From March 18 to May 28, 1871, a revolutionary government that called itself the Paris Commune controlled the French capital — and changed the country forever.

Moloch/Musée CarnavaletA 19th-century illustration of women defending the barricades of the Paris Commune.

For 72 short days in 1871, workers controlled the city of Paris.

After the devastation of the Franco-Prussian War, Parisian workers were fed up with their country’s government. So they united against their leaders, briefly drove officials out of the city, and created their own government that would live on in socialist imaginations for decades: the Paris Commune.

This is the true story of the social revolution that only had two months to fulfill its promises — and the bloody aftermath of the insurrection.

From War To Workers’ Revolt

The road to the Paris Commune began on July 19, 1870, when French Emperor Napoleon III declared war on Prussia. At the time, he was eager to reclaim France’s status as a leading imperial power in Europe.

But the emperor soon failed in those ambitions, as Prussia’s clear military superiority quickly allowed it to overpower the French troops.

After Napoleon III surrendered to the Prussians at the Battle of Sedan — and allowed himself to be taken prisoner — the French erupted in anger. They revolted against the Second Empire, and so the Third Republic was then established. But the new government did not please many Parisians.

According to History, the Third Republic struck many Parisian workers as too conservative and too similar to the country’s former monarchy. Members of the local National Guard in Paris were especially skeptical.

In early 1871, as the Third Republic government officials tried to establish a peaceful relationship with the Prussians and restore order in the French capital, they made the fateful decision to disarm the Parisian National Guard.

Musée CarnavaletThe National Guard’s cannons at the neighborhood of Montmartre, which the French government wanted to remove.

On March 18, 1871, the French government under the newly elected leader, Adolphe Thiers, dispatched troops from Versailles to remove the National Guard’s cannons from the Montmartre neighborhood of Paris.

As the feminist writer André Léo observed, the artillery was “turned toward the centre of the city, toward the city of luxury and palaces, of monarchical plots, of infamous speculators, and of cowardly governments.”

And they would remain that way. Local citizens, many of them women, interposed themselves between the troops and the cannons. Though the generals ordered their troops to shoot into the crowd, many of the soldiers refused to follow these commands. Eventually, two generals were killed by National Guardsmen and deserting government troops.

When Thiers found out, he ordered his loyal troops and government officials to retreat from Paris and return to Versailles, where they could plan an attack. Parisians would respond by electing a new government days later.

The Paris Commune In Action

Shortly after the Third Republic officials left the French capital, Parisian workers, National Guardsmen, and other citizens quickly came together to create the revolutionary Paris Commune. On March 26th, the central committee of the guard organized elections for new “Communard” officials who would run the city, operating from the famous Hôtel de Ville.

Then, the government vowed to enact a revolutionary program.

“You have just given yourselves institutions that defy these attacks,” the Communard leaders proclaimed to the citizenry. “You are masters of your destiny. Strong in your support, the representatives that you have just established will repair the disasters caused by the fallen powers.”

And the Paris Commune began to fulfill its promises rather quickly.

The newly formed government passed several decrees, ordering a strict separation of church and state, abolishing conscription, ending the practice of night work, establishing child labor laws, and offering pensions to family members of National Guardsmen who had died while in service.

As part of a campaign to erase religion from public life, it also switched to the French Republican calendar, adopted in the earlier French Revolution.

André Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri/Wikimedia CommonsA statue of Napoleon Bonaparte, toppled by Communards during the insurrection.

Though women weren’t members of Communard leadership and they weren’t allowed to vote, they still participated heartily in the revolution.

“Communard women, with the support of some Communard men, transgressed gendered barriers to labour, politics, religion, education, and the battlefield,” historian Carolyn Eichner wrote for Aeon. Some women even boldly proposed feminist policies like equal pay and the right to divorce.

Meanwhile, other citizens worked to militarize Paris, erecting barricades made of cobblestones and debris to block roads. National Guardsmen prepared for an imminent attack from French government troops.

But according to Britannica, supporters of the Paris Commune struggled to organize themselves militarily and left some sections of the city undefended.

And as troops readied to attack Paris from the outside, some of the Communards seemed more interested in destroying monuments on the inside — especially those that glorified the French military or monarchy.

One of the most memorable acts of destruction was the toppling of the Vendôme Column, a monument that honored Napoleon Bonaparte. Declaring the column a “monument to barbarism, a symbol of brute force and glory, an affirmation of militarism, a negation of international law,” the Paris Commune tore down the column on May 16th.

It would be one of the last things the Commune would do.

Inside The Fall Of The Paris Commune

Semaine Sanglante (Bloody Week) marked the violent end of the Commune.

By late May, Thiers and other French government officials were prepared to take back Paris. Not only had they organized tens of thousands of loyal troops, but earlier that month, France had signed an official peace treaty with Prussia, meaning it could focus its full attention on the Commune.

On May 21st, French government troops found a noticeable gap in the Commune’s defenses and began pouring into Paris.

Given the Paris Commune’s poor leadership, fractured forces, and general lack of planning, Thiers’ forces easily rampaged through the city — quite literally — shooting and killing countless Communards in their path.

At the same time, the Communards burned much of the city and continued destroying vestiges of the monarchy, such as the famed Tuileries Palace.

But the Commune was on its last legs.

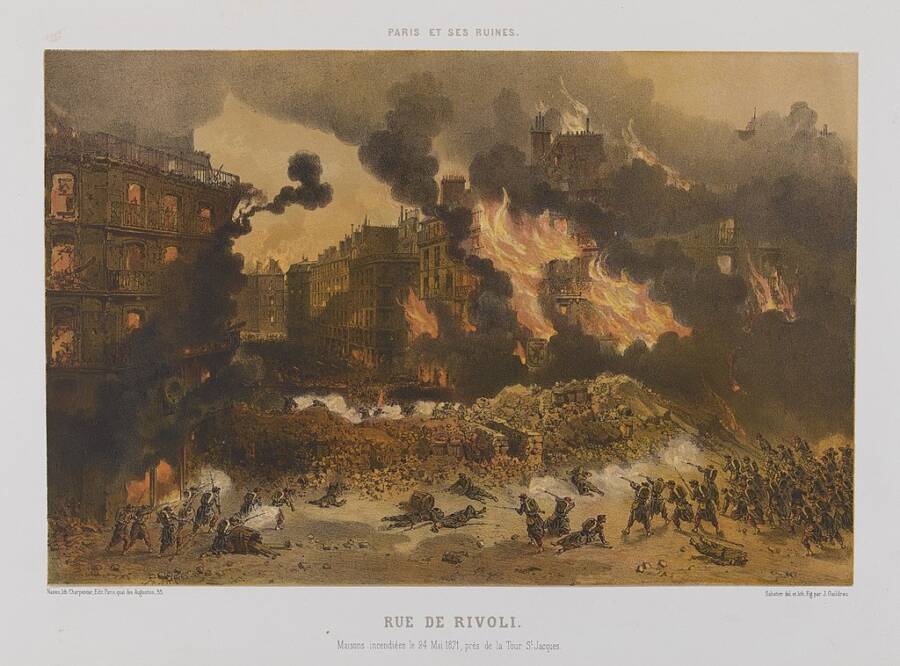

Léon Sabatier/Wikimedia CommonsA lithograph of the Rue de Rivoli in Paris burning during “Bloody Week.”

Still, the Communard newspaper Le Salut Public urged Parisian workers, National Guardsmen, and other citizens to keep fighting in its last issue.

“Gather yourselves around the red flag on the barricades, around the Committee of Public Safety — it will not abandon you,” its editor, Gustave Maroteau, wrote. “We will not abandon you, either. We will fight with you until the last cartridge, behind the last paving stone.”

But it was all in vain. By May 28th, the French government troops had retaken the city, and the Paris Commune would be no more.

In the aftermath, about 20,000 people who had participated in the insurrection were killed, 38,000 of them were arrested, and over 7,000 were deported. And much of the city itself lay in ruins.

“Jumbled together are victors and vanquished,” one surviving Communard, Maxime Vuillaume, recorded in his diary. “Executioners and the executed. Surrounded fighters lie dead on the paving stones.”

The Legacy Of The Paris Commune

Shortly after the Paris Commune’s violent fall, Communist philosopher Karl Marx gave an address about the revolutionary government, saying that class struggle “cannot be stamped out by any amount of carnage. To stamp it out, the governments would have to stamp out the despotism of capital over labor — the condition of their own parasitical existence.”

Marx continued, “Working men’s Paris, with its Commune, will be forever celebrated as the glorious harbinger of a new society.”

Today, some parts of the Paris Commune are indeed celebrated. After all, many of the policies passed by the government are still found in many modern-day democracies, especially those related to workers’ rights and the separation of church and state. The Commune has also been described as one of the key events that helped shape modern France.

Hippolyte-Auguste Collard/Metropolitan Museum of ArtAn 1871 photograph of Paris’ City Hall after the devastation of the Commune.

But not everyone reflects on the Commune with fondness. Some denounce the Commune for its violence against political opponents — especially Catholic officials — and its destruction of countless historical monuments.

And so its legacy remains controversial, with politicians and intellectuals still debating about it more than 150 years after its rapid rise and fall.

As one British historian of France, Robert Tombs, put it:

“Here was a revolutionary movement that didn’t succeed, that didn’t last that long. And therefore people are free to project onto it all sorts of things that might have happened and would have been good. So it’s become an icon of feminism, secularism, of popular democracy. What it would actually have turned out as had it succeeded, we will never know.”

After reading about the Paris Commune, check out 40 historical photos from America’s battle for fair working conditions. Then, learn about the Haymarket Riot, a workers’ rebellion that took place in Chicago.