought on, which led to an eventual ceasefire and the removal of Chinese troops in Shanghai. Back in Japan, Prime Minister Inukai Tsuyoshi was assassinated after trying to halt his country’s military actions.

Just five years later, tensions between the Japanese and Chinese escalated into the Second Sino-Japanese War. This would be followed by the Pacific Theater of World War II (though some argue that the Pacific War essentially began at the same time the Second Sino-Japanese War did). The ensuing battles would lead to some of the worst war crimes of the century.

The Second Sino-Japanese War And The Horrific Rape Of Nanking

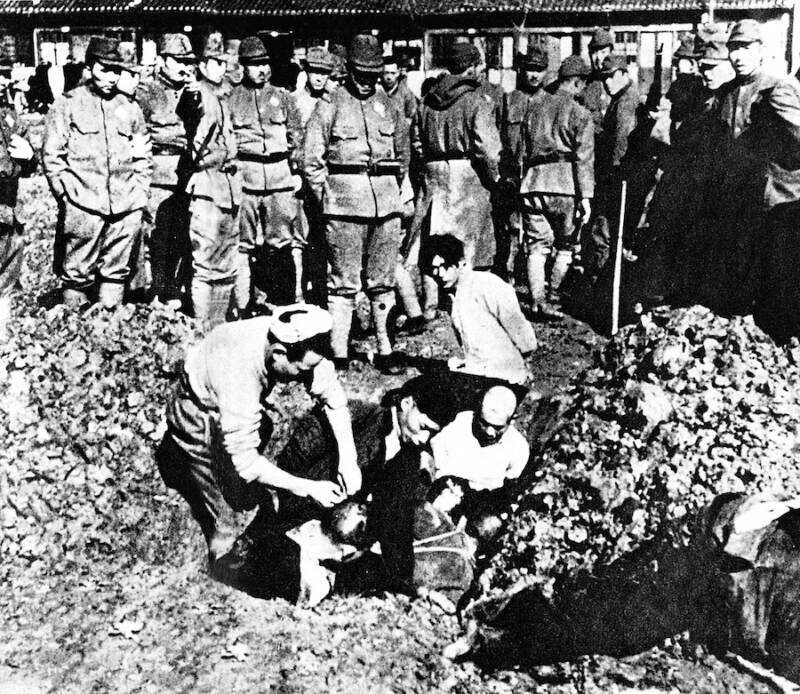

Public Domain/Wikimedia CommonsJapanese troops burying Chinese people alive during the Nanjing Massacre.

On July 7, 1937, a skirmish broke out between Japanese and Chinese troops on the outskirts of Beijing, leading to the beginning of the Second Sino-Japanese War. As History writes, various world powers — including the Soviet Union, Britain, France, the United States, and even Nazi Germany for a brief time — stepped up to support China during the conflict.

But the Japanese Empire fought on, often resorting to brutal tactics to obtain victory. Their determination to win by any means was gruesomely illustrated when Japanese troops marched on the city of Nanking.

The city — today better known as Nanjing — was then the capital of China, as well as one of its wealthiest cities. But when Nanking fell on December 13, 1937, forces under the command of Emperor Hirohito’s uncle, Prince Yasuhiko Asaka, surrounded the Chinese troops. The Japanese soldiers were allegedly commanded to “kill all the captives.” And then, the Rape of Nanking began.

What followed was a six-week massacre that may have killed over 300,000 people in the city. Up to 80,000 women and girls were raped, and many of these rape victims did not survive their assaults. Those who did live were often left mutilated. Indeed, the horrific stories of murder, rape, and torture are so numerous, one cannot possibly cover all of them in one article.

But one American surgeon’s diary entry, recorded in the book Eyewitnesses to Massacre, gives an idea of the carnage in Nanking:

“The slaughter of civilians is appalling. I could go on for pages telling of cases of rape and brutality almost beyond belief… Last night the house of one of the Chinese staff members of the university was broken into and two of the women, his relatives, were raped. Two girls, about 16, were raped to death in one of the refugee camps. In the University Middle School where there are 8,000 people the Japs came in ten times last night, over the wall, stole food, clothing, and raped until they were satisfied.”

It didn’t take long for word of these Japanese war crimes to quietly spread. One American reporter who had evacuated Nanking in the midst of the bloodshed tipped off The New York Times to what was happening as soon as he arrived safely in Shanghai. And an American priest, John Magee, managed to record some of the carnage in photographs and on film, including the large number of women killed by a bayonet to the genitals.

But while news of these atrocities soon outraged readers across the world, Japanese senior commanders decided that instead of preventing this kind of brutality from ever happening again, they’d simply hide it behind closed doors in brothels, which were specially created for the military.

Public Domain/Wikimedia CommonsA Chinese survivor of sex slavery, who was rescued from one of World War II-era Japan’s “comfort battalions” in 1945.

Another infamous story from the Nanjing Massacre is the “Contest to Kill 100 People Using a Sword.” As the name suggests, it was a competition between two Japanese officers, Toshiaki Mukai and Tsuyoshi Noda, to see who would be the first person to kill 100 Chinese people with a sword.

This was promoted as a heroic or sportsman-like competition to the Japanese public. According to China.org.cn, this is evidenced by the headline from the Tokyo Nichi Nichi Shimbun, which read: “‘Incredible Record’ — Mukai 106 — 105 Noda — Both 2nd Lieutenants Go Into Extra Innings.”

While it’s certainly disturbing to imagine an audience excitedly reading about mass murder, it was at least in part army propaganda, according to Noda. The truth was, Noda had no idea how many people he had killed, and many other Japanese soldiers were committing similar routine massacres, as noted in Katsuichi Honda’s 1999 book The Nanjing Massacre: A Japanese Journalist Confronts Japan’s National Shame. As Noda put it:

“Actually, I didn’t kill more than four or five people in hand-to-hand combat… We’d face an enemy trench that we’d captured, and when we called out, “Ni, Lai-Lai!” (You, come here!), the Chinese soldiers were so stupid, they’d rush toward us all at once. Then we’d line them up and cut them down, from one end of the line to the other. I was praised for having killed a hundred people, but actually, almost all of them were killed in this way.”

Wikimedia Commons The Tokyo Nichi Nichi Shimbun gleefully reporting on the score of the 100-man killing contest. 1937.

From accounts throughout the campaign in China, Japanese soldiers routinely slaughtered captured soldiers and civilians. As reported by Daqing Yang in an essay titled Diary of a Japanese Army Medical Doctor, 1937, this was an open secret. One doctor’s diary entry from 1937 described the machine-gunning of 80 “men and women of all ages” near Nanking.

Clearly acts of terrorism, these mass rapes and massacres can also be seen as a facet of genocidal violence perpetrated by the Japanese Empire. In many cases, the mutilated bodies of victims were left out for others to see, which undoubtedly had a horrific impact on the survivors left behind.

Among survivors — including women and girls who were kidnapped from China and other occupied countries and forced to become “comfort women” at Japanese military brothels — many were separated from their communities by personal shame or social stigma. Done enough times, in enough places, this was an attack against the foundations of culture itself.

Nowhere was this ambition to wipe out Chinese resistance more clearly stated than in a 1939 speech by Japanese Prime Minister Kiichirō Hiranuma, which echoed similar sentiments from Nazi leaders over the grim future for Slavic people: “I hope the intention of Japan will be understood by the Chinese so that they may cooperate with us. As for those who fail to understand we have no other alternative but to exterminate them.”

How The Japanese Empire Kept Marching On Throughout World War II

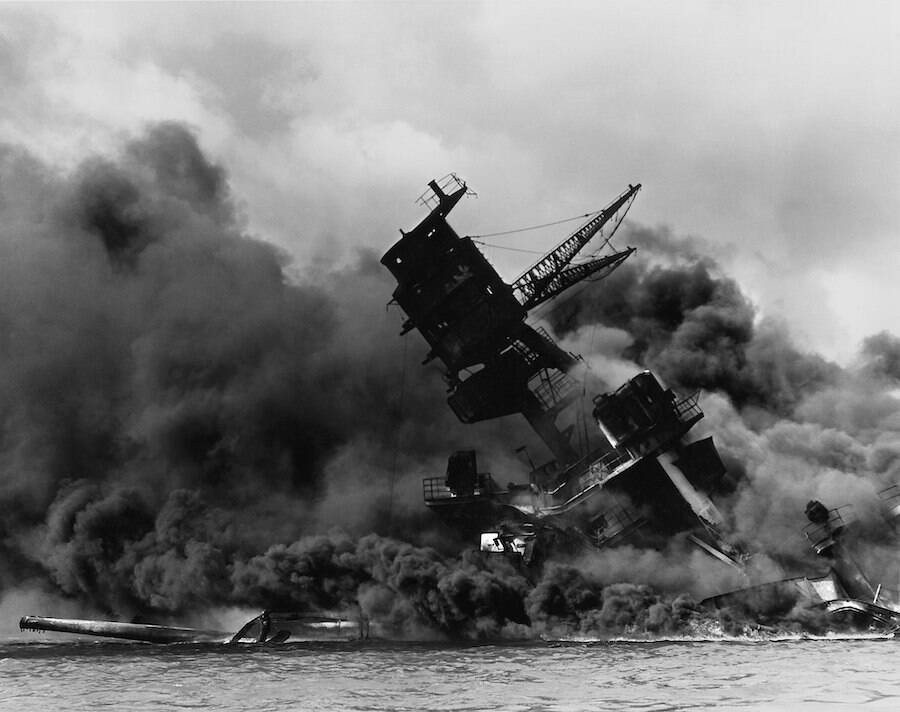

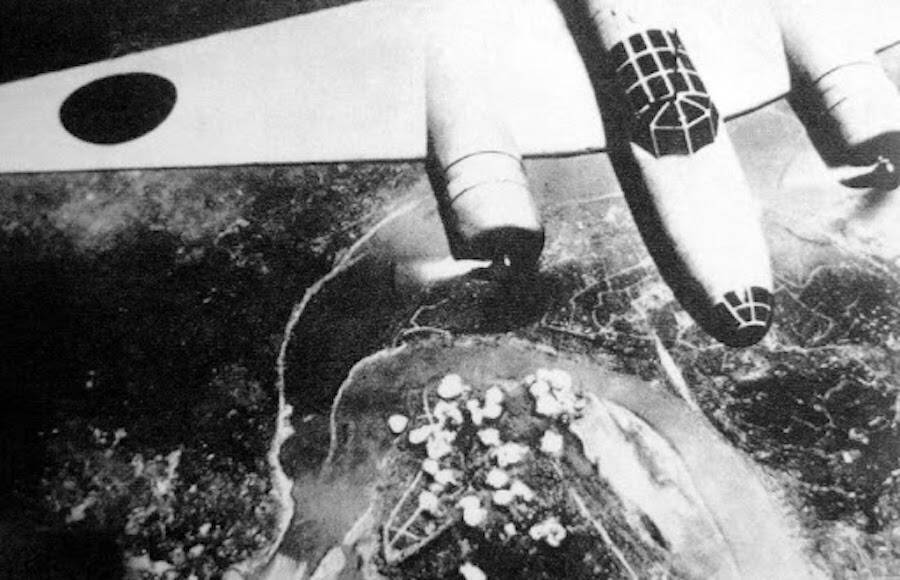

Public Domain/Wikimedia CommonsThe Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in Hawaii in 1941, which officially pulled the United States into World War II, ultimately led to the deaths of 2,403 Americans, including 68 civilians.

While capturing land and resources was important to Japan, getting the most out of these gains required considerable manpower and infrastructure. By the early 1940s, the Japanese had to supply, support, and maintain communications across thousands of miles, with not nearly a large enough population to supply the army they needed as well as the laborers.

Some Japanese troops turned to forced labor as a solution, luring or flat-out kidnapping people across Asia into back-breaking work. In Indonesia alone, as many as 10 million people were forced to work on numerous mining and infrastructure projects, according to Japan’s Quiet Transformation.

To keep Japanese soldiers entertained and satisfied on their breaks, military brothels were established at even the most remote outposts, filled with victims of kidnapping. Throughout the late 1930s and 1940s, up to 400,000 women and girls in Japanese-occupied parts of Asia were abducted and forced into sexual slavery for the Japanese military, according to NPR. Some of these rape victims were as young as eight years old.

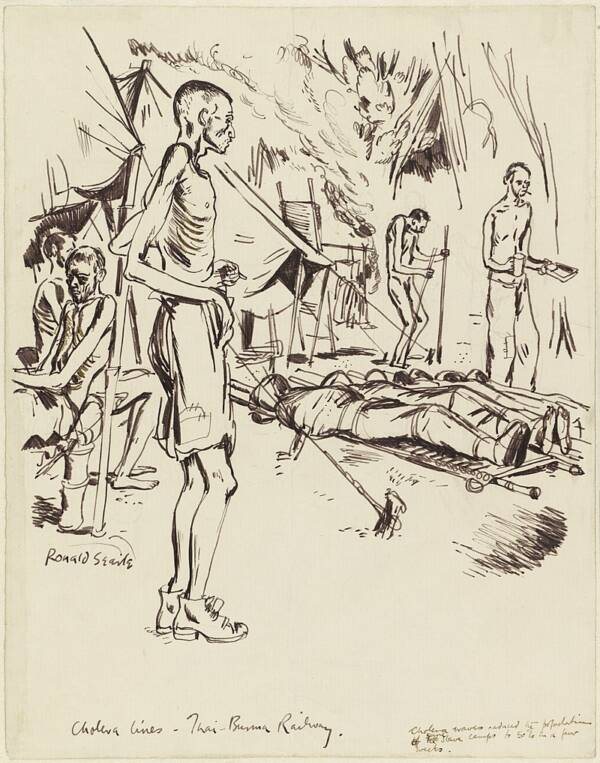

And in order to better move troops and supplies across its now-massive territory, the Japanese Empire required a 258-mile-long railway through Thailand and Burma during World War II. Hundreds of thousands of forced laborers and Allied prisoners of war were subjected to brutal labor with little to no food, and many of them died of starvation, exhaustion, or disease.

Public Domain/Wikimedia CommonsAmerican prisoners of war forced to carry their fallen comrades after the Bataan Death March. 1942.

Shockingly, some Japanese troops later claimed that some war crimes were carried out due to a lack of resources. For instance, in many cases, the mass executions of captured prisoners were considered to be more “practical” than keeping them alive and making sure they had enough essentials to live.

Sometimes, the Japanese believed that it was simply easier to shoot everyone, or, to save bullets, bayonet them or march them into the sea. In the infamous Bataan Death March of 1942, moving American and Filipino prisoners from one camp to another became a brutal exercise in thinning their numbers whenever prisoners could no longer keep up.

In other war crimes, however, it seems the cruelty had other practical purposes, like further advancing Japan’s scientific knowledge. Certain prisoners of war and civilians — most of whom were Chinese — were transported to facilities like Unit 731, where Japanese medical officers performed inhumane experiments on human beings before killing them.

In 1995, a former medical assistant from a Japanese Army unit stationed in China during World War II described his experience of dissecting a man alive for the first time: “When I picked up the scalpel, that’s when he began screaming. I cut him open from the chest to the stomach, and he screamed terribly, and his face was all twisted in agony. He made this unimaginable sound, he was screaming so horribly. But then finally he stopped.”

According to the former medical assistant, the victim was a 30-year-old Chinese “prisoner” who had been intentionally infected with the plague as part of a horrific research project carried out by Japan during World War II. The vivisection was just the final step of this man’s role as an unwilling test subject — he was cut open to see what the plague had done to his insides.

The assistant also rationalized the lack of anesthetic, as the researchers were worried that the substance would affect the final results.

Violence As Propaganda And Indoctrination

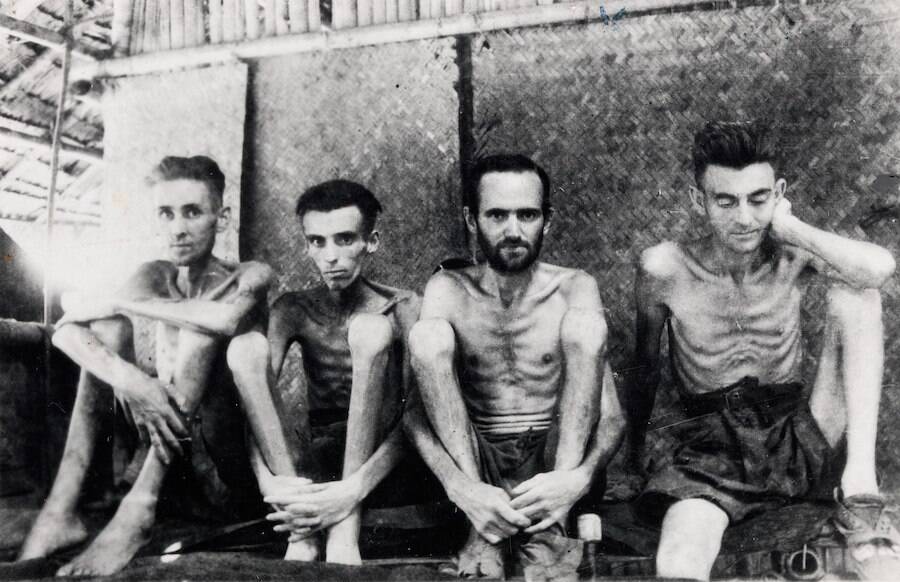

Wikimedia CommonsAustralian and Dutch prisoners of war, held by the Japanese in Thailand. 1943.

One lingering accusation heard most often by American World War II veterans is that the Japanese were the worst to their captives of any Axis Power. Upon examination, there does seem to be some truth here. According to the MacArthur Memorial Education Programs, prisoners of war suffered a 4 percent death rate in Europe and a 27 percent death rate in the Pacific.

As explained in a text issued by the Japanese government during the war, “An Investigation of Global Policy with the Yamato Race as Nucleus,” the Japanese considered themselves a chosen (and superior) people under a divine emperor. This notion was explicitly tied to eugenics.

As it turns out, the unscientific Yamato Race Theory is remarkably similar to Nazi Race Theory, including personal virtues and ideals that make up a true Yamato Warrior. Part of this ethos includes the Japanese prohibition against surrender, or as it is sometimes called, “death before dishonor.”

Wikimedia Commons“Cholera Lines,” a sketch of life in a Japanese prison camp by a former prisoner of war.

While, on one hand, this resulted in the kamikaze pilots, who made deliberate suicidal crashes into enemy vessels, it also promoted a valuable idea. If a true Japanese warrior would never surrender, and never allow themselves the shame of being taken prisoner, why should they have any sort of respect for the kind of person that would? By extension, why should they have any respect for that person’s family, possessions, or even their life?

This likely helped enable Japanese soldiers to commit crimes against other races and groups of people. And when carried out against Westerners specifically, it helped confirm their own belief in their superiority to colonial powers. Whenever Japanese troops displayed Western prisoners of war to the public, they made sure they looked as pathetic as possible, typically by starving them or by denying them necessary medical treatment.

In one particularly brutal case of Japanese war crimes against Western prisoners, staff members at a Japanese university dissected downed American pilots — while they were still alive — as reported by the Daily Mail.

And in another revealing anecdote, a Japanese soldier tasked with beheading an American prisoner recounted how he tried to swing the sword three times before going through with it — when he thought about the emperor and removed himself and the prisoner from the equation.

Japanese War Crimes As A Form Of Brutal Group Bonding During World War II

Wikimedia CommonsJapanese soldiers shooting Sikh prisoners of war during World War II.

While there are few reports of the internal monologues of the Japanese soldiers who personally carried out war crimes, it is reported that soldiers were told that the same would be done to them if they were ever captured during World War II. This potentially helped motivate them to act as brutally as possible in order to avoid being treated that way themselves.

But the fear of capture alone may not have been a powerful enough motivator to perpetrate these atrocities. After all, for most people, it takes a psychological toll to kill someone, especially if torture is involved.

In Nazi Germany, one of the reasons for the creation of the Nazi death camps was that the members of the mobile killing squads known as the Einsatzgruppen were reportedly suffering from “mental strain.”

However, what the Japanese Empire seems to have understood, at least implicitly, is that having someone enact violence on another person — particularly, if the subject is young, male, and in a group of other young males — can be a powerful bonding exercise. (A modern-day instance of this type of violence might be deadly hazing incidents at universities.)

Perhaps the most gruesome example of bonding among some Japanese troops is the cannibalism that took place during World War II. Though most soldiers who turned to cannibalism during the war later claimed that they were starving and had no choice but to eat people, there were at least a few incidents of troops cannibalizing enemy troops, civilians, and even each other for spiritual or sporting purposes. In some cases, officers ordered their underlings to eat human flesh to give them a “feeling of victory.”

It’s clearly devastating that an entire generation of Japanese people was encouraged to commit horrific violence against other groups. But some have wondered whether this coercion on the part of the Japanese government and high-ranking military leaders is yet another crime all its own.

The prohibition of surrender and the “death before dishonor” mentality of Japanese troops, and in some cases, civilians, could be seen as an effective suicide pact. This was painfully clear in Okinawa, the last major battle of World War II, where Okinawan civilians were encouraged — and ordered — by soldiers in the Japanese Army to die by suicide rather than being taken captive by American soldiers, according to The New York Times.

As it turns out, one of the generals who forced the devastating fight to the death during the Battle of Okinawa — costing the lives of 94,000 Okinawan civilians — was the same one who may have ordered the Nanjing Massacre.

The Legacy Of The Japanese Empire’s Atrocities

Wikimedia CommonsIt wasn’t until 2002 that a Tokyo court finally acknowledged that World War II-era Japan had engaged in biological warfare against Chinese civilians by spreading diseases like the plague, leading to as many as 300,000 deaths.

Though most people in the West understand the magnitude of the Nazi Holocaust and the European Theater in modern times, few grasp the extent of Japan’s brutality during World War II. Much like Nazi Germany, the Japanese Empire was one of the most genocidal in world history.

However, in the years since the war ended, Germany has made strides to confront its history. This includes prosecuting former Nazis, erecting memorials to Holocaust victims, preserving death camps, and making it illegal to deny that the systematic mass murder of 6 million Jews happened. But Japan has done comparatively little to address its war crimes.

Today, many Americans are horrified when they learn about this. But the United States actually played a large role in why Japan wasn’t forced to answer for its atrocities during World War II. Not only did U.S. authorities help cover up these war crimes, but they also granted immunity to many high-ranking Japanese generals in exchange for any data they collected.

One of the most infamous examples is Shiro Ishii, the Japanese Army medical officer behind Unit 731. Eager to learn the results of Ishii’s barbaric research on human beings — without actually performing the experiments themselves — American authorities agreed not to charge him with war crimes as long as he shared the detailed results of his program.

Wikimedia CommonsEven today, some in Japan downplay or even outright deny the atrocities of World War II-era Japan.

Emperor Hirohito, the man who the nation had spent years fighting for, also escaped justice. This was largely due to U.S. General Douglas MacArthur, who oversaw the Allied occupation of Japan in the aftermath of the war. He firmly believed that executing an emperor — who many Japanese people still saw as a “living god” — would make the country ungovernable.

Another reason why Japan’s atrocities didn’t get as much attention as Germany’s had to do with their trials. Thanks, in part, to Japan’s strategic importance against the Soviets in the emerging Cold War, the war crimes trials in Japan were a different affair than the Nuremberg trials.

Whereas the prosecution of the Nazis had been international, detailing crimes committed against multiple nations, the Japanese were prosecuted in different trials, years apart, by the United States and the Soviet Union. Cold War interests informed who was prosecuted, who was left running the country, and what the public was allowed to know.

As a result, many of the crimes were never fully revealed during the lifetimes of most of the people who were involved, and never really answered for. By 1958, nearly all of the imprisoned Japanese war criminals had been released — denying the world, and Japan itself, the full and ugly picture.

Sadly, the tendency to downplay war crimes in Japan continues even today. In 2022, when Japan’s Prime Minister Fumio Kishida marked the end of World War II in August, he didn’t mention Japanese aggression and instead said that Japan would “stick to our resolve to never repeat the tragedy of the war.” And as for Emperor Naruhito — the grandson of Hirohito — he simply expressed his “deep remorse” over Japan’s actions during the war.

After reading about the history of the Japanese Empire, learn about one of the most famous conflicts of the Pacific Theater: the Battle of Iwo Jima. Then, check out the most striking pictures from Japan’s imperial era.