The Peshtigo Fire of 1871 killed up to 2,500 people, yet it was largely overshadowed by the more famous Great Chicago Fire, which occurred on the same night.

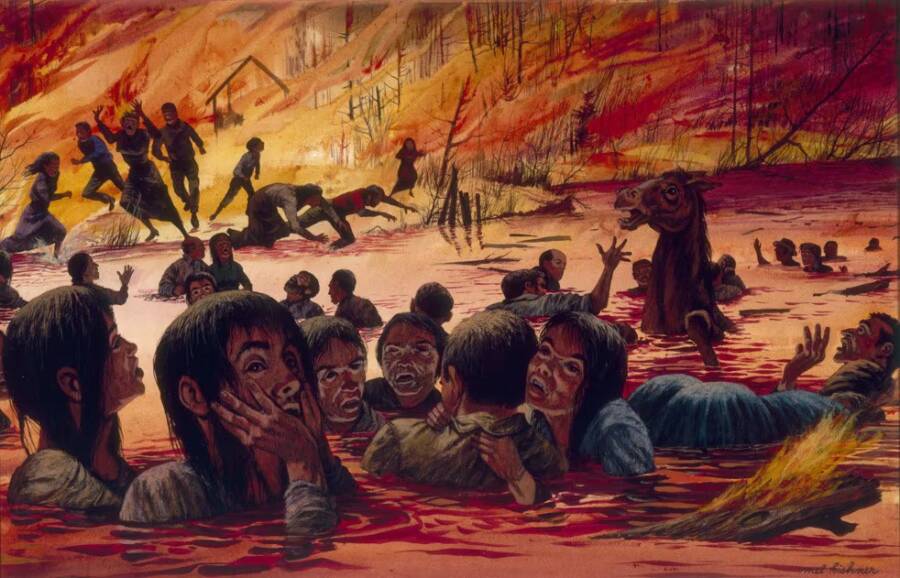

Wisconsin Historical SocietyA painting of the Peshtigo Fire by Mel Kishner.

On October 8, 1871, the Great Chicago Fire tore through the city, killing 300 people and destroying some 17,000 wooden structures. It’s remembered today as one of the most infamous fires in American history, and most people know the story about Mrs. O’Leary cow’s allegedly starting the blaze by kicking over a lantern. But on the very same night, a far more deadly fire occurred some 250 miles north of Chicago: the Peshtigo Fire.

The deadliest fire in American history, the Peshtigo Fire in Peshtigo, Wisconsin, killed as many as 2,500 people in a single night. The entire town of Peshtigo went up in flames, and the devastation was so great that some have since speculated that the town was hit by a fiery comet.

Yet while the Great Chicago Fire became an important chapter in American history, the Peshtigo Fire has been all but forgotten. This is what happened on the terrible night in Wisconsin back in 1871.

The Town That Turned Into A Tinderbox

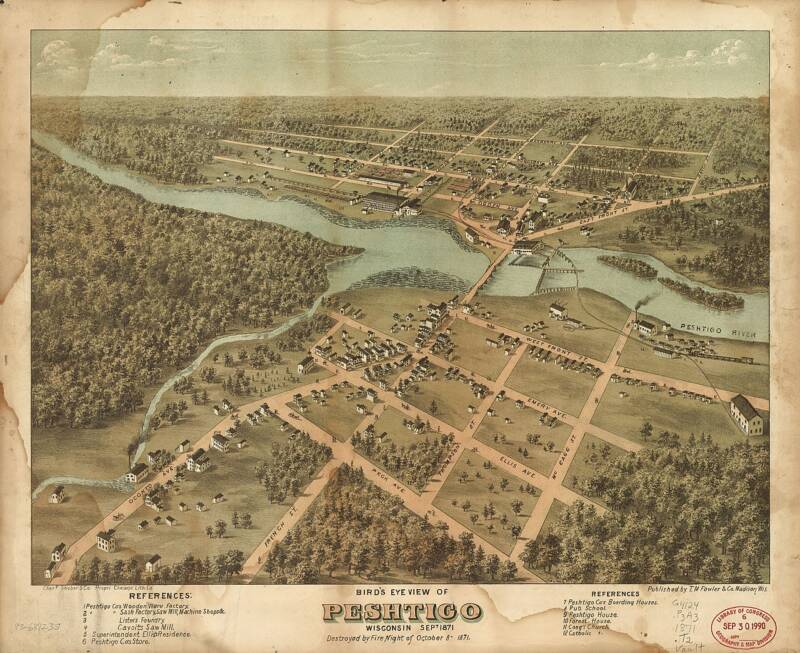

Three decades before the Peshtigo Fire, the town of Peshtigo, Wisconsin was settled along the banks of the Peshtigo River. In 1838, the town’s first sawmill was built, and Peshtigo quickly became an important mill town in the region. It sent its abundant white pines down the river and through Lake Michigan, where timber from Peshtigo was consumed across the Midwest.

Public DomainA bird’s eye view of Peshtigo, Wisconsin, in 1871, created just one month before the Peshtigo Fire.

Unfortunately, Peshtigo’s industrial success made it vulnerable to fire.

Not only was the entire town made of wood — both its sidewalks and structures were wooden, and even the roads were paved with wood chips — but its lumber industry created the perfect conditions for an inferno. As Minnesota Public Radio pointed out in 2002, lumberjacks left huge mounds of branches out in the woods, and millers left behind piles of wooden slabs and sawdusts. Meanwhile, burning was a popular way of clearing land in the region, used by both farmers and railroad builders alike.

Though the summer of 1871 was one of the driest on record, people in and around Peshtigo continued to use fire as a tool. Minnesota Public Radio reports that the air was so thick with smoke in the week before the fire that harbormasters in nearby Lake Michigan had to use their foghorns to keep ships from running aground. Meanwhile, a 1921 retrospective on the Peshtigo Fire in the Peshtigo Times recalls that there were at least two large fires in Peshtigo before the Peshtigo Fire, one of which destroyed a house and barn.

Peshtigo Fire MuseumA scene from Peshtigo’s thriving 19th-century lumber industry.

Yet none of this was a matter of serious concern in Peshtigo. That is, until the winds started to pick up on October 8, 1871.

The Peshtigo Fire Of October 1871

Wisconsin Historical SocietyA painting by Mel Kishner of townsfolk during the Peshtigo Fire.

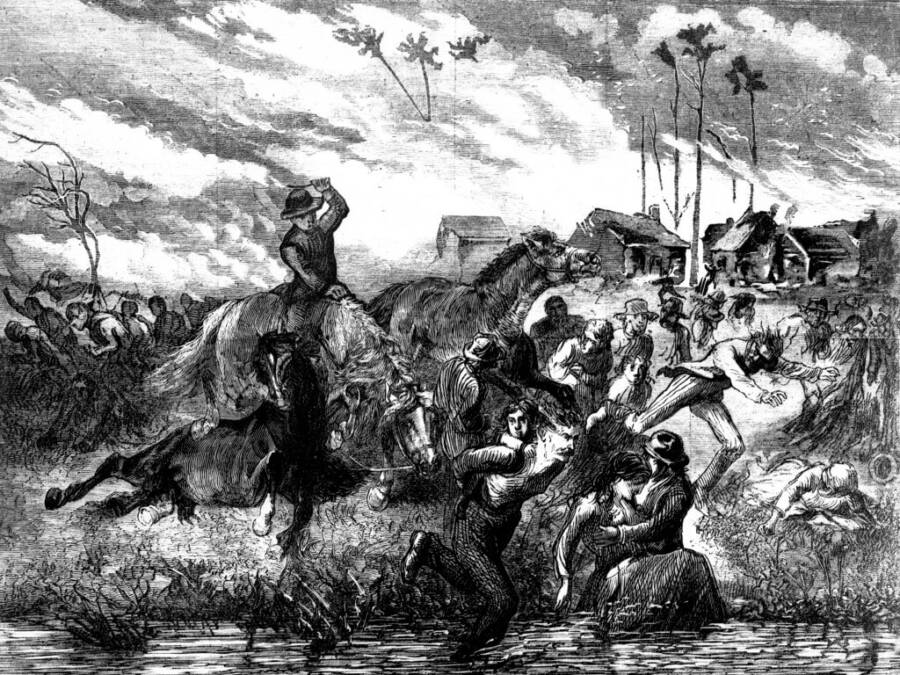

On the day of the Peshtigo Fire, a powerful cold front came sweeping through the Midwest. It brought with it intense winds, which fanned smoldering fires into blazes. And by 10 p.m. that night, Peshtigo’s citizens began to hear the sound of a rumble — that began to grow into a roar.

“On looking towards the west, whence the wind had persistently blown for hours past, I perceived above the dense cloud of smoke over-hanging the earth, a vivid red reflection of immense extent, and then suddenly struck on my ear, strangely audible in the preternatural silence reigning around, a distant roaring, yet muffled sound, announcing that the elements were in commotion somewhere,” Reverend Peter Pernin, a witness, later recalled.

“The roaring,” he continued, “sound like thunder seemed almost upon us.”

Then, in what seemed like the blink of an eye, fire descended on the town. Small fires in the region exploded into a firestorm, which, powered by 100-mile-per-hour winds, swept across Peshtigo. Buildings burned in an instant as the high winds knocked people of their feet, and the hot, dry air made it almost impossible to breath. Meanwhile, the temperature spiked up to 2,000 degrees, and a vortex created by the wind sucked the smoke up into the sky, so that the flame-filled air became agonizingly clear.

Those lucky enough to escape the blaze made their way to the river. But even there, they weren’t safe from the fire which had consumed their town.

Peshtigo Fire MuseumA depiction of people running into the Peshtigo River during the Peshtigo Fire.

“Once in water up to our necks, I thought we would, at least be safe from fire, but it was not so,” Pernin later recalled.

“[T]he flames darted over the river as they did over land, the air was full of them, or rather the air itself was on fire. Our heads were in continual danger. It was only by throwing water constantly over them and our faces, and beating the river with our hands that we kept the flames at bay… as far as the eye could reach into space… I saw nothing but immense volumes of flames covering the firmament, rolling one over the other with stormy violence as we see masses of clouds driven wildly hither and thither by the fierce power of the tempest.”

The next morning, those who managed to survive through the night found that the town was gone. The Peshtigo Fire had destroyed everything.

‘The Night America Burned’: The Aftermath Of The Peshtigo Fire

Of the 2,000 people living in Peshtigo, between 500 and 800 had lost their lives in the Peshtigo Fire. But the blaze had extended far past the town — it had consumed an astounding 1.2 million acres — and hundreds of people in the surrounding communities had perished as well. It’s believed that up to 2,500 people died in all, making it the deadliest fire in American history.

Wisconsin Historical SocietyBurned out streets following the Peshtigo Fire in October 1871.

But it was not the only fire to occur that night.

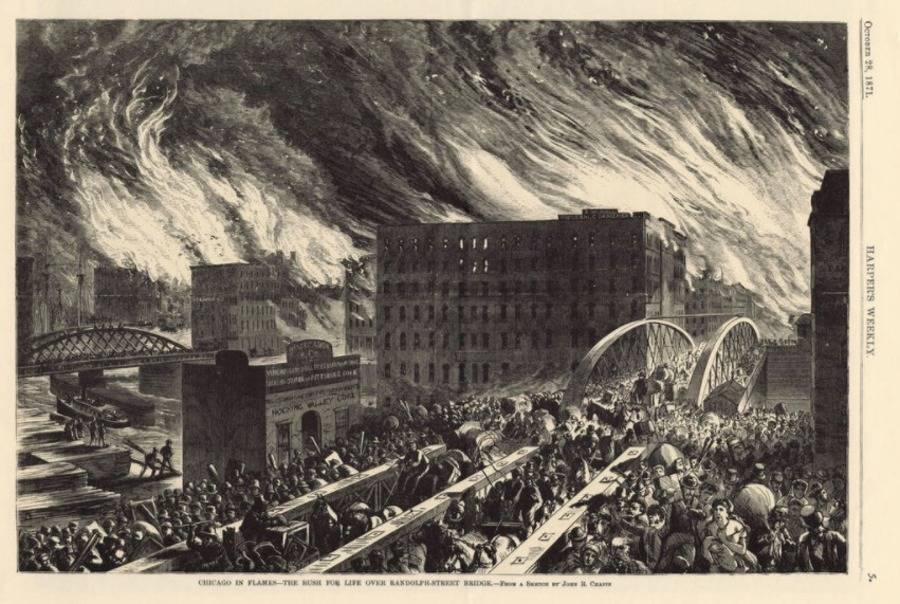

Not only had fires struck that night in Holland, Port Huron, and Manistee, Michigan, but a blaze had also erupted hundreds of miles south of Peshtigo in Chicago. Though not really started by a cow, as popularly claimed, the Great Chicago Fire was immensely destructive, and killed some 300 people and destroyed 17,000 structures as it burned through the metropolis.

The Great Chicago Fire was terrible — but death toll in the Peshtigo Fire was far worse. Why then, was one remembered and not the other?

Perhaps the destruction of a city seemed more newsworthy than the destruction of a town of just 2,000. But perhaps it had something to do with telegraph lines. In Peshtigo, the town’s only telegraph line was destroyed by the blaze, meaning that news of the fire didn’t reach newspapers or government officials until much later. Meanwhile, news of the Great Chicago Fire spread far more easily and quickly across the nation.

Public DomainA depiction of the Great Chicago Fire which, while not as deadly as the Peshtigo Fire, became the more famous of the two blazes.

Though the Peshtigo Fire never became as well known as the Great Chicago Fire, it stands as the deadliest fire in American history. It was so hellishly terrible that some believe that it was caused by fragments of Comet Biela — though this theory has never been proven.

Rather, it seems that the Peshtigo Fire was triggered by terrestrial causes. The lumber industry had left Peshtigo vulnerable to fire, and the town itself was more or less made of wood. This, combined with the use of fire to clear land, the dry conditions, and the high wind, turned Peshtigo into a tinderbox.

That’s why the night of Oct. 8, 1871, during which fire consumed Peshtigo, Chicago, and other places, is sometimes called “the night America burned.”

After reading about the Peshtigo Fire of 1871, the deadliest fire in U.S. history, discover the tragic story of the Iroquois Theater Fire, the devastating 1903 blaze that killed 600 people and transformed building safety standards in the United States. Or, learn about the devastating Happy Land Fire, the worst arson attack in New York City history that killed 87 people.