Olympe de Gouges demanded the regulation of prostitution and the dissolution of marriage, but when she criticized Maximillien Robespierre's Reign of Terror, he silenced her for good.

In 1791, Olympe de Gouges called for an uprising of French women in her treatise, Declaration of the Rights of Woman. “Women, wake up; the tocsin of reason sounds throughout the universe; recognize your rights.”

During the height of the French Revolution, de Gouges feared that male revolutionaries would ignore women and so she became the most prominent voice calling for her gender’s rights.

De Gouges went too far though when she derided Robespierre’s Revolutionary Tribunal, and her enemies sent her to the guillotine.

Olympe De Gouges, A Teenage Widow

The daughter of a butcher born on May 7, 1748, Marie Gouze reinvented herself after becoming widowed as a teenager.

When her husband died, 16-year-old Gouze changed her name to Olympe de Gouges and moved to Paris on the arm of a wealthy businessman who paid her debts and left her an allowance, vowing never to remarry.

In Paris, de Gouges declared herself an intellectual and dedicated herself to reading the works of Enlightenment philosophers, but she quickly discovered the limits placed on 18th-century women.

Men deemed her illiterate and tried to bar her from writing plays. Yet by the 1780s, de Gouges had nonetheless established herself as a playwright when the Comédie Française staged her works.

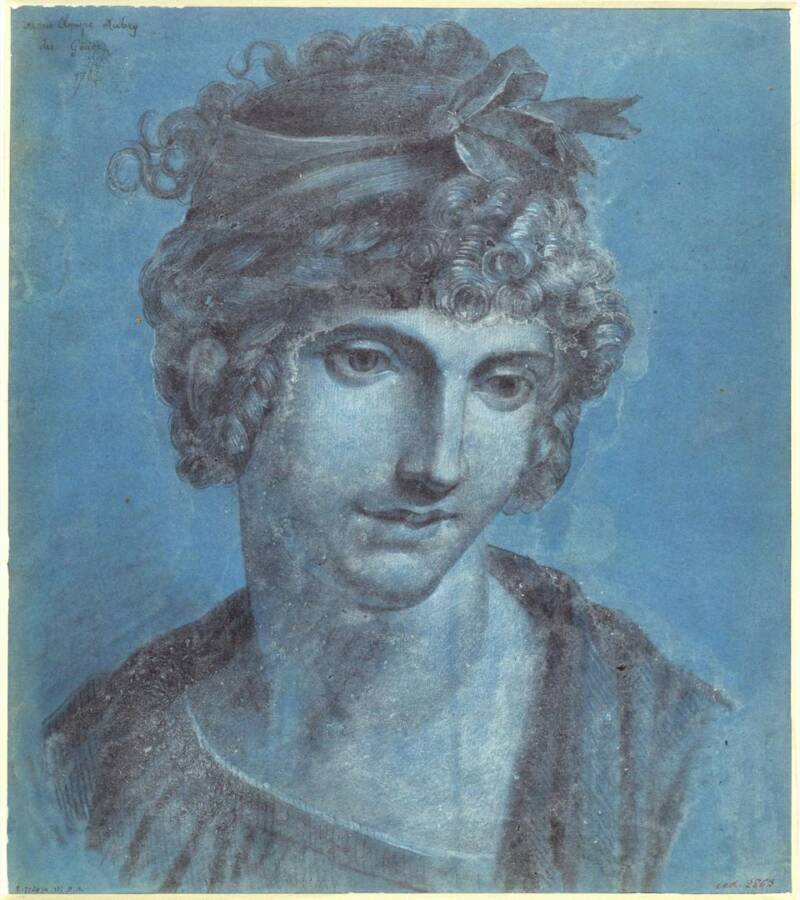

Unknown/Louvre MuseumA watercolor portrait of Olympe de Gouges from 1793.

Even more shocking, de Gouges’s plays focused on political issues. Unlike other women playwrights who published anonymously or wrote plays focused on domestic issues, de Gouges used her writing to highlight injustice.

In her works, de Gouges took controversial positions on the rights of women, divorce, and slavery. She even discussed sexual double standards.

Among her works featuring women as leading characters, de Gouges wrote the first French play criticizing slavery as inhumane. The play was so controversial that riots broke out during one performance and many blamed de Gouges for starting the Haitian revolution.

In response, a male critic declared, “[t]o write a good play, one needs a beard.”

She went on to write 40 plays, two novels, and 70 political pamphlets.

Leading The 18th-Century Fight For Women’s Rights

De Gouges was part of a growing movement that fought for women’s rights. Drawing on the language of the Enlightenment, de Gouges demanded a new approach to a woman’s position in society.

She saw political activism as the key to change and advocated for the rights of unmarried mothers, the regulation of prostitution, and the elimination of the dowry system.

“Man, are you capable of being just? It is a woman who poses the question, you will not deprive her of that right at least. Tell me, what gives you sovereign over empire to oppress my sex? Your strength? Your talents?”

Marriage and divorce appeared frequently in de Gouges’s writings. Based on her own experience, forced into marriage at 16, de Gouges described marriage as a form of exploitation, calling it the “tomb of trust and love.”

The institution of marriage did not garner love, de Gouges argued, but rather subjected women to “perpetual tyranny.” The solution, according to de Gouges, was the right to divorce and civil rights for all women, whether married or unmarried.

Indeed, the young playwright believed women’s rights was a part of the larger battle for human rights.

Fighting In The French Revolution

When the French Revolution broke out in 1789, de Gouges jumped into the fray.

The revolution offered new hope for changing society and attacking injustice. When de Gouges saw how the 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man ignored women completely and the new National Assembly refused to extend citizenship rights to women, she knew the revolution was lacking.

Eugène Delacroix/Louvre MuseumLiberty Leading the People, 1830.

In response to these treatises, de Gouges wrote her most famous work, the Declaration of the Rights of Woman.

Published in 1791, the pamphlet argued that all of the rights French revolutionaries demanded for men should also apply to women. Its first declaration was that: “Woman is born free and remains equal to man in rights.”

The Declaration passionately argued for a woman’s right to own property, women’s representation in government, and rights for unmarried women.

“Women, when will you cease to be blind?” De Gouges wrote. “What advantages have you gathered in the Revolution?”

Considered a radical even before the French Revolution, de Gouges found eventually argued for more moderate, passive positions by 1792. That year, a Revolutionary newspaper wrote:

“Madame de Gouges would like to see a revolution without violence and without bloodshed. Her wish, which proves she has a good heart, is unattainable.”

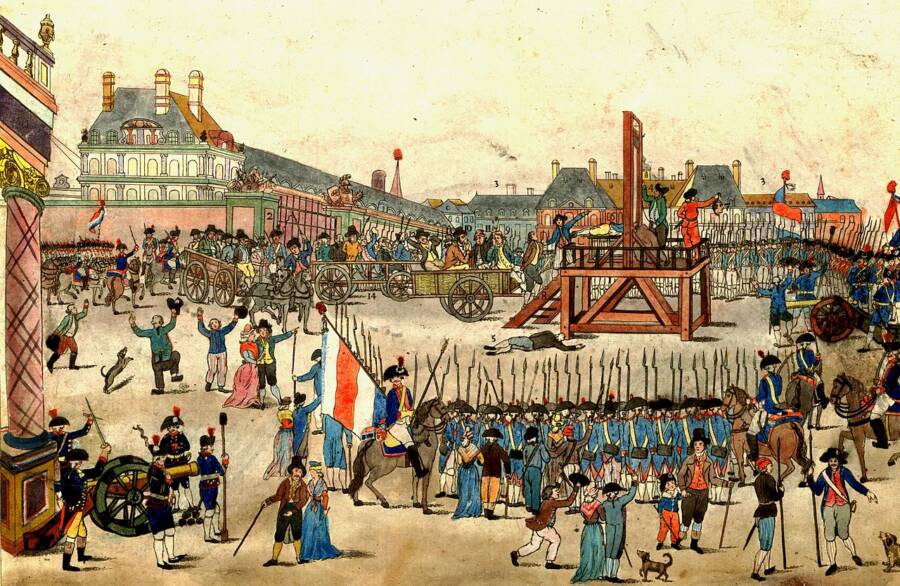

Unknown/Gallica Digital LibraryThe execution of Robespierre in 1794.

During King Louis XVI’s trial, de Gouges argued for the king’s exile rather than his execution. When Maximilien Robespierre rose to power and ushered in the Reign of Terror, de Gouges openly criticized his rule.

A proponent of constitutional monarchy, de Gouges soon found herself labeled an enemy of the Revolution.

Paying With Her Head

The Declaration of the Rights of Woman foreshadowed the end of de Gouges’s life. In one declaration, de Gouges held that “woman has the right to mount the scaffold, so she should have the right equally to mount the rostrum” or the podium from which to espouse her beliefs.

Just two years later, de Gouges faced arrest for these beliefs.

In 1793, de Gouges had called for a direct vote on France’s form of government. She spent the next three months in jail where she continued to publish works defending her political views.

But then on Nov. 2, 1793, the Revolutionary Tribunal convicted de Gouges of printing seditious works after a rushed trial.

The next day, they sent her to the guillotine.

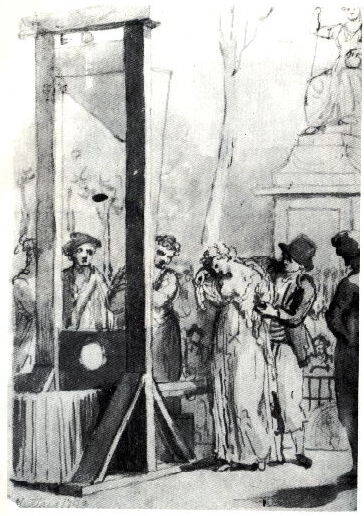

Mettais/Wikimedia CommonsThe execution of Olympe de Gouges by guillotine in 1793.

An anonymous Parisian chronicle captured de Gouges’s final moments:

“Yesterday, a most extraordinary person called Olympe de Gouges who held the imposing title of woman of letters was taken to the scaffold. She approached the scaffold with a calm and serene expression on her face.”

The chronicle summed up her crimes as an attempt “to unmask the [Jacobins],” which was the political group Robespierre endorsed and “they never forgave her, and she paid for her carelessness with her head.”

De Gouges knew the risks of challenging Robespierre’s Revolutionary Tribunal and yet, one month before her arrest, she wrote: “If you need the pure and spotless blood of a few innocent victims to bring forward your days of terrible retribution, add to this great campaign the blood of a woman. I have planned it all, I know that my death is inevitable.”

A Founder Of Modern Feminism

Even decades after her execution, many dismissed de Gouges as an arrogant woman who didn’t know her place.

Weeks after her death, Pierre Chaumette, the prosecutor of Paris, presented de Gouges’s execution as a warning to other women.

She “abandoned the cares of her household to get involved in politics and commit crimes,” Chaumette wrote. “She died on the guillotine for having forgotten the virtues that suit her sex.”

The only woman sentenced to death for sedition during the Reign of Terror, de Gouges’s legacy remained obscure for years. However, today she holds a place as one of the founders of modern feminism.

Unknown/Musée CarnavaletPortrait of Olympe de Gouges, 1784.

In 2016, the French National Assembly honored de Gouges with a statue in her honor.

“At last we have arrived at this moment,” declared Claude Bartolone, president of the assembly. “At last, Olympe de Gouges is entering the National Assembly!”

Olympe de Gouges wasn’t the only feminist who changed history nor was she the most famous woman executed in the French Revolution. Learn about the final days of Marie Antoinette’s life and then check out thesefeminist icons who don’t get enough credit.