For roughly seven months in what's known as the Prague Spring, Czechoslovakia exercised a more lax form of communism, provoking the Soviet Union and the Warsaw Pact to invade in August 1968.

From January to August in 1968, Czechoslovakia enjoyed expanded liberties and economic decentralization under the leadership of Alexander Dubček after more than two decades of Soviet-imposed communism following the end of World War II.

Known as the Prague Spring, this brief period of self-determination was short-lived after more than half a million Warsaw Pact troops were dispatched by the Soviet Union to reverse reforms and purge leaders who had instituted political changes.

The Conditions For The Prague Spring

Walter Sanders/The LIFE Picture Collection via Getty Images/Getty ImagesA parade of Soviet troops in Czechoslovakia after World War II. 1948.

Once World War II came to an end on Sept. 2, 1945, the world was left with a daunting new project: rebuilding much of Europe and Asia in the wake of destruction.

It was decided that Germany would be divided between the Americans, British, French, and Soviets, and that a committee would determine how the former Nazi state would atone for its actions. It was believed that Germany had to be divided so as not to pose a military threat. As such, the east side of the country was controlled by the Soviet Union while the west side went to the United States, United Kingdom, and France.

Meanwhile, the Soviets planned to establish a buffer zone of pro-Soviet countries in order to protect itself against Germany. This conglomeration of countries was known as the Eastern Bloc and it would come to include East Germany, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, and Albania.

While other Allies were not so comfortable with the idea of the Soviets expanding their influence in this way, they nonetheless agreed to Soviet occupation of Poland, Finland, Romania, Germany, and the Balkans if Stalin promised that he would allow those territories the right to national self-determination.

But Stalin had only loosely agreed that these countries would have this right and what exactly this right meant in the first place was never established. As such, the Eastern Bloc quickly became Soviet satellite states.

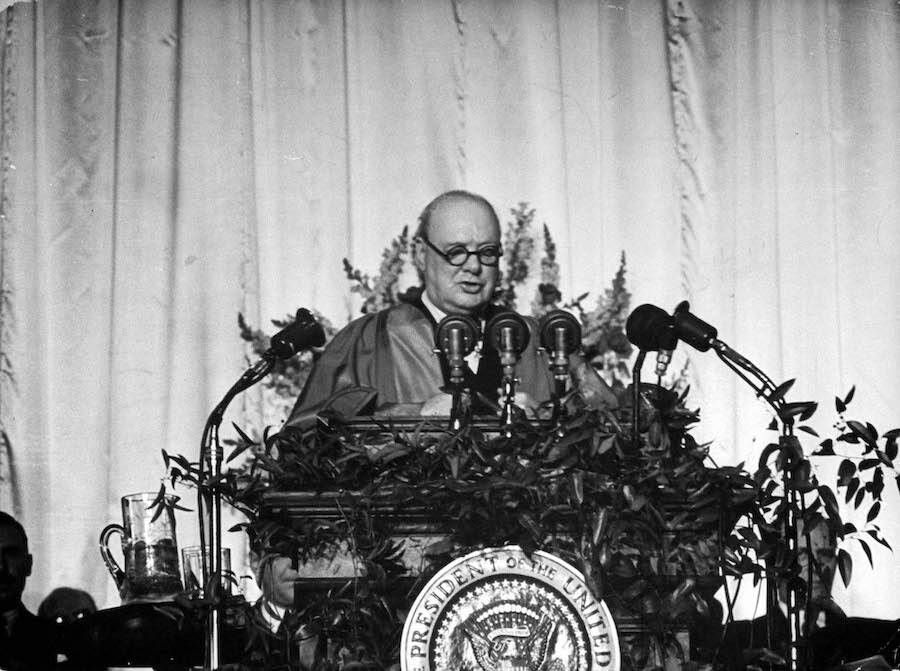

George Skadding/The LIFE Picture Collection via Getty Images/Getty ImagesBritish Prime Minister Winston Churchill during his now famous 'Iron Curtain' address.

On March 5, 1946, Churchill shared the stage with U.S. President Harry S. Truman to speak at Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri. There, he addressed the danger of the Soviet's sphere of influence in what's popularly known as the "Iron Curtain" speech.

"From Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic, an iron curtain has descended across the continent," Churchill remarked poetically about the post-war division of Europe.

The tensions between the Allies and the expanding Soviet Union became the foundation for the Cold War.

Pressing For Liberalization

As the Cold War escalated in the early 1950s, both the United States and the Soviet Union solidified their relationship with their respective allies. In 1949, the U.S. and 11 other countries signed the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) as a preemptive bulwark against Soviet or German aggression.

Keystone-France/Gamma-Keystone via Getty ImagesPolish Prime Minister Jozef Cyrankiewicz signs the Warsaw Pact.

In response to the addition of West Germany to NATO in 1955, Soviet Chairman Nikita Kruschev organized a military alliance called the Warsaw Pact between Albania, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, the territory of East Germany, Hungary, Poland, and Romania along with the Soviet Union.

It quickly became clear to Soviet territories, however, that the Warsaw Pact was not so much an alliance as it was an insurance policy. The Pact

worked to intimidate other territories into falling or remaining under Soviet power. In 1956, the countries under the Warsaw Pact were sent into Hungary to quell anti-Soviet uprisings and reinforce control.

Countries besides Hungary across the Eastern Bloc struggled to reconcile their personal identity with a strict Community regime. In Czechoslovakia, too, the heavy hand of Communism had strangled their economy. In the midst of an economic downturn in 1965, Czechoslovakia's Soviet-backed General Secretary, Antonín Novotný, sought to restructure the country's economy using a more liberal model. This inspired a country-wide call to reform other policies as well.

The Prague Spring

Sovfoto/UIG via Getty ImagesSoviet soldiers try to break through to the headquarters of the Czechoslovakia Radio but are barricaded by protesters.

Under Novotný, a new generation of Czechoslovakians arose who opposed the Soviet system. They found a leader in Alexander Dubček, a rising star in the Communist Party and a member of both central committees on the country's Czech and Slovak federations.

Dubček began to rally support from fellow reformists against Novotný until the latter finally resigned in January 1968 with Dubček quickly named in his place.

After he took office, Dubček launched a reform program called "Czechoslovakia’s Road to Socialism" in an attempt to not only slowly democratize Czechoslovakian politics but to also revitalize the country's stagnant economy.

The press now enjoyed more freedoms as did civilians while state controls were relaxed and individual rights expanded. Dubček described his platform as "socialism with a human face" as the Prague Spring swept across the country. While Dubček was careful to reassure Czechoslovakia's loyalty to the Soviet bloc, the rapidity and depth of the reforms were too much Moscow to tolerate.

In July 1968, after a meeting between the Soviet Union and other satellite states, a letter was sent to Czechoslovakia that warned against the country's continued reforms. Dubček refused to bend.

"We will keep following the direction that we started pursuing in January of this year," Dubček responded in a televised address.

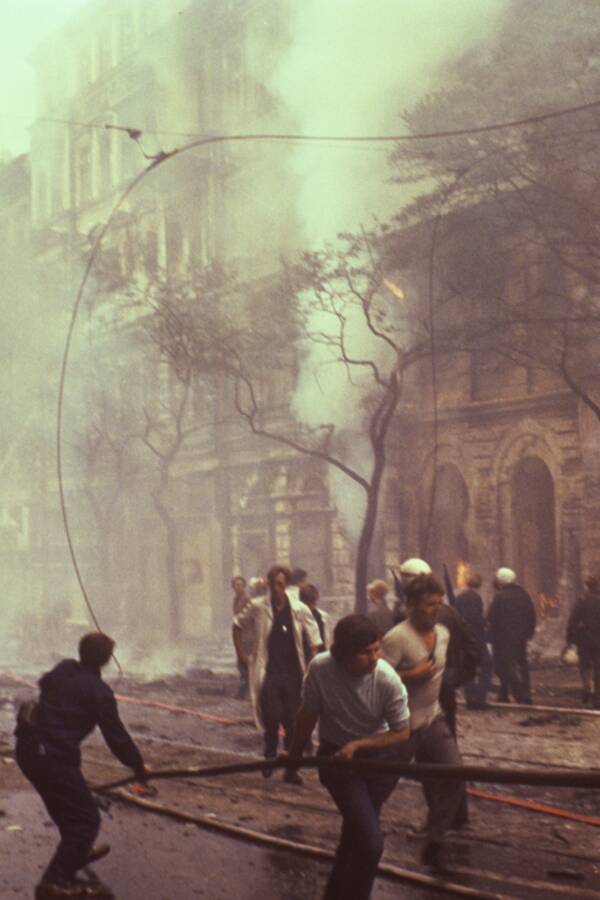

The Soviet Union responded by launching a military invasion into the country on Aug. 28, 1968, with tanks reaching the streets of Prague the same night.

Violence Ensues

More than 2,000 tanks and between 250,000 to 600,000 troops from the U.S.S.R., Hungary, Bulgaria, East Germany, and Poland invaded Czechoslovakia to put an end to the Prague Spring.

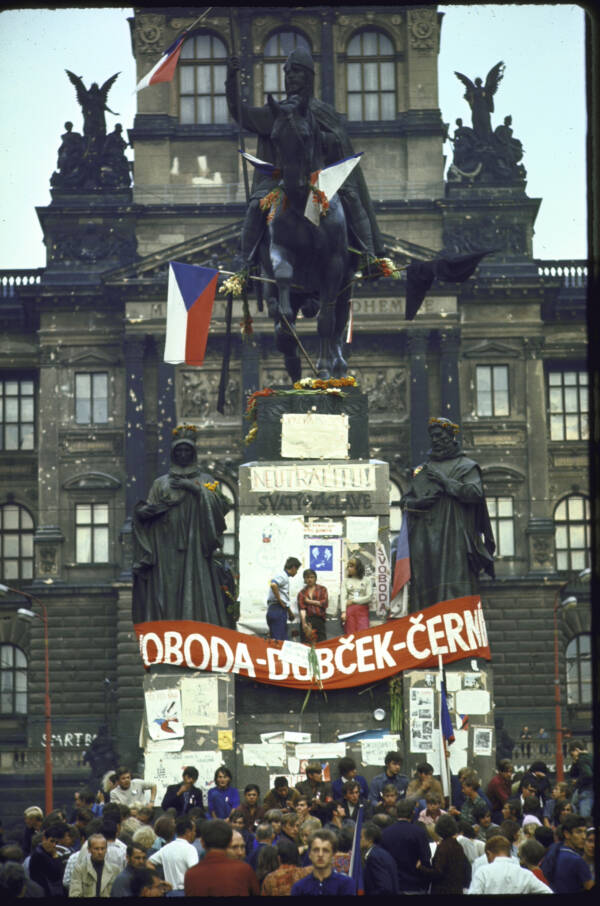

Soon, the streets of Prague, which had enjoyed at least seven months of liberalization under Dubček's reforms were riddled with unrest.

Dubček urged civilians to cooperate with Warsaw Pact forces in a broadcast over Prague's public radio.

"These may be the last reports you will hear because the technical facilities in our hands are insufficient," read the last message from the broadcast at 5 a.m.

But the people of Prague did not heed his warning. Unarmed protesters threw their bodies into the paths of the tanks anyway in an attempt to blockade the streets from the Soviet invasion. A 1990 declassified report of the Prague Spring revealed that 82 people were killed during the occupation while 300 others were seriously injured. Many of the Prague Spring victims were shot, according to the report.

Former political advisor to the Czech president Václav Havel and political analyst, Jiri Pehe, remembered the protesters on the streets:

"I still remember people going to the tanks and going to the soldiers, and talking to the soldiers who did not even know where they were, they were saying: 'This is a terrible mistake. What are you doing here? Why did you come?'"

Dubček remained defiant that the Prague Spring would survive Soviet oppression and declared, "They may crush the flowers, but they cannot stop the Spring."

Dubček and other party leaders deemed complicit in the reforms were forcibly sent to Moscow.

Alexander Dubček's Exile And The End Of The Prague Spring

Hulton Archive/Getty ImagesAlexander Dubček appeared a good compromise between the Soviet Union and Czechoslovakia as he had been trained in the U.S.S.R and locally opposed Novotny — until the public enjoyed too much freedom under his authority.

After being interrogated by Soviet Union government heads, Dubček was released and allowed to return to Czechoslovakia. Upon his return to Prague, Dubček gave an emotional address to the public.

He could not continue his speech without breaking into tears and then he went silent.

Czech journalist Margita Kollarová recalled the moment vividly:

"There was a silence... I waited and I indicated to the people around that I needed a glass of water for Mr Dubček. They brought the water. As I put the glass on the table in front of him, the sound it made brought him back to his senses. After quite a long time he began to speak again. There were tears running down his face. It was only the second time in my life that I'd seen a man cry."

Just as the Soviet curtain had broken his country's spirit, so too had Dubček been broken.

"Like all of my other schoolmates, we were raised with this idea that the system might have problems, but that it was a humane system. This was drummed into us. After 1968, this all ended. We realized this was all lies," Pehe added.

In January 1969, a 20-year-old student named Jan Palach stood in Prague's Wenceslas Square, poured gasoline on himself, and set himself on fire. It was an extreme act of protest by the young Czech over the Soviet invasion of his city.

"People have to fight against evil when they can," the badly burnt Palach had said to a psychiatrist who examined him after the incident.

Palach, who was a philosophy major, died three days later in the hospital after his self-immolation, all the while refusing to accept pain medication. His death became a wake-up call to Czechoslovakians who were desperately despaired after the Soviet occupation just five months earlier.

"After the euphoria of 1968, people had become depressed and beaten down. Palach wanted to shake them up," said Zuzana Bluh, a student leader who helped organize Palach's funeral.

An estimated 200,000 people mourned his death and marched through Prague during his funeral. Even today, a memorial in his honor is commemorated along with the anniversary of the Prague Spring.

By April, civil unrest became such that Dubček was ousted as head of the Communist Party. He was replaced by Moscow-backed Gustav Husak, whose reign was to be far more strict. Under Husak, Czechoslovakia underwent a "normalization" period during which mass purges of supporters of the Prague Spring were implemented and traveling was restricted.

Meanwhile, Dubček's political career had come to an end. After resuming the largely ceremonial position of president of parliament, Dubček was briefly made ambassador to Turkey before he was finally pushed out of the Communist Party. He then moved to Slovakia with his wife and ended up working as a clerk in a quiet corner of the Forestry Department.

Despite the turbulent end to his work in politics, Dubček remains a hero to the people of Czechoslovakia, particularly among activists in subsequent movements such as the Velvet Revolution in 1989. But his biggest legacy will always be his persistence to usher in an era of liberty for the people of Czechoslovakia in the Prague Spring, no matter how fleeting it may have been.

Now that you've caught up on the brief but glavanizing Prague Spring, take a look at these vintage Soviet propaganda posters from the era of Joseph Stalin. Next, discover 31 creepy monuments from the heydays of Communism.