On October 16, 1793, Marie Antoinette was beheaded — just months after her husband King Louis XVI met the same fate.

Marie Antoinette: the very name of the doomed queen of France, the last of the Ancien Régime, evokes power and fascination. Against the poverty of late 18th-century France, the five syllables evoke a cloud of pastel-colored indulgence, absurd fashions, and cruel frivolity, like a rococo painting, sprung to life.

The life, and death, of Marie Antoinette is certainly as fascinating. Falling from the Olympus-on-earth of Versailles to the humble cell of the Conciergerie and ultimately the executioner’s scaffold on October 16, 1793, the final days of the last real Queen of France were full of humiliation, degradation, and blood.

This is the story of Marie Antoinette’s beheading at the Place de la Révolution in Paris — and the tumultuous events that led up to it.

Marie Antoinette’s Life At The Conciergerie

Tucked away in its cavernous halls, Marie Antoinette’s life at the Conciergerie couldn’t have been more divorced from her life of luxury in Versailles. Formerly the seat of power for the French monarchy in the Middle Ages, the imposing Gothic palace lorded over the Île de la Cité in the center of Paris as a part administrative center, part prison during the reign of the Bourbons (her husband’s dynasty).

Marie Antoinette’s final 11 weeks before her death were spent in a humble cell at the Conciergerie, much of which she likely spent reflecting on the turns her life — and France — took to bring her from the top of the world to the guillotine’s blade.

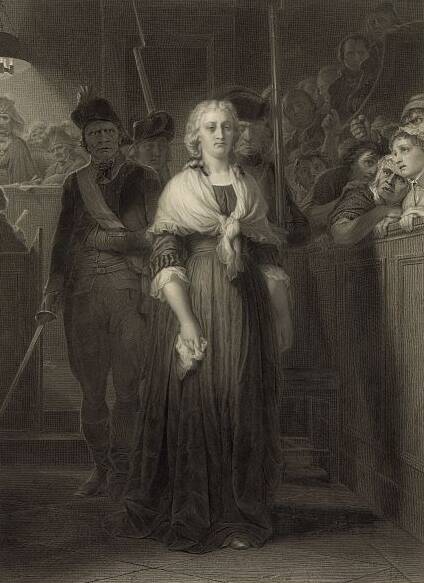

Wikimedia CommonsMarie Antoinette being taken to her death, by William Hamilton.

Marie Antoinette wasn’t even French. Born Maria Antonia in 1755 Vienna to Empress Maria of Austria, the young princess was chosen to marry the dauphin of France, Louis Auguste, when her sister was found an unsuitable match. In preparation to join the more formal French court, a tutor instructed young Maria Antonia, finding her “more intelligent than has been generally supposed,” yet also warned that “She is rather lazy and extremely frivolous, she is hard to teach.”

The Years Before Marie Antoinette’s Death

Marie Antoinette embraced the frivolity that came so naturally to her in a way that stood out even in Versailles. Four years after coming to the heart of French political life, she and her husband became its leaders when they were crowned king and queen in 1774.

She was only 18 and was frustrated by her and her husband’s polar opposite personalities. “My tastes are not the same as the King’s, who is only interested in hunting and his metal-working,” she wrote to a friend in 1775.

Versailles, the former seat of the French monarchy.

Marie Antoinette threw herself into the spirit of the French court — gambling, partying, and purchasing. These indulgences earned her the nickname “Madame Déficit,” while the common people of France suffered through a poor economy.

Yet, while reckless, she was also known for her good heart in personal matters, adopting several less fortunate children. A lady-in-waiting and close friend even recalled: “She was so happy at doing good and hated to miss any opportunity of doing so.”

How The French Revolution Upended The Monarchy

However soft her heart was one-on-one, the underclass of France grew to consider her a scapegoat for all of France’s ills. People called her L’Autrichienne (a play on her Austrian heritage and chienne, the French word for bitch).

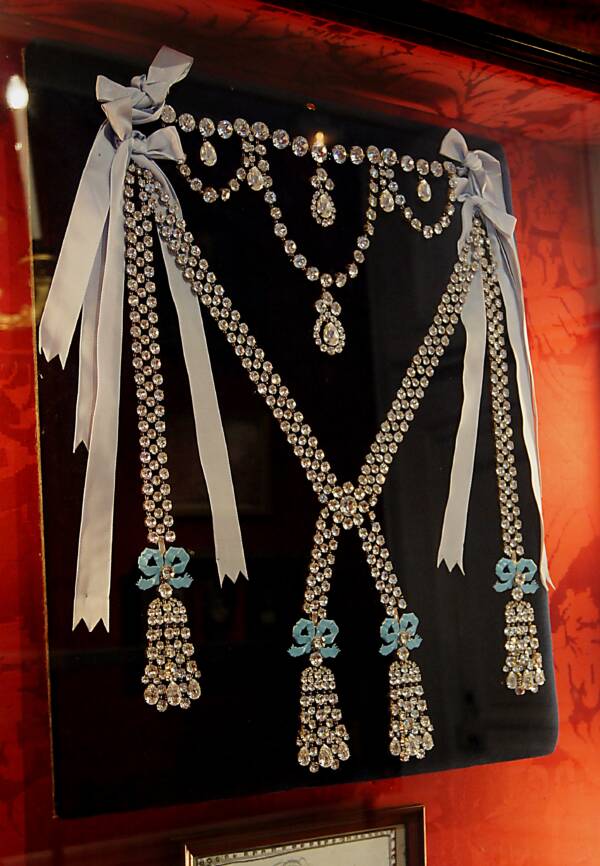

The “diamond necklace affair” made matters even worse, when a self-styled countess fooled a cardinal into purchasing an exorbitantly expensive necklace on the queen’s behalf — even though the queen had previously refused to buy it. When news got out about the debacle in 1785, and people thought Marie Antoinette had tried to get her hands on a 650-diamond necklace without paying for it, her already shaky reputation was ruined.

Wikimedia CommonsA large and expensive necklace with a dark history was a PR disaster for the French monarchy.

Inspired by the American Revolution — and the fact that King Louis XVI put France into an economic depression in part by paying to support the Americans — the French people were itching for a revolt.

Then came the summer of 1789. Parisians stormed the Bastille prison, freeing political prisoners from the symbol of Ancien Régime power. In October of that year, the people rioted over the exorbitant price of bread, marching 12 miles from the capital to the golden gates of Versailles.

Legend has it that a frightened Marie Antoinette charmed the mostly-female mob from her balcony, bowing to them from above. The mob’s threats of violence turned into shouts of “Long live the queen!”

But the queen wasn’t soothed. “They are going to force us to go to Paris, the King and me,” she said, “preceded by the heads of our bodyguards on pikes.”

She was prescient; members of the crowd, carrying pikes topped with the heads of the royal guards, captured the royal family and took them to Tuileries Palace in Paris.

Wikimedia Commons Marie Antoinette faced a revolutionary tribunal in the days preceding her death.

The royal couple wasn’t officially arrested until the disastrous Flight to Varennes in June 1791, in which the royal family’s mad-dash to freedom in the Austria-controlled Netherlands crumbled thanks to poor timing and a too-large (and too-conspicuous) horse-drawn coach.

The royal family was imprisoned in the Temple and on Sept. 21, 1792, the National Assembly officially declared France a republic. It was a precipitous (albeit temporary) end to the French monarchy, which had ruled over Gaul for representing the fall of a nearly a millennium.

The Former French Queen’s Trial And Sentence

In January 1793, King Louis XVI was sentenced to death for conspiring against the state. He was allowed to spend a few short hours with his family until his execution before a crowd of 20,000.

Marie Antoinette, meanwhile, was still in limbo. In early August she was transferred from the Temple to the Conciergerie, known as “the antechamber to the guillotine,” and two months later she was put on trial.

Wikimedia CommonsThe final palace of Marie Antoinette before her death was the Conciergerie prison in Paris.

She was only 37 years old, but her hair had already turned white, and her skin was just as pale. Still, she was subjected to an excruciating 36-hour trial crammed into just two days. Prosecutor Antoine Quentin Fouquier-Tinville aimed to denigrate her character so that any crime she was accused of would seem more plausible.

Thus, the trial began with a bombshell: According to Fouquier-Tinville, her eight-year-old son, Louis Charles, claimed to have had sex with his mother and aunt. (In reality, historians believe he made up the story after his jailer caught him masturbating.)

Marie Antoinette replied that she had “no knowledge” of the charges, and the prosecutor moved on. But minutes later a member of the jury demanded a response to the question.

“If I have not replied it is because Nature itself refuses to answer such a charge laid against a mother,” the former queen said. “I appeal to all mothers here present – is it true?”

Marie Antoinette’s composure in court may have ingratiated her with the audience, but it didn’t save her from death: In the early hours of October 16, 1793, she was found guilty of high treason, depletion of the national treasury, and conspiracy against the security of the state. The first charge alone would have been enough to send her to the guillotine.

Her sentence was inevitable. As historian Antonia Fraser put it, “Marie Antoinette was deliberately targeted in order to bind the French together in a kind of blood bond.”

Inside The Death Of Marie Antoinette

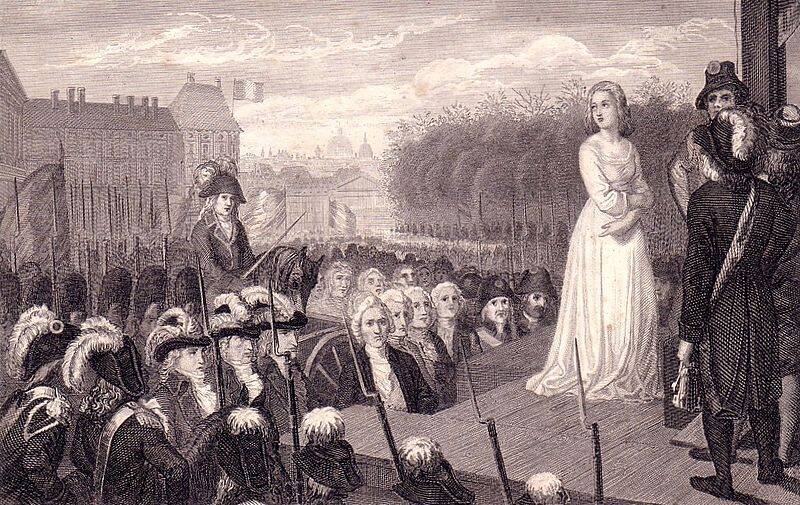

Wikimedia CommonsMarie Antoinette dressed simply for the executioner’s scaffold.

Shortly before she met the guillotine at the Place de la Révolution, most of her snow-white locks were cut off.

At 12:15 p.m., she stepped on the scaffold to greet Charles-Henri Sanson, the notorious executioner who had just beheaded her husband 10 months earlier.

Though the man in the black mask was an early supporter of the Guillotine machine, he probably never dreamed he’d have to employ it on his former employer, the queen of France.

Marie Antoinette, clad in simple white so different from her signature powder-blue silks and satins, accidentally stepped on Sanson’s foot. She whispered to the man:

“Pardon me, sir, I didn’t mean to.”

Those were her last words.

Wikimedia CommonsCharles-Henri Sanson, Marie Antoinette’s executioner.

After the blade fell, Sanson held up her head to the roaring crowd, which shouted “Vive la République!”

Marie Antoinette’s remains were taken to a graveyard behind the Church of Madeleine about half a mile north, but the gravediggers were taking a lunch break. That gave Marie Grosholtz — later known as Madame Tussaud — enough time to make a wax imprint of her face before she was placed in an unmarked grave.

Decades later, in 1815, Louis XVI’s younger brother exhumed Marie Antoinette’s body and gave it a proper burial at the Basilica of Saint-Denis. All that remained of her, besides her bones and some of her white hair, were two garters in mint condition.

After learning about Marie Antoinette’s death, read about Giacomo Casanova’s escape from an inescapable prison or the godfather of sadism: Marquis de Sade.