During the Red Summer of 1919, white mobs — fueled by racial animosity, Communist paranoia, and yellow journalism — attacked Black communities across the United States with impunity.

Getty ImagesChildren cheer outside an African-American residence that they set on fire during the Red Summer of 1919.

Not long after World War I, a series of race riots instigated by white mobs erupted in some 25 cities in the U.S. Hundreds were killed and countless more were injured. This bloody time period would forever be known as the Red Summer of 1919.

The renewed fighting spirit of African American veterans, who suffered racial discrimination despite their military service, contributed to the Black uprisings against these white mobs. They would no longer accept the injustices that they fought so bravely against overseas in their own country.

Opposition Against Black Soldiers

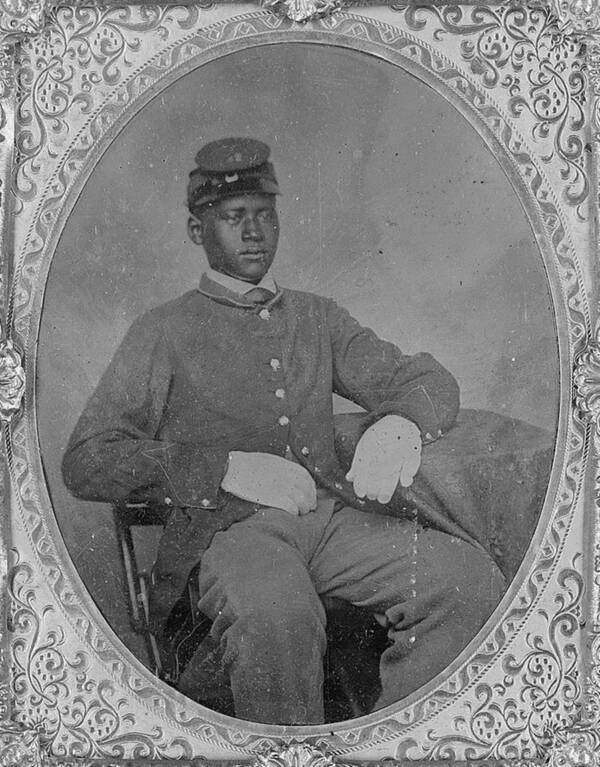

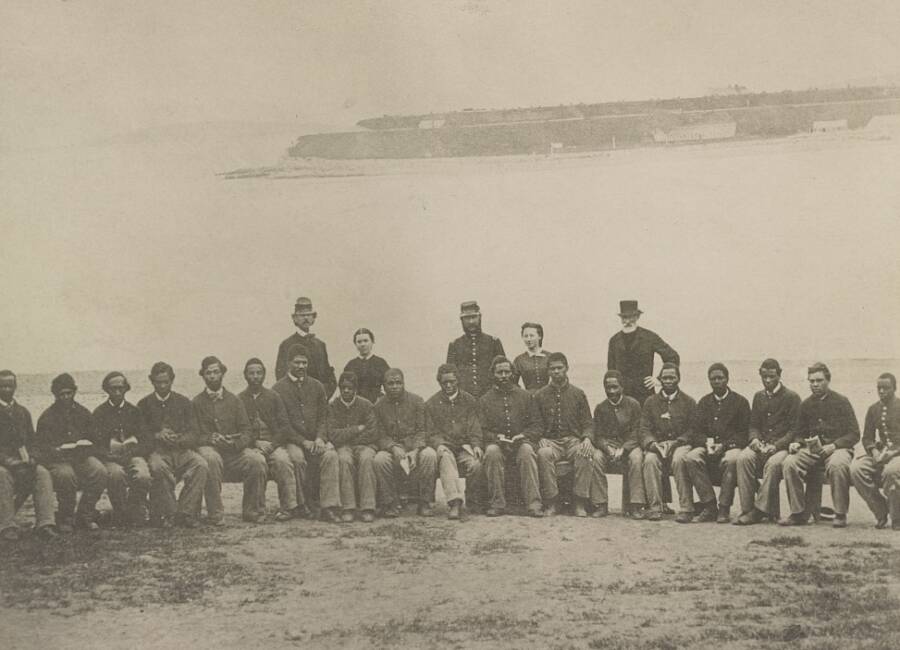

Library of CongressOn July 17, 1862, the Second Confiscation and Militia Act officially authorized the president to employ Black soldiers.

The history of Black military servicemen in America can be traced back to the Civil War, when freed Black men and formerly enslaved African Americans joined the Union Army against southern forces.

But the government’s embrace of Black soldiers came with pushback from white politicians, including President Abraham Lincoln, who rallied against the tyranny of slavery yet appeared uncomfortable with the idea of military-trained Black men.

One Ohio congressman warned, “If you make [the Black man] the instrument by which your battles are fought, the means by which your victories are won, you must treat him as a victor is entitled to be treated, with all decent and becoming respect.”

But with their resources depleted and their troops weakened, the Union had no choice. On July 17, 1862, the Second Confiscation and Militia Act officially authorized the president to accept Black members into the military.

“Once let the Black man get upon his person the brass letter…let him get an eagle on his button, and a musket on his shoulder and bullets in his pocket, there is no power on earth that can deny that he has earned the right to citizenship.”

However, African American soldiers still faced racism. Congress refused to pass legislation equalizing pay between Black and white soldiers until 1864 — two years after Black soldiers were recruited in the war.

Even after the abolition of slavery in 1865, Black veterans were still subjected to racial violence from white society.

As explained by the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) in their report Lynching in America: Targeting Black Veterans, which documented over 4,000 lynchings of African Americans between 1877 and 1950, “Black veterans were seen as a particularly strong threat to racial hierarchy and were an early target of discriminatory state laws.”

Library of CongressRacist laws in some states prevented Black veterans from owning firearms after the Civil War ended.

Gun ownership among Black residents reached an unprecedented high due to the war, so several states enacted legislation prohibiting African Americans from possessing firearms.

Florida’s Black Code of 1866, for instance, prohibited Black people from possessing “any Bowie-knife, dirk sword, firearms, or ammunition of any kind.” Any violations of the code could be punishable by a public whipping.

This discrimination against Black soldiers and veterans continued in the aftermath of other wars that the U.S. got involved in, including World War I.

Red Summer Of 1919

Wikimedia CommonsMembers of the “Harlem Hellfighters” military unit of World War I were honored by the French. But when they returned to the U.S., they faced racial discrimination and violence.

During World War I, African American soldiers were deployed through segregated units across Europe. Perhaps the most famous unit was the Harlem Hellfighters, the all-Black 369th Infantry Regiment of the U.S. Army, who fought off German forces in France.

Private Henry Johnson was awarded the Croix de Guerre avec Palme, the highest award for valor in France, for his service with the Hellfighters. But when Johnson and other Black soldiers returned home to the U.S., they came back to racial discrimination and violence.

In the summer of 1919, just after the end of World War I, anti-Black riots erupted across the country. There were at least 25 of these riots in cities like Chicago, Charleston, and Tulsa.

Chicago History MuseumFront page of the Chicago Defender on Aug. 2, 1919, listing the names of those who were slain and injured during the race riots in Chicago.

Many African Americans had begun migrating to the urban cities of the north to seek better opportunities and escape the brutal racism of the rural south in the early 1900s. This was known as the Great Migration. But this influx of Black populations angered white residents in the north.

Adding to escalating racial tensions was the return of African American soldiers after World War I. An estimated 100,000 Black veterans moved north after their service.

“The struggle over jobs, the return of Black soldiers from the war and not being treated with respect and not finding employment — those tensions were in so many places,” said Liesl Olson, the director of the Chicago History project at the Newberry Library.

On top of that, the nationwide paranoia about Communism and anarchy taking over the world only added to this growing tension in the United States. Before long, violence broke out.

Despite the fact that it’s called the Red Summer of 1919, the riots actually stretched from late winter to early autumn of that year.

One of the most significant riots happened in Washington, D.C. on July 19, 1919. A rumor that a Black man had assaulted a white woman triggered an invasion of white mobs into Black neighborhoods. Not only did they try to destroy the communities, they also started randomly attacking Black residents on the streets.

One of the first victims of the Red Summer riots in Washington D.C. was a 22-year-old Black veteran named Randall Neale.

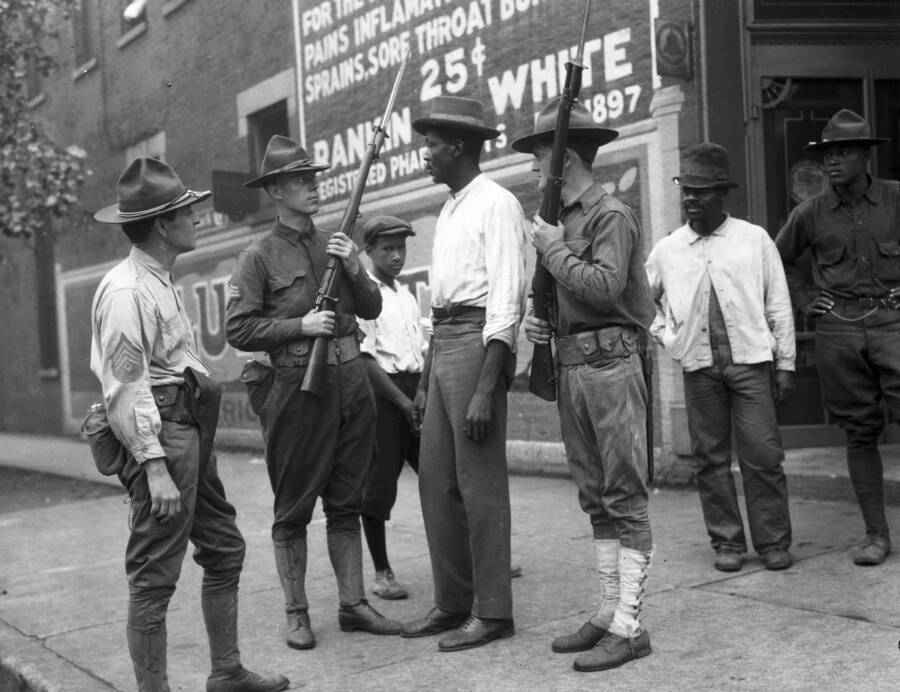

In nearby Norfolk, Virginia, a parade honoring the return of African American servicemen also turned violent. Local authorities were so overwhelmed that President Woodrow Wilson actually had to send in troops to secure the streets. Two Black soldiers were killed during this conflict.

Perhaps the most infamous riot of the Red Summer of 1919 happened in Chicago. On July 27, 1919, violence erupted after the death of a Black teenager who had drowned after being hit with stones when he drifted near a white beach. This unrest went on for several days.

By the end of the Chicago riots, 38 people — Black and white — were killed in the city while 537 others were injured. At least 1,000 Black homes were burned down or destroyed.

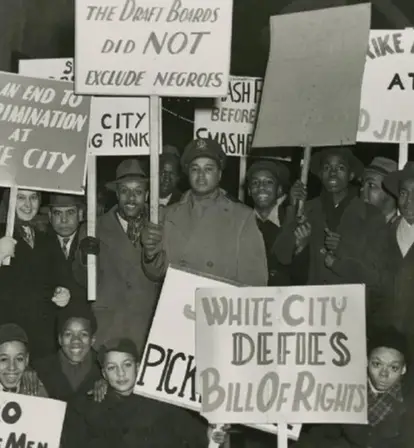

Black Soldiers Fight Back Against Racism

Chicago History MuseumThe long-delayed intervention of the Illinois National Guard finally brought the violence of the Red Summer riots in Chicago to a halt.

Historians believe the resolution of Black veterans who risked their lives fighting for basic human rights abroad emboldened them to fight against racial discrimination at home as well.

George Edmund Haynes, who completed a report on the violence of the Red Summer in the fall of 1919, concluded that “the persistence of unpunished lynching” contributed to the mob mentality among white men but also fueled a new commitment to self-defense among Black men, particularly veterans of the war.

But even at the end of the summer, violence against African Americans raged on. On Sept. 28, 1919, thousands of white people descended on the Douglas County Courthouse in Omaha to lynch William Brown, a Black man who was detained after being accused of assaulting a white woman.

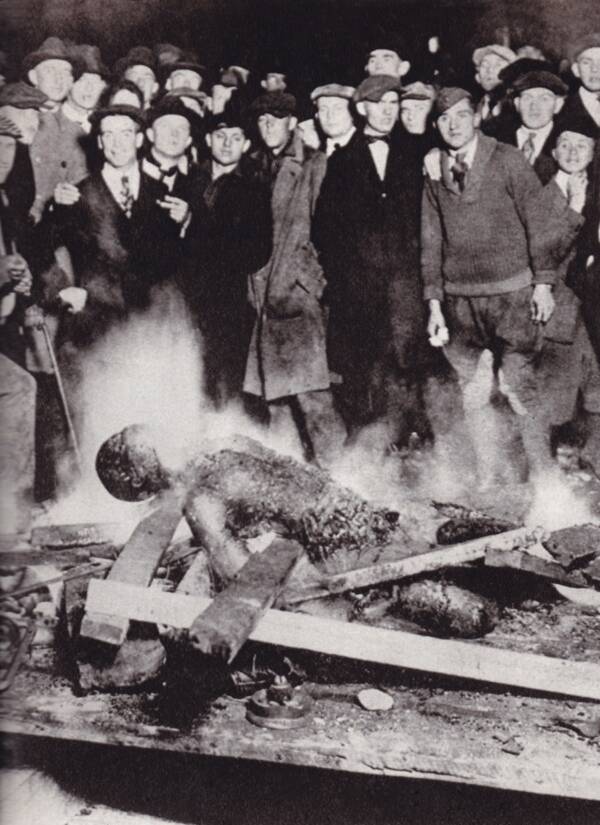

SeM/Universal Images Group via Getty ImagesThe white mob that killed William Brown poses for a photo as they burn his lynched body in the street during the Omaha race riot in 1919.

The mob dragged Brown out of the courthouse, beat him, then hung him from a telegraph pole and shot his dead body multiple times. Then, they dragged his body through the streets before setting it ablaze.

The Red Summer of 1919 remains notable not only because of the intensity of violence that erupted, but also because of the perseverance of Black veterans who defended their communities against the white mobs.

Wikimedia CommonsFlag of the old 15th (left) decorated by the French and the American flag.

The Washington Bee reported that those fighting back against the violent white mobs included Black veterans “who had served with distinction in France, some of whom had been wounded fighting to make the world safe for democracy.”

During the riots in Washington, D.C., Black residents took up arms to defend their homes, unable to rely on police who may well have shared the white mob mentality. In Chicago, African American veterans broke into an armory and armed themselves with weapons to protect their neighbors.

Despite the horrific injustices Black veterans faced, these soldiers were committed to rightfully defend their liberty and, as the EJI report noted, “remained determined to fight at home for what they had helped to achieve abroad.”

Now that you’ve uncovered the true story of the Red Summer of 1919, learn about the horrific Tulsa race riots, when white mobs descended on Black Wall Street. Next, discover the horrifying history of the syphilis experiment performed on Black Tuskegee servicemen.