Months after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Los Angeles residents woke up to sirens, explosions, and searchlights across the skies. Was the "Battle of Los Angeles" a shadowy government coverup or an embarrassing military blunder?

Wikimedia CommonsScenes from the “Battle of Los Angeles,” as citizens grappled with the aftermath.

At 2:25 a.m. on Feb. 25, 1942, the people of Los Angeles woke up to sirens. Every light in the city was extinguished. Spotlights searched the sky above as bombs exploded overhead, filling the horizon with smoke and scattering debris across the city.

Dressed in their pajamas, Angelenos stood on their porches, squinting upward to see the battle breaking out above them. In the streets, cars and trollies remained frozen where they had been as the alarms sounded, the thunderous roar of more than 1,400 rounds of ammunition exploding against the still night sky.

Finally, the “all clear” was given at 7:21 a.m. In its wake, the air raid left five dead, many injured, and houses damaged by falling shells. What it did not leave, however, was any downed enemy aircraft.

That’s because there hadn’t been enemy aircraft to begin with.

Regardless, the “Battle of Los Angeles,” or “The Great Los Angeles Air Raid,” as the incident came to be known, left Los Angeles — and the country — shaken.

Despite contradictory explanations for the night’s events – which in turn kicked off more than a half-century of conspiracy theories — the citywide scare demonstrated just how much the world had changed for West Coast Americans after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor just a few months earlier.

Pearl Harbor Buries Itself Into America’s Psyche

Wikimedia CommonsThe attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941.

On Dec. 7, 1941, the U.S. Pacific Fleet in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, was ravaged by a surprise attack from the Japanese air force.

Twenty-one U.S. ships were sunk or damaged. One hundred and eighty-eight American planes were ruined. And 2,403 Americans — including 68 civilians — were killed in less than two hours.

What had up to that morning seemed like far-off ongoing struggles overseas now hit the United States on its home turf. And Los Angeles — a major center for plane and Navy ship manufacturing — feared it would be Japan’s next target.

Within a few days, the U.S. declared war on Japan, Germany, and Italy, and officially entered World War II.

Paranoia was rampant and before long, the U.S. government began to view its own Japanese citizens with suspicion.

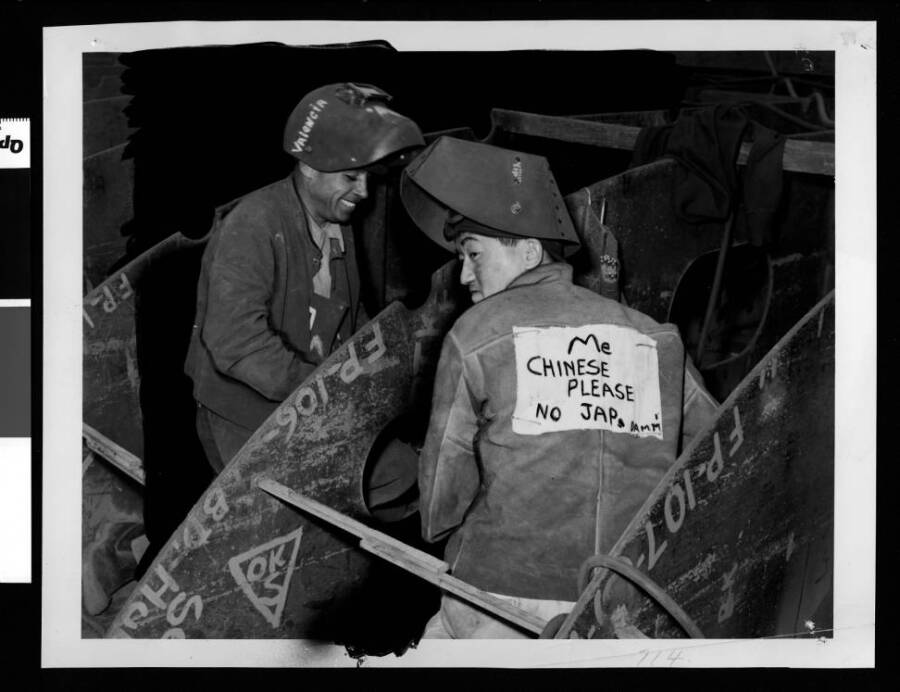

University of Southern CaliforniaLos Angeles worker Howard Yip identifies himself as Chinese to avoid detainment or abuse. January 1942.

On February 19, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed an executive order allowing for the arrest and internment of Japanese Americans.

In Los Angeles, 3,000 first- and second-generation Japanese residents of a fishing village on Terminal Island were the first West Coasters taken into custody.

A few days later, on February 23 — the night before the “Battle of Los Angeles” — a Japanese submarine opened fire on the Ellwood oilfield near Santa Barbara, California.

The oil refinery was already closed for the day and the less than two dozen shells did minimal damage; no one was hurt. Per a declassified military report, “lack of knowledge or more probably, confusion or loss of direction, was responsible for the failure to strike at the Gasoline Plant which would have crippled productions…for some months.”

But in other ways, the attack was a triumph of psychological warfare. The Japanese military had made it clear: California and perhaps all of the West Coast were unsafe and could be targeted for attacks at any time.

The Start Of The Battle Of Los Angeles

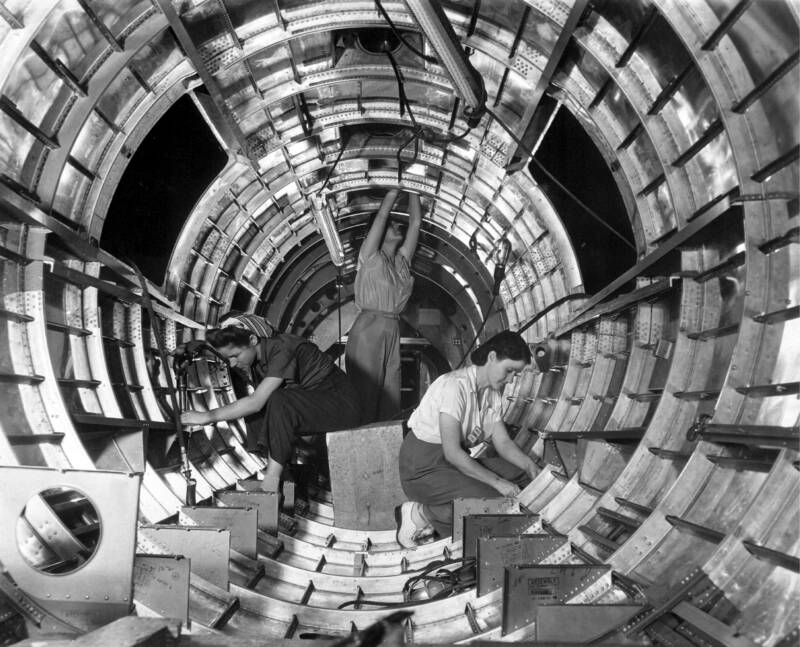

Alfred Palmer/Interim Archives/Getty ImagesWomen workers install fixtures to a B-17F bomber, aka the Flying Fortress, at the Douglas Aircraft Company’s manufacturing plant in Long Beach, California. October 1942.

At 7:18 p.m. on February 24, just 24 hours after the Ellwood attack, a “yellow alert” was called after radar detectors picked up objects more than 100 miles off the coast moving rapidly toward Los Angeles.

At 10:33 p.m. an “all clear” sounded, only for the sirens to declare a full blackout less than four hours later. The battle was on.

Surveying city streets the next morning, Los Angeles reporters documented the damage. Five people were dead. Two had suffered heart attacks during the chaos. Three others, including a police officer, had been killed in car accidents as the explosions overhead distracted frantic drivers.

International News Photos/University of Southern CaliforniaDr. Frank Stewart examining damage done in his kitchen by splinters from an anti-aircraft shell.

In at least three other cases, people’s beds were hit either by fragments or by exploding shells, but they avoided injury because they had gone outside to watch the spectacle unfold. A farmer on Vermont Avenue spent hours rounding up his stampeding herd after one of his cows was killed in an explosion. In Inglewood, a family’s rabbit hutch was destroyed “but caused no serious damage.”

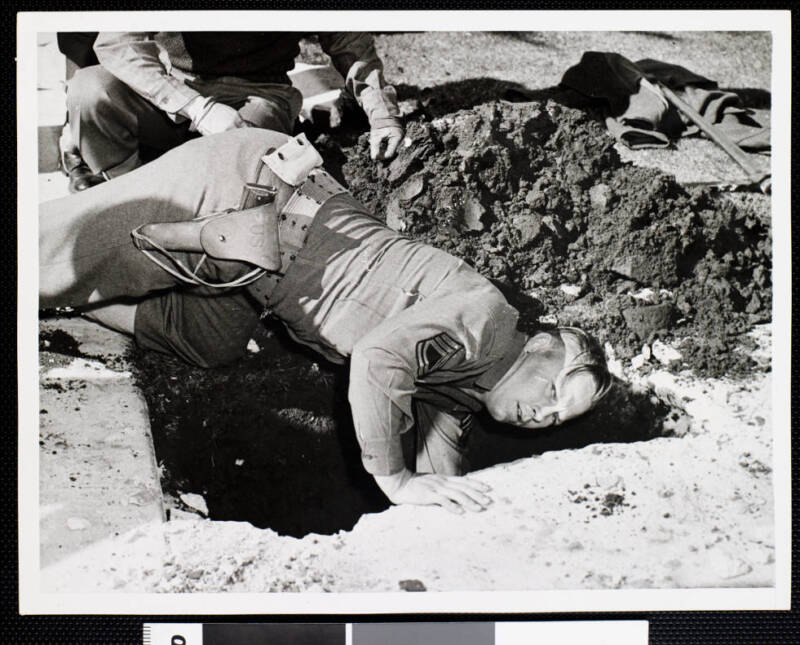

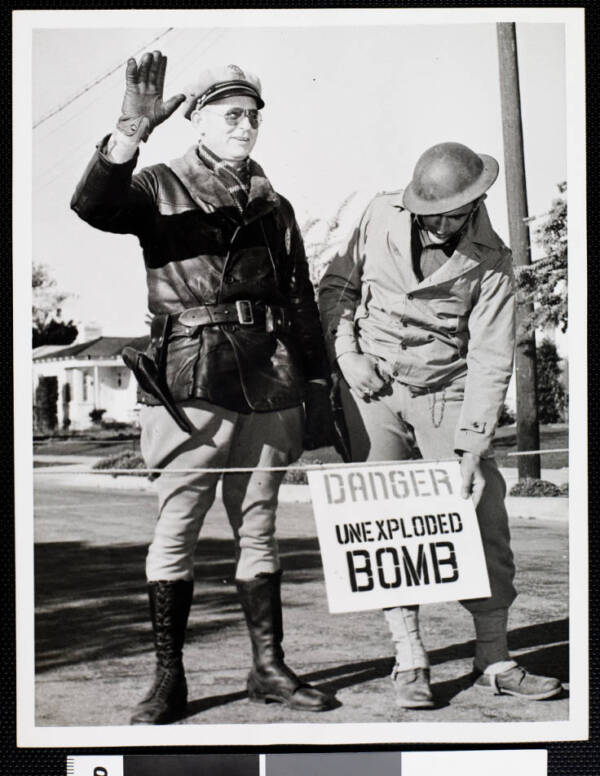

There were also the bombs that had not gone off. One had buried itself inside of a golf course clay bed. Another landed in a Santa Monica resident’s driveway, causing police and soldiers to block off the area with warning signs: “Danger Unexploded Ordinance.”

Looking For Answers In The Aftermath Of The Battle Of Los Angeles

Overnight, Los Angeles had been transformed into a battlefield. That was the terrifying reality of modern warfare. What was additionally disturbing, though, was that there were no signs of any external enemy.

Several Japanese Americans had been arrested and charged with violating the blackout to supposedly send guiding signals to the enemy attackers. But no Japanese planes or other aircraft had been downed in all the hours of firing.

As cleanup continued, it became clear that every bomb that had fallen on Los Angeles had been fired by its own defenses. Although designed to detonate upon reaching a specific altitude, many shells had failed and fallen back to earth.

What did that mean?

According to one conversation recorded in the Los Angeles Times, one witness wondered, “Maybe it’s just a test.” In response, another witness said, “Test, hell! You don’t throw that much material into the air unless you’re fixing on knocking something down.”

International News Photos/University of Southern CaliforniaHomeowner Billie Hall poses on flak-riddled back stoop for a newspaper photographer. Feb. 25, 1942.

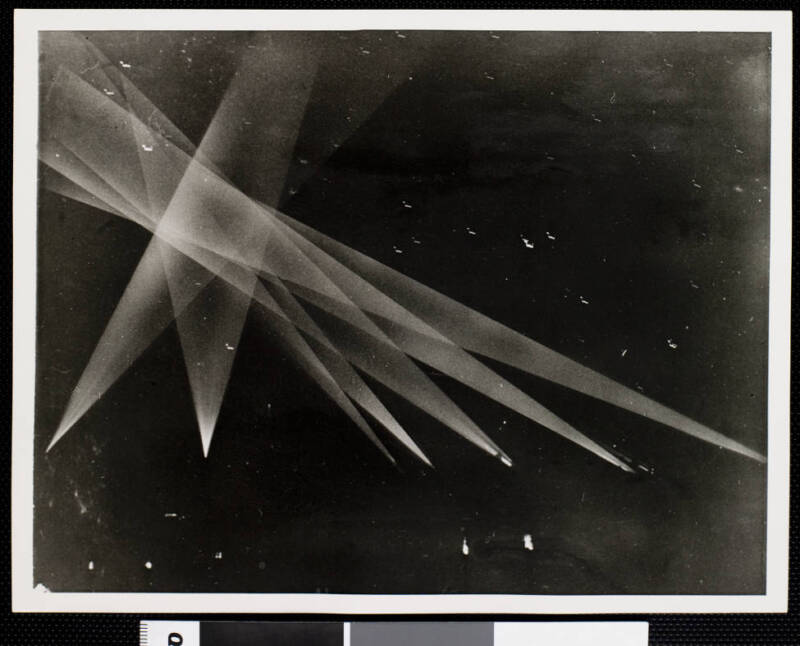

And many witnesses did claim to have seen something. Descriptions of the “object” or “objects” were vague. According to reports, it was slow-moving and most visible when “caught in the center of the lights, like the hub of a bicycle wheel surrounded by gleaming spokes.”

Multiple people had seen “the target inch[ing] along high overhead, flanked by the cherry red bursts,” and others described seeing “one to hundreds” of high-flying planes illuminated by the searchlights and explosions.

Mutually Exclusive Military Explanations

Against the backdrop of this confusion on the ground, the U.S. military’s split response threw open the doors to the controversy and debate that still circles around the Battle of Los Angeles to this day.

From Washington, Navy Secretary Frank Knox announced at a press conference that it was all just a false alarm and that there were no planes over Los Angeles that night.

He blamed the incident on “jittery nerves.” However, the military’s Western Defense Command, the group on the ground in Los Angeles, stated, “The aircraft which caused the blackout in the Los Angeles area for several hours…have not been identified.” The city and the country were perplexed.

The Los Angeles Times published a front-page editorial titled “Information, Please” on February 26:

“More specific public information should be forthcoming from government sources on the subject, if only to clarify their own so-far conflicting statements about it….

Apparently, the Army’s information was that enemy planes were here and preparing for an attack, then or later. Accordingly, it blacked out, started searchlights, opened fire and kept on firing for a long time. Secretary Knox’s information, he says, is that there were no planes at all and that the whole thing was a false alarm….

On this basis, he apparently predicates expression of a belief that such things will make it necessary to remove Pacific Coast war industries inland. The reasoning is at least extraordinary. If there were no planes and no danger, wherein does this particular incident in any way support the theory that our great aircraft industry should be moved inland?”

International News Photos/University of Southern CaliforniaSergeant C.M. Weathers digs out an unexploded anti-aircraft shell in front of the garage of George Watson. To play it safe, in case it was a bomb, the street was roped off and a sign was posted reading, “Danger Unexploded Bomb.”

Confusion Raises More Questions

Adding to the confusion about the “Battle of Los Angeles” were conflicting comments from other military officials. Per another article in the February 26 issue of the Times: “One official source which declined to be quoted directly said American planes quickly went into action. Another said no United States Army planes took off because of the danger from anti-aircraft fire.”

With no clear answers in sight, the local press and sleep-deprived citizens continued to push for an explanation of what they had witnessed. In Washington, President Roosevelt was equally unsatisfied with the report he received from Army Chief of Staff George Marshall that “as many as fifteen planes may have been involved,” some of them possibly commercial, and asked Marshall for clarification.

As is often the case when official explanations fall short, alternative and in some cases “far-out” ones rise to the fore.

The Battle of Los Angeles is no exception. In the intervening decades since the story took over the headlines and then faded away against the onslaught of news from the war front, the incident has become a popular subject for UFO theorists.

Was The Battle Of Los Angeles Caused By A UFO?

The central connecting threads of the prevailing UFO theories are as follows. A mysterious craft appeared over Los Angeles, that in the words of some witnesses resembled a flying saucer. This detail has been enshrined by the sharing of photographs from publications showing what almost resembles a tripod from H.G. Wells’s The War of the Worlds.

According to one “witness” quoted on various conspiracy websites, “The object was huge! It was really enormous! It was practically hovering right over my house… It hardly moved at all. It looked like a lovely pale orange and about the most beautiful thing I have ever seen.”

In the end, the biggest piece of evidence the UFO enthusiasts can point to in this case is that, despite reports of soldiers hitting the target or targets dozens if not hundreds of times, the craft were apparently indestructible. Per another widely quoted anonymous “witness,” “It was like the Fourth of July but so much louder. The military was shooting like crazy on it, but they couldn’t deal any damage.”

Both of these points, of course, only hold weight if one assumes that there was indeed a craft hovering, unmoving in the air and being hit by the artillery. What does the evidence suggest?

Making Sense Of Military Records

Thanks to declassified military reports, we now have insights into what the military was thinking in February 1942. Unfortunately, the information isn’t very comforting.

“At 0243 the Gun Officer reported unidentified planes between Seal Beach and Long Beach; at 306 a balloon carrying a red flare was reported over Santa Monica and firing on it…began at 0307 on orders of the Controller to destroy it. A total of 482 rounds of 3″ were expended at the planes…without visible result except Gun 3E3 reported setting one plane on fire.”

The same report goes on to list the craft appearing over Long Beach, the Douglas Plant, Vermonth Street, and other areas, each time eliciting hundreds of rounds of ammunition fire. In total, the report lists more than 16 military eyewitness testimonies describing everything from weather balloons to 3 to 30 planes flying in a V formation over the city of Los Angeles.

International News Photos/University of Southern CaliforniaSearchlights sweep the skies of Los Angeles. Feb. 25, 1942.

Could These Have Been Japanese Aircraft?

As early as February 26, writers at the Los Angeles Times were speculating about Japanese planes launched from submarines, but the trajectories did not seem to line up with the craft’s speeds and heights described in eyewitness reports.

Years later, in October 1945, more than a month after World War II ended, a communication from U.S. Army General DeWitt stated: “It has been definitely ascertained that the blackout and antiaircraft firing…were caused by the presence of one to five unidentified airplanes. While it is possible these airplanes were launched from Japanese submarines, it is more likely that they were civilian or commercial planes, operated [by] unauthorized pilots.”

Such pilots, if they ever existed, were never found.

Maybe A Japanese Balloon Bomb?

Another strike against Japanese involvement in the Battle of Los Angeles is that no bombs were dropped by enemy craft throughout the incident. While this could have been explained by a reconnaissance operation, the lack of wreckage remains problematic as it is doubtful any single aircraft could have survived the numerous explosions across the night sky.

National Museum of the U.S. NavyA Japanese Fugo balloon bomb found in Bigelow, Kansas. Feb. 23, 1945.

Another alternative explanation for what actually happened in Los Angeles in 1942 might be the Japanese Fugo “Balloon Bomb” project.

During World War II, Japan launched more than 6,000 balloons loaded with incendiary bombs with the intention of setting forest fires across the U.S., stoking panic, and dampening American morale.

The balloon bombs were up to 33 feet in diameter and could carry up to 1,000 pounds of explosives. Per NPR, “When launched — in groups — they are said to have looked like jellyfish floating in the sky.”

While this would seem to explain some of the reports — especially the witnesses who specifically claimed to have seen a balloon — other questions remain. Although Fugo bombs have been found as recently as 2014 and were seen as far inland as Wyoming and Montana, the first reported sighting was in 1944 — two years after the Battle of Los Angeles.

Also, per the reports of the single fatal Fugo encounter which killed a pregnant woman and five children on a hike in Oregon in the spring of 1945, the size and variety of explosives were still identifiable after their detonation.

Even if a balloon bomb had set the Battle of Los Angeles into motion and been destroyed in the process, it’s possible enough of it could have survived to be identified by cleaning crews.

A Weather Balloon?

Another alternative explanation might be that the U.S. military tracked a weather balloon in its radar, not an aircraft or enemy weapon. At the time, anti-aircraft facilities were required to release meteorological balloons every six hours in order to maintain surveillance.

It is entirely possible that the reflections of the flares illuminating the balloons were mistaken for aircraft and, combined with the heightened alert and earlier warnings, someone opened fire and set off a chain reaction.

That, however, was hardly the sort of thing the public wanted to hear.

International News Photos/University of Southern CaliforniaPolice officer and soldier setting up warnings after the “Battle.” Feb. 25, 1942.

As a later declassified report describes the “mutual recrimination” of various authorities, War Secretary Henry Stimson expressed the belief that there were several planes from commercial bases over the city and implied the army was justified in shooting at them, according to the Los Angeles Times.

Meanwhile, the Times maintained that this was “not time for squabbling” and suggested that local army authorities should try to figure out what should be done about the limited space at the air-raid shelters and find out why so many shells failed to explode when it was assumed they were under attack.

But if there were no planes, and no reason for the alarm at all, there was no recasting the events of February 24 and 25 as anything other than a destructive fiasco brought about by “jittery nerves,” just as Secretary Knox said. However, as the Times asked its editorial response on February 26, “Whose nerves, Mr. Knox? The public’s or the Army’s?”

Most Likely Explanation: An Embarrassing, Deadly Military Mistake

Stripped down to the bare facts, the most likely explanation suggests that several servicemen opened fire on a military weather balloon in a fit of panic.

But the smoke from the explosions and the excess of spotlights probably made it seem like there was one enormous craft or countless smaller one — as in the so-called “Spotted UFO” in the infamous Los Angeles Times photograph (which was significantly retouched).

As long as the view was obscured, terrified soldiers and civilians believed the invaders were still there and kept firing for more than four hours until daylight revealed their mistake.

Wikimedia CommonsLos Angeles in 1945.

Even the supposed eyewitness reports describe an object that does not move and is visible only by orange and red lights — the same color as explosions. Upon reflection, there is no evidence to support a theory that anything beyond a weather balloon was there at all.

Faced with the obvious flaws of their prepared defenses, the government and military allowed the story to fade into obscurity out of embarrassment. Soon enough, the “Great Air Raid” faded into obscurity.

When, by the war’s end, it was apparent that the worst impact on the U.S. homeland after Pearl Harbor was a mistake by the American military against one of its own largest cities, no one was eager to illuminate the record.

It wasn’t until 1983, a whopping 41 years after the fact, that the U.S. Office of Air Force History officially reviewed the case and published its own conclusions. In light of the weather balloons and the wartime panic, the “Great Los Angeles Air Raid” was likely nothing other than a mirage sparked by meteorological equipment.

In the end, the answer seems so obvious it can mean only one thing. Thanks to years of embarrassed silence, mystery enthusiasts and UFO conspiracy theorists were gifted the Battle of Los Angeles, just one more fantasy story to come out of Hollywood.

For more weird war stories like the Battle of Los Angeles, learn about the only World War I battle to take place in the United States. Then, read how the United States could have been invaded by the Axis powers in World War II.