Angered by the French monarchy's ongoing tyranny, rebels stormed the infamous Bastille prison in Paris, France, on July 14, 1789.

Public DomainA depiction of the storming of the Bastille prison, which marked the beginning of the French Revolution.

By July 1789, the Bastille prison in Paris was a decrepit building that held only seven prisoners. But the royal fortress loomed large in the collective French consciousness, and as rumors of revolution swirled, it became a symbol of the growing frustration with the French monarchy. The storming of the Bastille took place on July 14, 1789, as hundreds of Parisians besieged the prison — and kicked off the French Revolution.

At that point, anger in Paris had reached a pinnacle. After years of supporting the American Revolution, France was teetering on the brink of bankruptcy. Bad harvests, droughts, and rising food prices had stirred up discontent among many French citizens, especially as they were forced to witness the luxurious lives of King Louis XVI and his wife Marie Antoinette.

After years of mounting frustration, the storming of the Bastille on July 14, 1789 marked the first violent step toward a real revolution. The French Revolution would ultimately last about 10 years, during which thousands of people would be executed, including the French king and queen.

It would change France — and the world — forever.

How France Moved Toward Revolution

In the 1770s and 1780s, France supported the American Revolution (in no small part to antagonize its longtime foe, Britain). But by the time the American Revolutionary War ended in 1783, the French were all but bankrupt. Meanwhile, years of bad harvests spread discontent throughout the countryside, and even aristocrats were unhappy to learn of a proposed universal land tax, which they would no longer be exempt from.

Public DomainKing Louis XVI was ultimately executed during the French Revolution.

As discontent simmered across the country, King Louis XVI agreed to take a dramatic step: to convene the Estates General (les états généraux). This assembly of the clergy (First Estate), the nobility (Second Estate), and the commoners (Third Estate), had not convened since 1614. But their historic meeting in May 1789 did little to soothe the national mood.

Tensions developed immediately over how to count votes. If they were counted by status, then the clergy and the nobility would both be part of a powerful two-thirds majority — even though the Third Estate represented the overwhelming majority of the French. If votes were counted by head, however, the Third Estate would have an advantage.

On June 17th, the Third Estate took matters into its own hands and formed the National Assembly. Aware that they represented the majority of the country’s people, they declared that they would proceed without the other two estates if necessary, and Louis XVI reluctantly ordered the clergy and the nobility to join what became the National Constituent Assembly.

Public DomainThe Third Estate vowed to remain united until they had achieved constitutional reform.

But the king wasn’t happy with the National Constituent Assembly, and he quietly began to call in troops around Paris in early July. Rumors soon spread that Louis XVI would forcibly shut the assembly down — or even arrest some of the most outspoken assembly members — and these rumors helped lead to the storming of the Bastille just days later.

The Storming Of The Bastille On July 14, 1789

Art Collection 2/Alamy Stock PhotoThe Bastille once had a fearsome reputation as a political prison, but by the time of the storming, it held just seven prisoners, and there was talk of demolishing it and replacing it with a public square.

By July 1789, the mood in Paris had become incredibly sour. Rumors swirled about an “aristocratic conspiracy” started by the king and his cronies to disband the National Constituent Assembly. The increased presence of troops did not help to ease tensions, and Parisians began to agitate.

After the king dismissed his finance minister, Jacques Necker — who was sympathetic toward the Third Estate — on July 11th, Parisians rose up in protest, pouring into the streets. Some protesters began to amass weapons.

Meanwhile, Bernard-René Jordan de Launay, the Bastille prison’s military governor, began to get nervous. Though his fortress held just seven prisoners — two of whom were mentally ill — the building remained a controversial symbol of royal power, and de Launay worried that the bands of protesters spreading through Paris would soon arrive at his door. Royal authorities sent him 250 barrels of gunpowder, and, by July 12th, de Launay had gathered his men, mostly older or injured veterans, inside the fortress.

Then, on July 14th, the storming of the Bastille began.

Public DomainAn eyewitness painting of the storming of the Bastille by Claude Cholat. Circa 1789.

Driven by rage against the royal regime and by a desire to seize the gunpowder and weapons inside the fortress, as many as 1,000 Parisian revolutionaries and rebellious troops began to gather outside the Bastille, which was long infamous for holding political dissidents who were imprisoned by the king without a trial. After demanding that de Launay give up the gunpowder and other weapons stored at the Bastille — which de Launay refused to do without royal instruction — the crowd began to attack.

Though de Launay attempted to keep the peace by removing the cannons from the Bastille’s walls, the crowd outside the Bastille continued to swell. Both men and women rioted outside the fortress, and two men were able to climb the Bastille’s outer walls and cut the chains that held up one of its drawbridges. As the bridge crashed down, the crowd poured inside, soon engaging in a violent battle with de Launay’s men.

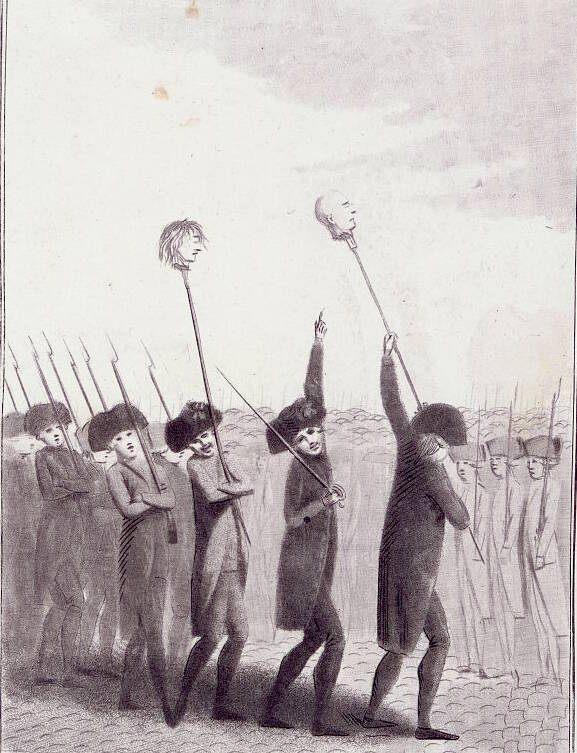

The ever-growing crowd was ultimately able to free the Bastille’s seven prisoners, disarm its guards, and seize its stores of gunpowder (though, in a desperate moment, de Launay had considered detonating all the gunpowder and the crowd along with it). Eight of the men guarding the Bastille were lynched by the crowd, and after de Launay officially surrendered, a mob of revolutionaries marched him through the streets of Paris, beat him, spat on him, and debated the most brutal ways they could execute him.

Finally, de Launay shouted, “Just let me die!” and kicked one of his captors in the groin, leading him to be hit with a sudden onslaught of daggers, bayonets, and pistol shots near the Hôtel de Ville.

The crowd then cut off his head and stuck it on a pike.

Public DomainThe crowd murdered Bernard-René Jordan de Launay and Jacques de Flesselles, who held a position roughly equivalent to the mayor of Paris, and stuck their heads on pikes.

Following the storming of the Bastille, King Louis XVI purportedly demanded to know if it had been a revolt. The Duke of La Rochefoucauld responded: “No, sire, it is a revolution.” Indeed, though the king attempted to appease the crowd by reinstating Necker and withdrawing troops from Paris, he could not stop the rising tide of rage. The French Revolution had begun.

The Impact Of The Storming Of The Bastille

Though nearly 100 insurgents died during the storming of the Bastille, the military governor had surrendered to the surviving revolutionaries in a matter of hours, cementing a historic win for their cause. The capture of the Bastille — which was demolished soon after the conflict — provided the rebels with momentum like they never had before. It was their chance to bring the old regime to an end and put something new in its place.

Indeed, the storming of the Bastille is generally thought to mark the start of the French Revolution, which would endure for the next 10 years. During that time, much of the revolutionaries’ anger was directed toward King Louis XVI and his glamorous wife Marie Antoinette — though she likely never dismissed their concerns by quipping, “Let them eat cake.”

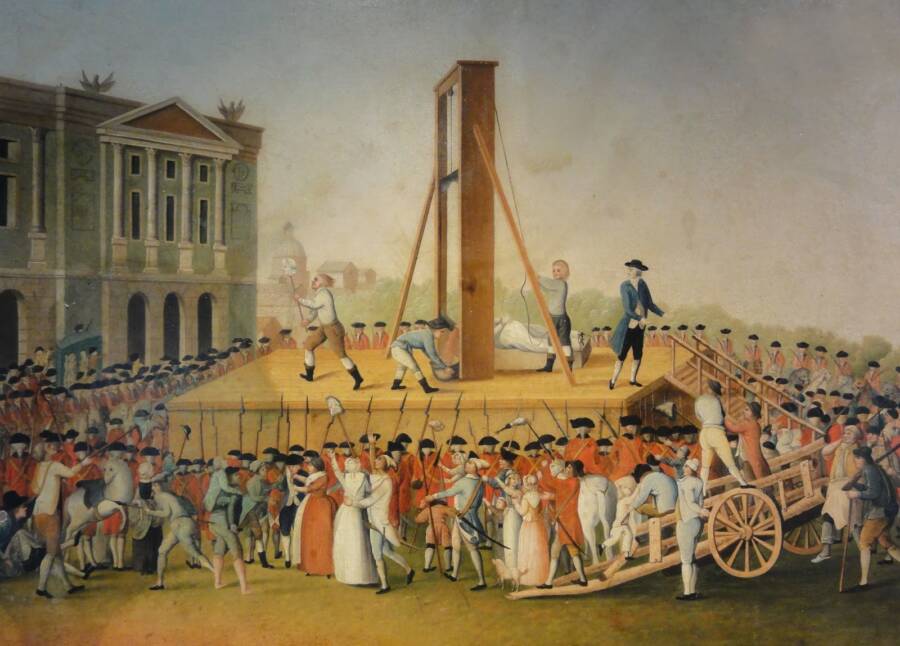

In 1792, the king, queen, and their children were imprisoned. The king was guillotined on Jan. 21, 1793 by royal executioner Charles-Henri Sanson, and Marie Antoinette was guillotined on Oct. 16, 1793 by Sanson’s son.

Public DomainA depiction of Marie Antoinette’s execution, with her severed head being shown to the crowd.

The French Revolution would also claim the lives of thousands of other people, some of whom died at the guillotine. The bloody revolt would not come to an end until 1799, when Napoleon Bonaparte seized power.

It was a cataclysmic period in world history, one that would tear down the French monarchy, usher in the rise of Napoleon, and transform the balance of power in Europe. And it all began with the storming of the Bastille.

As such, July 14th, “Bastille Day,” is marked as a national holiday in France, and celebrated in a way that’s similar to the Fourth of July in the U.S. Though de Launay chose not to light up the Parisian skies with gunpowder back in 1789, the French annually set off fireworks on July 14th each year.

After all, the storming of the Bastille did not just change the course of French history. It also transformed the world in dramatic and profound ways.

After reading about the storming of the Bastille, learn about the Drownings at Nantes, a horrific crime against humanity that took place during the French Revolution. Then, read about Charlotte Corday, the woman who brutally assassinated a French revolutionary hero.