After the Pilgrims arrived in Massachusetts, the local Indigenous population fell from 30,000 to just 300 — within a decade.

Library of CongressA depiction of the “first” Thanksgiving in 1621 — as disease had already ravaged the land.

While exact figures remain debated, historians estimate that 18 million Indigenous people inhabited the North American continent before the 16th century. But within years of European settlers arriving, these populations would be decimated by up to 90 percent, killed by diseases that colonists brought with them to the New World.

And when the Mayflower arrived at Plymouth, Massachusetts, in 1620, the 102 Pilgrims aboard found nothing but empty villages. Tools were left behind in unoccupied houses, and skeletal remains littered the landscape. The reason was a glaring pestilence, which the Pilgrims deemed an act of God preparing the land for their arrival.

“Within these late years, there hath, by God’s visitation, reigned a wonderful plague, the utter destruction, devastation, and depopulation of that whole territory, so as there is not left any that do claim or challenge any kind of interest therein,” decreed the 1620 Charter of New England by King James I.

Previous colonists had indeed brought fatal Old World diseases to the New World, including smallpox, chickenpox, syphilis, malaria, influenza, measles, and the bubonic plague. But in Massachusetts, it was a unique disease called leptospirosis that killed nine out of 10 native Wampanoag. And after the Pilgrims landed, another 90 percent would die within the decade.

Old Diseases And The New World

Wikimedia Commons“Landing of Columbus” (1847) by John Vanderlyn.

Christopher Columbus arrived on the Caribbean island of Hispaniola in 1492. Within 25 years, the Indigenous population of 250,000 plummeted by 95 percent to fewer than 14,000. Native immune systems were unable to thwart Old World diseases. Death rates were higher than during the Black Plague in Medieval Europe.

While Indigenous people on the North American mainland would endure similar suffering, the eastern seaboard appeared to hold thriving communities until the early 1600s. When French explorer Samuel de Champlain sailed by Patuxet (later renamed Plymouth) in 1605 he described “a great many cabins and gardens.” He even drew a map of thriving villages surrounded by cornfields.

By that point, it’s believed the Wampanoag tribe had lived on the land for 10,000 years and had a population of 12,000. Even when Captain John Smith arrived in Massachusetts Bay in 1614, he described regional tribes as inhabiting “the Paradise of all those parts.” Within a couple of years, however, things took a turn.

In 1616, English explorer Captain Richard Vines noted that local populations on the coast of Maine “were sorely afflicted with the Plague, for that the Country was in a manner left void of inhabitants.” These afflictions would skyrocket between 1616 and 1619. The survival rate is estimated to have been just 10 percent.

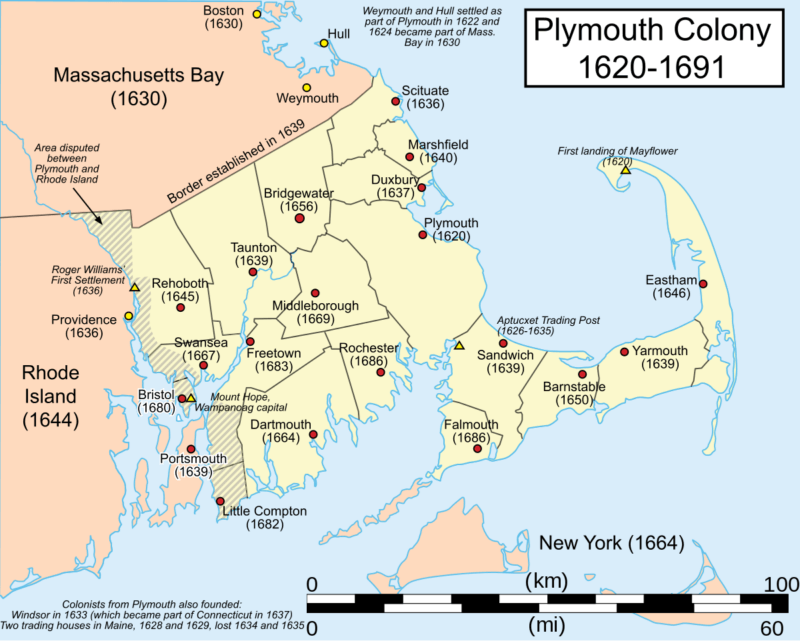

Wikimedia CommonsA map of Plymouth Colony’s settlements from 1620 to 1691.

Then the plague spread south. The peak of the epidemic in 1618 saw thousands of Wampanoag wiped out along the Massachusetts Bay shoreline. The highest rate of infection befell Boston Harbor and Plymouth Bay, with ancient plantations left empty. While the Wampanoag described it as “The Great Dying,” Europeans called it the “Indian fever.”

Both the Indigenous Americans and Europeans were baffled by the mysterious plague, which traveled along the coastal trade routes of the Abenaki tribe. Early colonial merchant Thomas Morton would later describe the grim scene as a new Golgotha, the site of Jesus’ crucifixion.

Only recently has the precise cause come to light.

The Pilgrim Plague Of Leptospirosis

Among the first Wampanoag man to greet Pilgrims in 1620 was Tisquantum, whom settlers called Squanto. He had been abducted in 1614 and was educated in London only to return to his native Patuxet in 1619 and find it ravaged. Tisquantum himself would die within a year of meeting the Pilgrims — while mysteriously bleeding from the nose.

Wikimedia CommonsPilgrims traveling to the New World in 1620.

That particular symptom is merely one of many attributed to leptospirosis, a zoonotic disease that experts now believe was the primary killer of Indigenous populations in 17th-century New England. The bacterium likely came to the Americans via non-native black rats transported aboard European ships.

The black rat (Rattus rattus) is the only animal that can survive a continuous leptospirosis infection in its kidney. With hundreds of thousands of bacteria in every drop of urine, the bacterium was easily deposited into regional freshwaters upon the rodent’s arrival — and rapidly spread into raccoons, muskrats, and mink.

The infection is so deadly that only 10 bacteria suffice to see a hamster hemorrhage to death after an injection. Shaped like a corkscrew, the virus burrows through red blood cells and survives by metabolizing the iron.

Typically, a robust natural human immune response often sees it multiply faster and increase the likelihood of death. This would explain why those who most commonly died from the disease were otherwise healthy people.

Wikimedia CommonsPlymouth Rock in Massachusetts marks the site of Pilgrim disembarkment in 1620.

Since prior infection doesn’t guarantee immunity, it’s unclear why the Indigenous died at a higher rate than Europeans. However, experts believe this is because the Wampanoag bathed more regularly in freshwater than settlers. They also foraged for clams and skinned beaver and deer pelts while wearing water-permeable moccasins instead of thick-soled boots.

Symptoms of infection range from fever, aches, and comparable flu signs to nosebleeds and bloodshot eyes. In the end, researchers estimate that nine out of every 10 Indigenous people infected between 1616 and 1619 were killed by it.

The Indigenous Aftermath Of European Disease

However, not all researchers believe that leptospirosis was the primary disease to blame. And although the regional soil acidity is too high for human remains to have survived for study, what’s clear is that there was a staggering mortality rate, with symptoms including yellowing of the skin, fever, congestion, and hemorrhaging.

While some of the symptoms mirrored those of the plague, no accounts ever detailed the swollen lymph nodes (or buboes) associated with it. Some have conjectured that smallpox may have been to blame, but that disease wasn’t introduced into the region until 1630.

Moreover, Rhode Island founder Roger Williams interviewed survivors of both pre and post-Pilgrim pandemics. He found that the Wampanoag differentiated between the two by using terms for “plague’ and “pox.”

Wikimedia CommonsThe Pilgrims believed the devastation of Indigenous Wampanoag was ordained by God and divined them to inhabit the land.

In 1630, Plymouth Colony Governor William Bradford began writing “Of Plymouth and Plantation.” He described the land as “a hideous and desolate wilderness full of wild beasts and wild men” with skulls and bones littering formerly populated villages. Ultimately, settlers felt warranted and ordained to take these over.

Indeed, within a decade of puritans settling the coast of Massachusetts, it’s estimated the Indigenous population fell from 30,000 to 300. Dwindling survivors were thus eager to trade, while their new invaders had no notable competition.

As Massachusetts Bay Colony Governor John Winthrop wrote in 1634, God was continuing to “drive out the natives” and is “deminishinge [sic] them as we increase.” The Pilgrim belief in their ordained colonization was only bolstered by the fact that native populations died at higher rates than Europeans.

The English initially evangelized the Indigenous and built an Indian College at Harvard in the 1650s. They believed conversion was God’s will, while the Wampanoag sought solace in the faith after decades of untold deaths.

In the end, however, the growing influx of Europeans saw the Indigenous tribes of Massachusetts dehumanized — and extinguished.

After learning about the European diseases Pilgrims brought to America, read about the truth behind who discovered America. Then, learn about the seven scariest creatures from Native American folklore.