King Henry II was so delighted by the simultaneous jump, whistle, and fart that Roland performed that he awarded his court jester a manor house and 30 acres of land.

Public DomainA 16th-century woodcut of a jester.

In a sea of medieval jesters, Roland the Farter stands out as one of the most unique performers in history.

Roland the Farter, or Roland le Petour, was a 12th-century jester known for his comedic acts involving flatulence. He captivated the court of King Henry II, and his performances earned him entitlements uncommon for someone of his social status.

In exchange for performing a simultaneous jump, whistle, and fart for the king each Christmas, Roland was awarded a manor house and 30 acres of land in Suffolk. Little else is known about his life, but it’s evident that he was a royal favorite.

Inside The Life Of A Medieval Court Jester

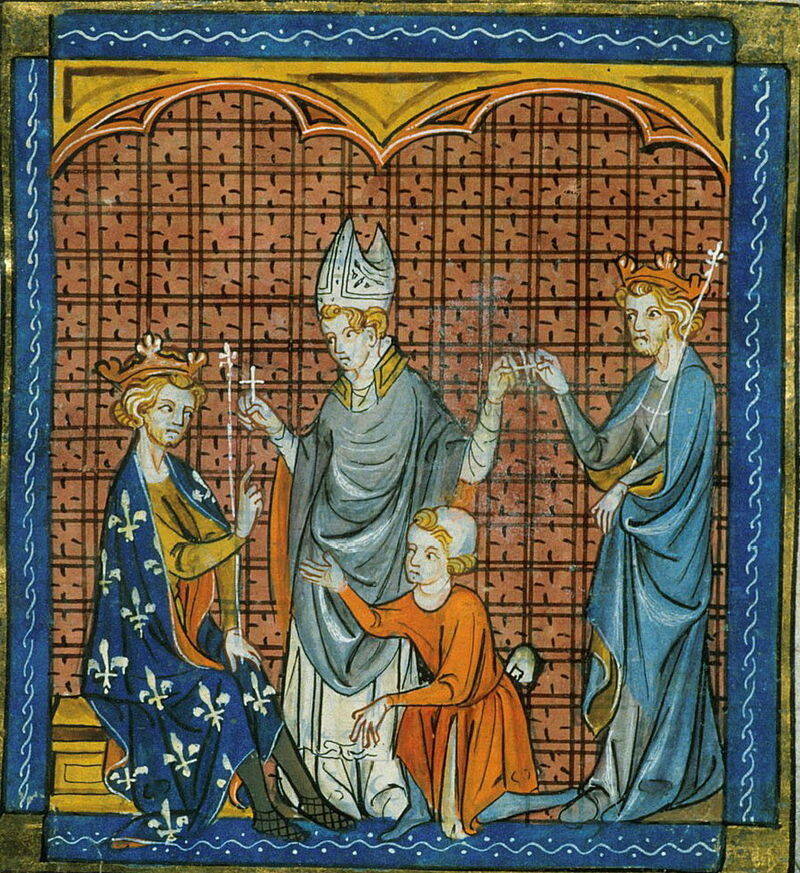

Public Domain William Merritt Chase’s Keying Up: The Court Jester (c. 1875).

Before exploring the life of Roland the Farter, it is important to understand that jesters were not the silly clowns we see them as today. Instead, they were valued by members from all levels of society. Whether performing in royal courts or in street fairs, jesters brought joy to struggling people.

Jesters were highly skilled performers with talents like singing, dancing, playing musical instruments, performing magic tricks, and making people laugh with their quick wit. Oftentimes, they were overtly political, joking about current events and people who were familiar to their audiences. Indeed, they had the power to say things no one else could without facing punishment.

The history of the jester dates back thousands of years. In ancient Rome, jesters called balatrones amused wealthy elites with clever wordplay and satirical wit. Other evidence of jesters has appeared in Persia, China, and even the Aztec Empire.

Jesters may have spread throughout Europe as they faced persecution in Rome. As Beatrice K. Otto wrote in her book Fools Are Everywhere: The Court Jester Around the World, “With periodic imperial purges against actors for their outspokenness, many of them took to the road and fanned out across the empire in search of new audiences and greater freedom. Successive waves of such wandering comics may well have laid the foundations for medieval and Renaissance jesterdom, possibly contributing to the rising tide of folly worship that swept across the Continent from the late Middle Ages.”

Jesters were certainly a common sight at English royal courts by medieval times. Their daily lives outside of performing included preparing for future entertainments, socializing with other members of the court, and enjoying meals with fellow staff. While they enjoyed close proximity to society’s elites, they were not considered to be in the same social class — making the accomplishments and titles of Roland the Farter all the more impressive.

What Do We Know About Roland The Farter?

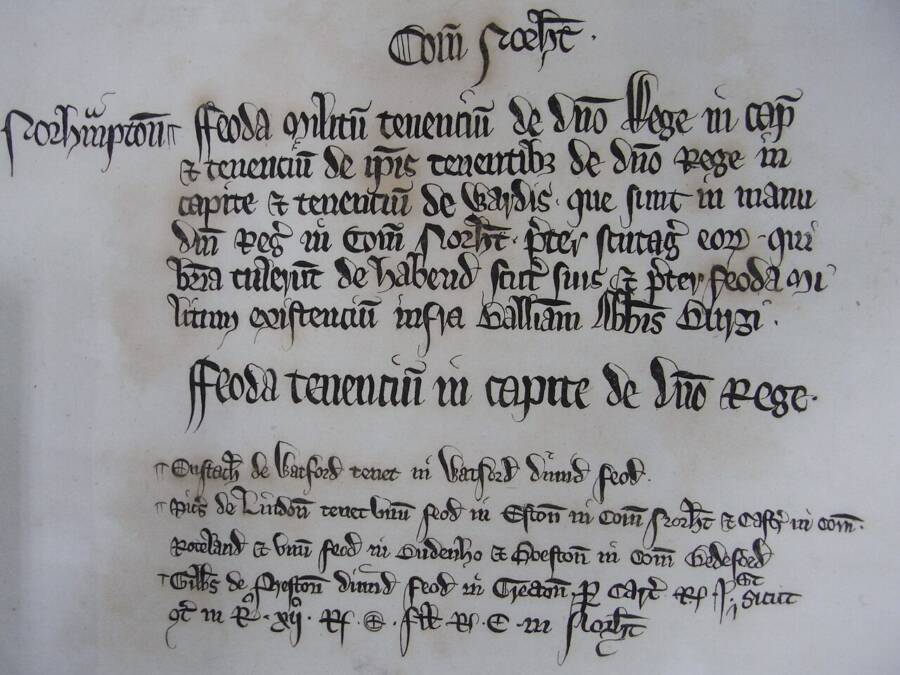

Public DomainA 14th-century depiction of Henry II taking the cross for the Third Crusade.

Roland the Farter appears in the historical record only briefly, but it’s evident that he performed, at the very least, for King Henry II during the 12th century. Some sources speculate that he may have been employed at the court of Henry I as well, but the first mention of the jester is from 1159, when Henry II was already on the throne.

It is unclear where and when Roland the Farter was born or how he came to be a jester for the English royal family. It is only known that Henry II agreed to transfer a manor house and 30 acres in Suffolk to Roland in 1159 in exchange for a performance each Christmas. This property was awarded via serjeanty, a type of feudal tenure in which the receiver could keep the land as long as they carried out a specific duty for a monarch.

Roland’s duty was bizarre. As it was recorded in the 13th-century Liber feodorum, or Book of Fees, Roland had to perform “unum saltum et siffletum et unum bumbulum” — a simultaneous jump, whistle, and fart — for Henry II each year on Christmas.

G3n3r41ch3/Wikimedia CommonsRoland the Farter is included in the Book of Fees, a listing of feudal landholdings.

Some sources say Roland actually received 110 acres, which would be the equivalent of one-fifth of a knight’s fee — just for farting.

Roland the Farter’s fate is ultimately unknown. Some say he was dismissed by Henry III because his skill was deemed “indecent,” but it’s unlikely that he was alive by the time the king took the throne in 1216. Even if he were just 20 years old when he started working for Henry II in 1159, he would have been in his late 70s by Henry III’s rule.

What’s more, Roland’s son, Hubert de Afleton, seemingly took control of the manor and land sometime before 1189, suggesting that the jester had died by then. However, at some point, Roland was no longer obliged to pass gas for royalty, the serjeanty came to an end, and his heirs paid cash for the property instead.

Many questions remain about the life of Roland the Farter — including how his strange performance came to be in the first place.

Roland The Farter’s Art Of Flatulism

Public DomainA jester in John Dawson Watson’s Friends in Council (1877).

Roland the Farter rose to prominence in Henry II’s court as a flatulist, a performer who uses farts as a punchline. While it may sound strange to dedicate a whole profession to passing gas, it was a particularly popular act among jesters.

As Valerie Allen, the author of a comprehensive historical account of Roland the Farter, explained in her book On Farting: Language and Laughter in the Middle Ages, the naturally funny nature of flatulence provided a quick and easy way for jesters to entertain and relate to their guests.

However, it also had a deeper meaning. Allen wrote, “Gas is the product of decomposition, so morally, theologically, a lot of the writers in the Middle Ages saw it as the mark of death. There was a lot of moralization about farts and [human excrement], that they are the living daily reminder that we are going to die and that’s all we are, we are mortal, and sinful as well.”

Of course, flatulists weren’t just limited to English courts. Saint Augustine mentioned performers with “such command of their bowels, that they can break wind continuously at will, so as to produce the effect of singing” in his fifth-century C.E. work The City of God. In medieval Ireland, professional farters called braigetoír entertained royalty alongside bards and harpers.

Flatulists also appeared in Japan during the Edo period (1600 to 1868), where they were known as heppiri otoko, or “farting men.” Scrolls from the time even depict “farting competitions.”

However, none of these flatulists could hold a candle to the level of influence Roland the Farter maintained. For that, he remains one of a kind.

After reading about the strange story of Roland the Farter, go inside the tale of Triboulet, a 16th-century French jester whose life was saved by his wit. Then, discover another strange story from 12th-century England: the legend of the Green Children of Woolpit.