A year after his wife's disappearance, the Dutch crime author showed his publisher a grisly manuscript that consequently turned him into a cult celebrity of sorts.

Richard Klinkhamer enjoyed a bit of fame after he proposed a book detailing the seven grisly ways in which he could’ve murdered his wife.

In 1991, Dutch crime author Richard Klinkhamer became the subject of public speculation after the suspicious disappearance of his wife made national news in the Netherlands — and he became a prime suspect.

Though detained once, Klinkhamer was not charged, and he soon thereafter proposed a book outlining the different ways in which he could have murdered his wife. The book was rejected and Klinkhamer relocated to Amsterdam.

Shortly after the new tenants began renovations on his old garden, they made a grisly discovery that cemented Klinhamer’s case as one of the most notorious in the country’s recent history.

The Bleak Background Of Richard Klinkhamer

Wikimedia CommonsSix years after his wife vanished, Richard Klinkhamer moved to Amsterdam.

Born on March 15, 1937, Richard Klinkhamer had a rough upbringing. When he was five years old he witnessed his aunt’s rape and the murder of his uncle.

Klinkhamer lived in Austria at the start of World War II and recalled to his editor Willem Donker that his mother had an affair with an SS officer. She was also raped by a Nazi, however, and upon returning to Holland punished for it by the Dutch public who shaved her head in an ugly carnival.

To make ends meet after the war, his mother worked as a prostitute while young Klinkhamer went in-and-out of foster care. When he turned 19, Klinkhamer joined the French Foreign Legion, a branch of the French Army made up of foreign volunteer misfits.

Richard Klinkhamer later became an auditor and turned to writing. He got married, divorced, developed a drinking habit, and landed in Amsterdam where he met his future wife, Hannelore Godfrinon.

According to her friends, Hanny, as she was fondly called, described Klinkhamer as entertaining and funny. She was 10 years younger than he and they barely knew each other, but she didn’t care.

“She was obsessed by Klinkhamer,” Harry Wieters, one of Hanny’s friends who later became the best man at their wedding, recalled to The Guardian.

In 1978, the two married and moved to the little hamlet of Ganzedijk in the northeastern Netherlands. At first, the marriage was stable. Both had good jobs, Hanny as a nurse and Klinkhamer as a writer, and they often socialized with friends.

But after Klinkhamer lost their savings in a bad stock market dealing, he delved into heavy drinking that quickly dissolved their marital bliss.

According to Wieters, Hanny often stayed with friends when her husband was having violent, drunken fits. Because of this, her friends would later become immediately suspicious of the abusive Klinkhamer when Hanny suddenly disappeared in ’91.

When in February 1991 Richard Klinkhamer reported his wife’s disappearance to police after telling them he had found her red bicycle at a nearby train station, Hanny’s friends were already convinced that the writer was responsible.

“He did not look for her,” remembered Janny Berkhemer who worked at the same hospital as Hanny.

Friends told authorities about the married couple’s violent quarrels, but an extensive search of the house by investigators — with the help of sniffer dogs and infrared aerial scanning by Royal Dutch aircraft — came up empty.

Without any evidence to tie him to the case, the police had no basis for a murder inquiry into Klinkhamer.

After he was let go as a suspect, Richard Klinkhamer continued to live alone, writing and drinking profusely in their house in Ganzedijk.

A Suspicious Manuscript

Despite people’s suspicions that Klinkhamer had killed his wife, his writing was embraced — and even adored — by many.

A year after his wife had mysteriously vanished, Richard Klinkhamer visited his publisher, Willem Donker, with a new manuscript.

Klinkhamer had achieved a modicum of fame after the release of his first two crime dramas, Obedient as a Dog and Hotel Red. The former drew heavily on his experience as a trained killer for the French Foreign Legion.

But this time, Klinkhamer’s proposal to his publisher was even more macabre. Titled Woensdag Gehaktdag after a Dutch saying which translates to “Wednesday, Mince Day,” the novel was a grisly list of ways in which Klinkhamer could have killed his wife.

Of the seven methods outlined in his manuscript, one of the goriest was destroying Hanny’s body by pushing her corpse through a meat grinder then feeding the bits to pigeons. The book was so morbid, in fact, that Donker rejected it.

Naturally, Donker became suspicious of Klinkhamer around this time and asked him point-blank whether he had actually killed his wife.

“It’s not yet the time to talk about it,” Klinkhamer answered vaguely.

Donker then advised the author to expand on a section of the disturbing manuscript which resulted in his third novel, Ransom, which was about an art heist.

But word about Klinkhamer’s suspicious book proposal soon got out to the public, mostly among the local press. The gossip resulted in television interviews including on one program about eccentric figures called Birds Of Paradise.

When the show’s host asked Klinkhamer whether he had killed his wife, the writer replied casually, “It could be…The villagers say I cut her into pieces or put her in the pond…”

Klinkhamer fueled the rumors himself. He said damning things like, “Everyone is able to murder someone, somewhere, suddenly.” He once dug a hole in his garden and pointed out to neighbors that it was big enough for a person’s body.

“He loved the notoriety,” Donker said. “But at the same time, he told me his wife was the greatest love of his life.”

John Schoor, a journalist with Dutch paper De Volksrant, visited Richard Klinkhamer after he moved back to Amsterdam in 1997.

Schoor described the author’s demeanor as “spooky” and said he “was really working with the fear of people. He made a lot of jokes about dark things, death.”

Little did Richard Klinkhamer know that his games and jokes would catch up with him.

The Discovery Of Hannelore’s Body

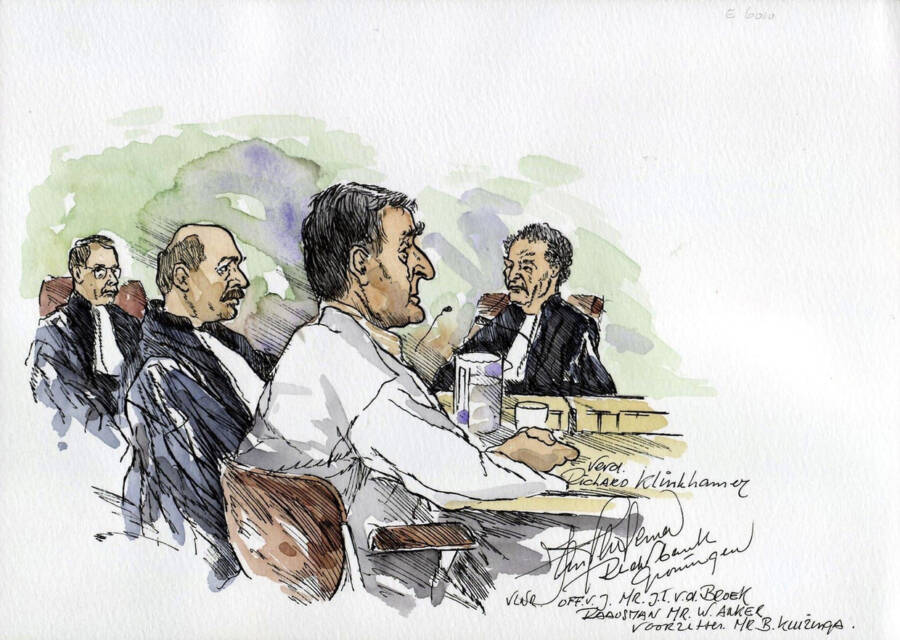

Beeld anpA sketch of Richard Klinkhamer’s 2001 trial, almost a decade after he killed Hannelore.

Six years after his wife went missing, Richard Klinkhamer hired a lawyer so that he could legally pronounce her dead and sell the house which had been in her name. Then he moved back to Amsterdam and began to collect a widower’s pension.

The new owners of the house, meanwhile, began deconstructing the home’s 200-square-foot garden. That’s when construction workers accidentally came across a piece of clay buried beneath the garden shed’s concrete floor.

Inside they found a human skull. It was soon confirmed by a forensic scientist to belong to Hannelore Klinkhamer.

Local authorities arrested Richard Klinkhamer that evening. According to Klinkhamer’s own account of those events on Jan. 31, 1991, he had beat his wife to death with a wrench before he buried her underneath the shed.

He used compost to disguise the smell of rotting flesh.

While he awaited trial from his jail cell in Utrecht, Richard Klinkhamer told People magazine that the couple had gotten into a nasty argument on the night he killed her. He claimed Hanny had grabbed a wrench and they began to wrestle:

“From that moment on, I don’t remember much. She hit my hand, we wrestled and came to the back door. That’s where it happened. She was yelling, screaming—never stopped screaming…It’s haunting me still.”

Richard Klinkhamer was sentenced to seven years in prison for his wife’s murder but was later released in 2003 after only two years for good behavior.

In January 2016, the freed murderer committed suicide and died at the age of 78.

Klinkhamer’s guilt was an anti-climatic reveal to what many had known all along. Yet, almost a decade had passed before he faced justice.

More troubling than the murder itself was perhaps the cult fame that had formed around him.

His neighbors still embraced him without judgment.

“Richard Klinkhamer was an eccentric man but in our eyes a good man,” said Coos Molenaar, who lived across from him in Amsterdam’s Bijlmermeer district. Klinkhamer had even landed himself a new girlfriend who was 35 years his junior.

In 2001, that girlfriend said: “Although a lot of people are very shocked, all of his friends here in Amsterdam know what he is like, and so this doesn’t change anything for us.”

Then she added: “Only my father has said to me, ‘Now that all of this has happened, you should be glad that he didn’t kill you.'”

Next up, check out the story of Mitchel Quy, who killed his wife then pretended to “look” for her in front of the media. Then, meet Pedro Rodrigues Filho, the real-life “Dexter” — who killed other criminals.