Shiro Ishii ran Unit 731 and performed cruel experiments on prisoners until he was apprehended by the U.S. government — and granted full immunity.

A few years after World War I, the Geneva Protocol prohibited the use of chemical and biological weapons during wartime in 1925. But that didn’t stop a Japanese army medical officer named Shiro Ishii.

A graduate of Kyoto Imperial University and a member of the Army Medical Corps, Ishii was reading about the recent bans when he got an idea: If biological weapons were so dangerous that they were off-limits, then they had to be the best kind.

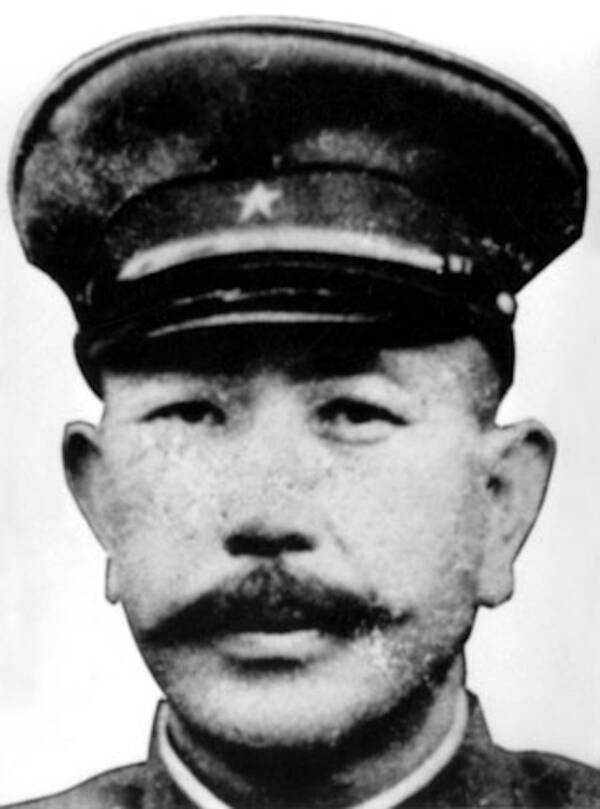

Wikimedia CommonsShiro Ishii is often compared to the infamous Nazi doctor Josef Mengele, but he arguably had even more power over his human experiments — and did far more monstrous scientific research.

From that point on, Ishii dedicated his life to the deadliest kinds of science. His germ warfare and inhumane experiments aimed to place the Empire of Japan on a pedestal above the world. This is the story of General Shiro Ishii, Japan’s answer to Josef Mengele and the evil “genius” behind Unit 731.

Shiro Ishii: A Dangerous Youth

Born in 1892 in Japan, Shiro Ishii was the fourth son of a wealthy landowner and sake maker. Rumored to have a photographic memory, Ishii excelled in school to the point that he was labeled a potential genius.

Ishii’s daughter Harumi would later muse that her father’s intelligence might have led him to be a successful politician if he had chosen to go down that path. But Ishii chose to join the military at an early age, showing boundless love for Japan and its emperor all along the way.

Wikimedia CommonsFrom an early age, Shiro Ishii was believed to be a genius.

An atypical recruit, Ishii did well in the military. Standing six feet tall — well above the height of the average Japanese man — he boasted a commanding appearance early on. He was known for his spotlessly clean uniforms, his meticulously groomed facial hair, and his deep, powerful voice.

During his service, Ishii discovered his real passion — science. Specifically interested in military medicine, he worked tirelessly toward the goal of becoming a doctor in the Imperial Japanese Army.

In 1916, Ishii was admitted to the Medical Department of Kyoto Imperial University. In addition to learning both the best medical practices of the time and proper laboratory procedures, he also developed some strange habits.

He was known for keeping bacteria in petri dishes as “pets.” And he also had a reputation for sabotaging other students. Ishii would work in the lab at night after the other students had already cleaned up — and use their equipment. He would purposely leave the equipment dirty so the professors would discipline other students, which led them to resent Ishii.

But while the students knew what Ishii had done, he was apparently never punished for his actions. And if the professors somehow knew what he was doing, it almost seemed as if they were rewarding him for it.

It’s perhaps a sign of his growing ego that shortly after reading about biological weapons in 1927, he decided that he would become the best in the world at making them.

Shiro Ishii’s Immodest Proposal

Wikimedia CommonsSpecial Naval landing forces of the Imperial Japanese Navy prepare to advance during the Battle of Shanghai in August 1937 — with gas masks firmly in place.

Shortly after reading the initial journal article that inspired him, Shiro Ishii began to push for a military arm in Japan that focused on biological weapons. He even directly pleaded with top commanders.

To truly grasp the scale of his confidence, consider this: Not only was he a lower-ranking officer suggesting military strategy, but he was also proposing the direct violation of relatively new international laws of war.

At the crux of Ishii’s argument was the fact that Japan had signed the Geneva agreements, but had not ratified them. Since Japan’s stance on the Geneva agreements was technically still in limbo, there was perhaps some wiggle room that would allow for them to develop bioweapons.

But whether Ishii’s commanders lacked his vision or nebulous grasp of ethics, they were skeptical of his proposal at first. Never one to take no for an answer, Ishii asked for — and ultimately received — permission to take a two-year research tour of the world to see what other countries were doing in terms of biological warfare in 1928.

Whether this signaled legitimate interest on the part of the Japanese military or simply an effort to keep Ishii happy is unclear. But either way, after his visits to various facilities across Europe and the United States, Ishii returned to Japan with his findings and a revised plan.

A Receptive Audience

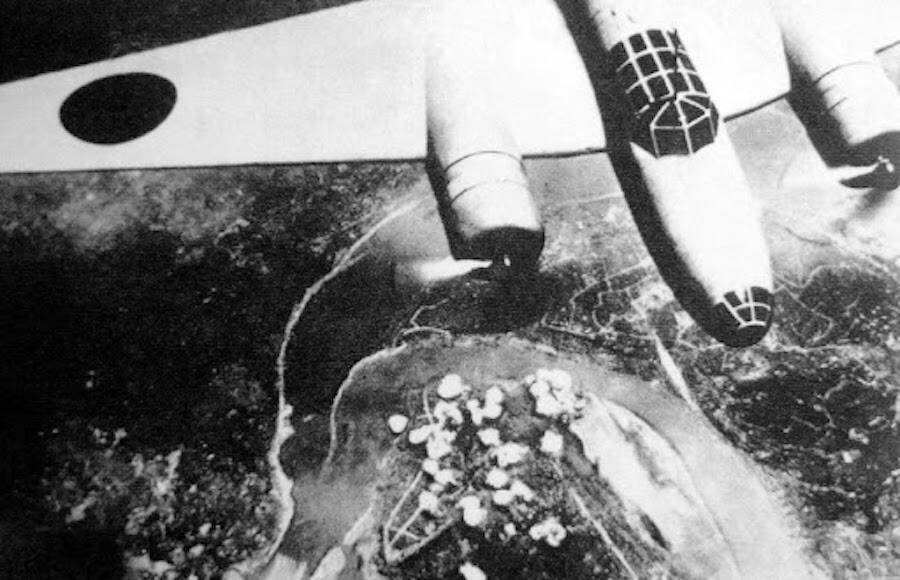

Wikimedia CommonsThe Japanese soldiers bombed Chongqing, China from 1938 to 1943.

Despite the Geneva Protocol, other countries were still researching biological warfare. But, out of either ethical concerns or fear of discovery, no one had yet made it a priority.

So in the years preceding World War II, Japanese troops began to seriously consider investing their resources in this controversial weaponry — with the goal that their battle techniques would surpass all other countries on Earth.

By the time Ishii returned to Japan in 1930, a few things had changed. Not only was his country on track to wage war against China, nationalism as a whole in Japan burned a little brighter. The old country slogan of “a wealthy country, a strong army” was echoing louder than it had in decades.

Ishii’s reputation had also grown. He was appointed professor of immunology at the Tokyo Army Medical School and given the rank of major. He also found a powerful supporter in Colonel Chikahiko Koizumi, who was then a scientist at the Tokyo Army Medical College.

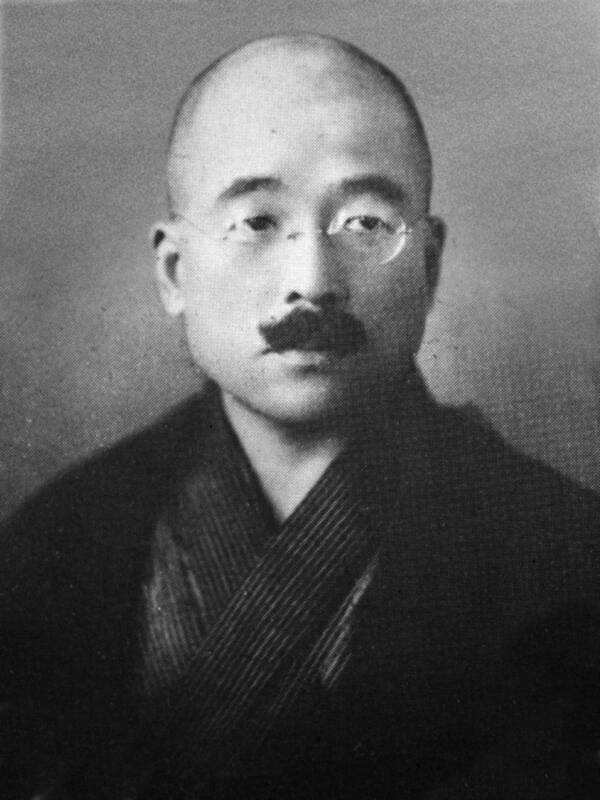

Wikimedia CommonsJapanese army surgeon Chikahiko Koizumi. After World War II, he came under suspicion for being a war criminal, but he committed suicide before he could be properly investigated.

A veteran of World War I, Koizumi oversaw research into chemical warfare beginning in 1918. But around this time, he almost died in a lab accident after being exposed to a chlorine gas cloud without a gas mask. After his full recovery, he continued his research — but his superiors placed a low priority on his work at the time.

So it’s no surprise that Koizumi saw himself reflected in Shiro Ishii. At the very least, Koizumi saw someone similar enough to him who shared his vision for Japan. As Koizumi’s star continued to rise — first to Dean of the Tokyo Army Medical College, then to Army Surgeon General, then to Japan’s Minister of Health — he made sure that Ishii moved up along with him.

For Ishii’s part, he certainly enjoyed the praise and promotions, but nothing seems to have been more important to him than his own self-aggrandizement.

Ishii’s public work consisted of researching microbiology, pathology, and vaccine research. But as all those in the know understood, this was only a small part of his actual mission.

Unlike his student years, Ishii was rather popular as a professor. The same personal charisma and magnetism that had won over his teachers and commanders also worked on his students. Ishii often spent his nights out drinking and visiting geisha houses. But even while inebriated, Ishii was more likely to go back to his studies than to go to bed.

This behavior is telling on two counts: It shows the kind of obsessive man Ishii was, and it explains how he was able to persuade others to help him with his deranged experiments after he began working in China.

A Secret, Sinister Facility

Xinhua via Getty ImagesUnit 731 personnel conduct a bacteriological trial upon a test subject in Nongan County of northeast China’s Jilin Province. November 1940.

Following the invasion of Manchuria in 1931 and the establishment of the puppet client state Manchukuo shortly thereafter, Japan utilized the region’s resources to fuel its industrialization efforts.

Like the attitudes of Americans during the “Manifest Destiny” period of expansion, many Japanese soldiers saw the people living in the area as obstacles. But to Shiro Ishii, these residents were all potential test subjects.

According to Ishii’s theories, his biological research would require different types of facilities. For instance, he established a biological weapons facility in Harbin, China, but quickly realized that he wouldn’t be able to freely conduct involuntary human research in that city.

So he simply began to put together another secret facility that was about 100 kilometers south of Harbin. The 300-home village of Beiyinhe was razed to the ground to make way for the site, and local Chinese laborers were drafted to construct the buildings.

Here, Shiro Ishii developed some of his barbaric techniques, foreshadowing what would come in the notorious Unit 731.

Wikimedia CommonsUnit 731’s Harbin facility was built on Manchurian land conquered by Japan.

The sparse records from the Beiyinhe facility offer a sketch of Ishii’s work there. With up to 1,000 prisoners crammed into the facility, the test subjects were a mixed group of underground anti-Japanese workers, guerrilla bands who harassed the Japanese, and innocent people who unfortunately got caught in a roundup of “suspicious persons.”

A common early experiment was drawing blood from prisoners every three to five days until they were too weak to go on, and then killing them with poison when they were no longer considered valuable to research. Most of these subjects were killed within a month after their arrival, but the number of total victims in the facility remains unknown.

In 1934, a prisoner rebellion broke out as the soldiers celebrated the Mid-Autumn Festival. Taking advantage of the guards’ drunkenness and the relatively lax security, some 16 prisoners were able to successfully escape. This is the main reason why we know what we do about that facility.

Despite the extreme risk to the security and secrecy of the operation, it’s possible that experiments continued at that site as late as 1936, before it was officially shut down in 1937.

Ishii, for his part, did not seem to mind the closure. He was already getting started with another facility — which was far more sinister.

The Josef Mengele Of Japan

Xinhua via Getty ImagesUnit 731 researchers conduct bacteriological experiments on captive child subjects in Nongan County of northeast China’s Jilin Province. November 1940.

Shiro Ishii is often compared to Josef Mengele, the German doctor known as the “Angel of Death,” who conducted sinister experiments in Nazi-occupied Poland.

The infamous Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp was a complex that killed its prisoners as part of its design. While many victims were executed in gas chambers, others were reserved for Mengele and his twisted medical experiments.

As an SS officer and member of the Nazi elite, Mengele had the authority to determine the fitness of prisoners, recruit imprisoned medical professionals as assistants, and force inmates into becoming his test subjects.

But unlike Ishii, Mengele was more limited in his power over the camp and in the effectiveness of his research. Auschwitz had been built to produce rubber and oil, and Mengele used the environment to conduct pseudoscience. His work fell under the guise of genetics, but it was often little more than pointless and cruel acts of sadism.

In many ways, Ishii had more control over his human subjects. His research was also more scientific — and monstrous. Just about all the horrors that occurred in the facilities had been thought up by Ishii — with the intention of turning human beings into data.

Expanding and building upon his earlier efforts, Ishii designed Unit 731 to be a self-sufficient facility, with a prison for his human subjects, an arsenal for making germ bombs, an airfield with its own air force, and a crematorium to dispose of human remains.

In another part of the facility were the dormitories for Japanese residents, which included a bar, library, athletic fields, and even a brothel.

But nothing at the complex could compare to Ishii’s house in Harbin, where he lived with his wife and children. A mansion left over from the period of Russian control over Manchuria, it was a grand structure that was remembered fondly by Ishii’s daughter Harumi. She even likened it to the home in the classic film Gone With The Wind.

Shiro Ishii And The Experiments At Unit 731

Xinhua via Getty ImagesThe frostbitten hands of a Chinese person who was taken outside in winter by Unit 731 personnel for an experiment on how to best treat frostbite. Date unspecified.

If you know the name Unit 731, then you probably have some idea of the horrors that unfolded at Ishii’s facility — believed to be set up around 1935 in Pingfang. Despite decades of cover-up, stories of the cruel experiments that took place there have spread like wildfire in the age of the internet.

However, for all the discussion of freezing limbs, vivisections, and high-pressure chambers, the horror that tends be ignored is Ishii’s inhumane reasoning behind these tests.

As an army doctor, one of Ishii’s primary goals was the development of battlefield treatment techniques that he could use on Japanese troops — after learning just how much the human body could handle. For example, in the bleeding experiments, he learned how much blood the average person could lose without dying.

But at Unit 731, these experiments kicked into high gear. Some experiments involved simulating real-world conditions.

For example, some prisoners were placed in pressure chambers until their eyes popped out so that they could demonstrate how much pressure the human body could withstand. And some prisoners were injected with seawater to see if it could work as a replacement for a saline solution.

The most horrifying example touted around the internet – the frostbite experiment — was actually pioneered by Yoshimura Hisato, a physiologist assigned to Unit 731. But even this test had a practical battlefield application.

Unit 731 researchers were able to prove that the best treatment for frostbite was not rubbing the limb — the traditional method up until that point — but instead immersion in water a bit warmer than 100 degrees Fahrenheit (but never hotter than 122 degrees Fahrenheit). But the way they came to this conclusion was horrific.

Unit 731 researchers would lead prisoners outside in freezing weather and leave them with exposed arms that were periodically drenched with water — until a guard decided that frostbite had set in.

Testimony from a Japanese officer revealed that this was determined after the “frozen arms, when struck with a short stick, emitted a sound resembling that which a board gives when it is struck.”

When the limb was struck, this sound would apparently let the researchers know that it was sufficiently frozen. The frostbite-affected limb was then amputated and taken to the lab for study. More often than not, the researchers would then move on to the prisoners’ other limbs.

When prisoners were reduced to heads and torsos, they were then handed over for plague and pathogen experiments. Brutal as it was, this process bore fruit for Japanese researchers. They developed an effective frostbite treatment several years ahead of other researchers.

As with Mengele, Ishii and the other Unit 731 doctors wanted a wide sample of subjects to study. According to official accounts, the youngest victim of a temperature-changing experiment was a three-month-old baby.

The Brutality Of Weapons Testing

Xinhua via Getty ImagesA Unit 731 doctor operates on a patient that is part of a bacteriological experiment. Date unspecified.

Weapons testing at Unit 731 took several distinct forms. As with medical research, there were “defensive” tests of new equipment, such as gas masks.

Researchers would force their prisoners to test out the effectiveness of certain gas masks in order to find the best kind among the pack. Although unconfirmed, it is believed that similar testing led to an early version of the bio-hazard protection suit.

In terms of offensive weapons tests, these tended to fall under two different categories. The first was the deliberate infection of prisoners to study disease effects and to select suitable candidates for weaponization.

In order to better understand the impacts of each disease, researchers did not provide prisoners with treatment and instead dissected or vivisected them so that they could study the impact of the diseases on the internal organs. Sometimes, they were still alive while they were being cut open.

In a 1995 interview, one anonymous former medical assistant in a Japanese Army unit in China revealed what it was like to cut open a 30-year-old man and dissect him alive — without any anesthetic.

“The fellow knew that it was over for him, and so he didn’t struggle when they led him into the room and tied him down,” he said. “But when I picked up the scalpel, that’s when he began screaming.”

He continued, “I cut him open from the chest to the stomach, and he screamed terribly, and his face was all twisted in agony. He made this unimaginable sound, he was screaming so horribly. But then finally he stopped. This was all in a day’s work for the surgeons, but it really left an impression on me because it was my first time.”

The second type of offensive weapons testing involved the actual field testing of various systems that dispersed diseases. These were used against prisoners within the camp — and against civilians outside of it.

Ishii was diverse in his exploration of disease dispersal methods. Inside the camp, prisoners infected with syphilis would be forced to have sex with other prisoners who weren’t infected. This would help Ishii observe the onset of the disease. Outside the camp, Ishii gave other prisoners dumplings that were injected with typhoid and then released them so they could spread the disease.

He also passed out chocolates filled with anthrax bacteria to local children. Since many of these people were starving, they often didn’t question why they were receiving this food and unfortunately assumed it was just an act of kindness.

Sometimes, Ishii’s men would use air raids to drop innocuous items like wheat and rice balls and strips of colored paper above nearby cities. It was later discovered that these items were infected with deadly diseases.

But as horrific as these attacks were, it was Ishii’s bombs that truly placed him at the top of all other biological weapons researchers.

A “Gift” To Mankind

Xinhua via Getty ImagesJapanese personnel in protective suits carry a stretcher through Yiwu, China during Unit 731’s germ warfare tests. June 1942.

Ishii’s plague bombs carried an unusual payload. Instead of the usual metal containers, they would use containers made of ceramic or clay so that they would be less explosive. That way, they would be able to properly release plague-infected fleas on countless people.

Unable to improve off of the traditional means of spreading the “Black Death,” Ishii decided to skip the rat middleman. When his bombs exploded, the surviving fleas would quickly escape, seeking out hosts to feed on and spread the disease.

And that’s exactly what happened in China during World War II. Japan dropped these bombs on both combatants and innocent civilians in multiple towns and villages.

But Ishii’s master plan, “Operation Cherry Blossoms at Night,” intended to use these weapons against the United States.

If this plan would’ve succeeded, about 20 of the 500 new troops who arrived in Harbin would’ve been taken toward southern California in a submarine. They would’ve then manned an onboard plane and flown it to San Diego. And plague bombs would’ve then been dropped there in September 1945.

Thousands of disease-riddled fleas would’ve been deployed, as the troops took their own lives by crashing somewhere onto American soil.

However, America’s atomic bombings happened before this plan came to fruition. And the war ended before the operation was even fully mapped out. But ironically enough, it was America’s interest in Ishii’s research that ultimately saved his life.

In August 1945, shortly after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the order came to destroy all evidence of the activities at Unit 731. Shiro Ishii sent his family ahead by railroad, remaining behind until his infamous facilities were destroyed.

The exact number of people killed by Unit 731 and its related programs remains unknown, but estimates usually range from about 200,000 to 300,000 (including the biological warfare operations). As for deaths due to human experimentation, that estimate typically ranges around 3,000. By the end of the war, any remaining prisoners were speedily killed off.

Although Ishii was also ordered to destroy all documentation, he carried some of his lab notes out of the facility with him before going into hiding in Tokyo. Then, the American occupation authorities paid him a visit.

Throughout the war, vague reports from China about unusual outbreaks and “plague bombs” had not been taken very seriously until the Soviets took Manchuria from the Japanese. By that point, the Soviets knew enough to have a vested interest in finding and securing General Ishii to “interview” him about his infamous research.

For better or for worse, the Americans got to him first. According to Ishii’s daughter Harumi, the American officers used her as a transcriber as they interrogated her father about his work.

At first, he played coy, pretending not to know what they were talking about. But after he secured immunity, protection from the Soviets, and 250,000 yen as payment, he began to talk.

All told, he’d revealed 80 percent of his data to the United States by the time of his death. Apparently, he took the other 20 percent to his grave.

A Deal With The Devil

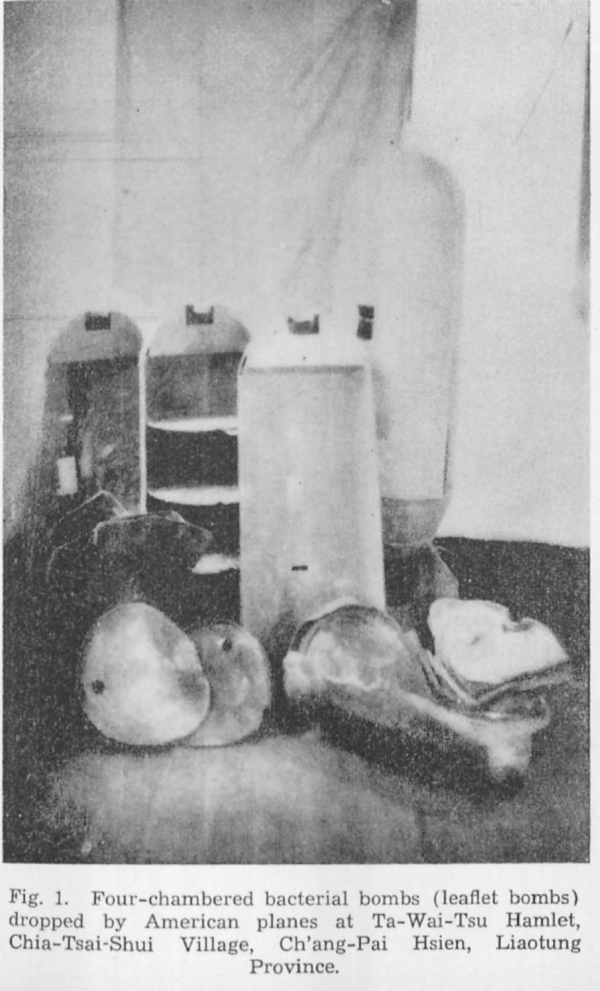

Wikimedia CommonsUnit 731 bombs on display at a museum on the site of where the Harbin bioweapon facility used to be.

In order to protect Ishii and maintain a monopoly on his research, the United States kept its word. The crimes of Unit 731 and other similar organizations were suppressed, and at one point they were even labeled “Soviet Propaganda” by American authorities.

And yet, a “top secret” cable from Tokyo to Washington in 1947 revealed: “Experiments on humans were … described by three Japanese and confirmed tacitly by Ishii. Ishii states that if guaranteed immunity from ‘war crimes’ in documentary form for himself, superiors, and subordinates, he can describe program in detail.”

To put it plainly, American authorities were eager to learn the results of experiments that they weren’t willing to perform themselves. That’s why they granted him immunity.

Although some of the research from Ishii was valuable, American authorities didn’t learn nearly as much as they thought they would. And yet they kept their end of the bargain. Shiro Ishii lived out the rest of his days in peace until he died of throat cancer at the age of 67.

Years after the agreement, North Korea made a startling allegation that the United States had dropped plague bombs on them during the Korean War.

And so a group of scientists from France, Italy, Sweden, the Soviet Union, and Brazil — led by a British embryologist — toured the affected areas to collect samples and issue a verdict in the 1950s.

Wikimedia CommonsA page from the International Scientific Commission for the Facts Concerning Bacterial Warfare in China and Korea. Allegations that America used biological warfare during the Korean War remain controversial to this day.

Their conclusion was that germ warfare had indeed been used as North Korea claimed. Officially, this is also “Soviet Propaganda,” according to the United States. Or is it?

With a clear answer still missing, we are left with uncomfortable questions. Consider the following: In 1951, a now-declassified document showed that the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff issued orders to begin “large scale field tests… to determine the effectiveness of specific BW [bacteriological warfare] agents under operational conditions.” And in 1954, Operation “Big Itch” dropped flea bombs at the Dugway Proving Ground in Utah.

With that in mind, what is more likely? Are these actions coincidental to the Chinese and Soviets using part of the truth that they knew in an attempt to embarrass the Americans? Or, did someone secretly give the order to bring Shiro Ishii and his men out of retirement?

In any case, one thing is clear. Shiro Ishii never faced justice and died a free man in 1959 — all thanks to the United States deal with the Devil.

After reading about Shiro Ishii, the unhinged mind behind Unit 731, learn the full story of Operation “Cherry Blossoms at Night.” For a glimpse of what the operation may have looked like, check out the mysterious “Battle of Los Angeles” that may have been started by a Japanese balloon bomb.