Due to the religious significance of Saint Eanswythe, scientists could only analyze them in the church.

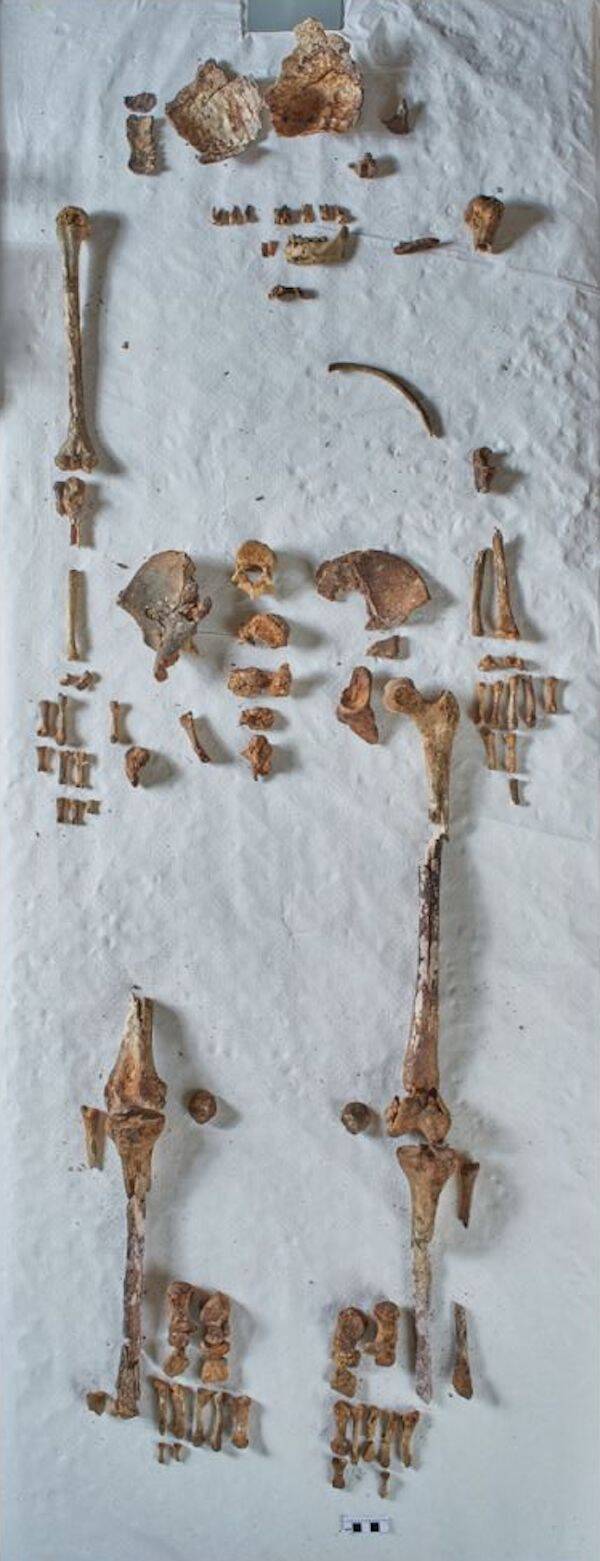

Mark HourahaneResearchers were not allowed to take Saint Eanswythe’s remains out of the church.

When workers discovered human bones behind a church wall in southern England in 1885, they couldn’t confirm what they’d found. But upon analysis more than 100 years later, it’s been confirmed that the remains belonged to one of England’s earliest saints.

Found in the Church of St. Mary and St. Eanswythe in Folkestone, England, the remains were never properly analyzed until now. Though some suspected they might be Saint Eanswythe’s, experts have only now officially confirmed they indeed belonged to her.

According to Live Science, Eanswythe was even more impressive than her title implied, as she was a princess and the granddaughter of Ethelbert to boot. Ethelbert was the first Christian king of Kent, and he ruled eastern England from 580 A.D. until his death in 616 A.D.

Saint Eanswythe’s bones were most likely tucked away behind the church wall to protect them from destruction during the Protestant Reformation. They are now England’s earliest verified remains of a saint ever discovered.

Matt RoweThe remains were likely concealed behind the church wall to prevent their destruction during the Protestant Reformation.

While her exact birth year remains unclear, historians agree it probably fell between 630 A.D. and 640 A.D. — which coincided with the rise of Christianity in England. Her father built the young girl a monastery in Folkestone, which she joined at age 16.

Not only was this the first monastery for women in England, but Eanswythe also became its abbess at some point before she died. According to Andrew Richardson, an archaeologist with the Canterbury Archaeological Trust, Eanswythe died sometime between 653 and 663 A.D.

He believes it was her unprecedented accomplishments that garnered her recognition as a saint.

“I suspect that her early death at such a young age — 17 to 20, 22 at the most — perhaps just after becoming the founding abbess of one of England’s first monastic institutions that included women, plus the fact that she was of the Kentish royal house (beloved by the Church as the first to convert to Christianity), would have easily been enough to get her acclaimed as a saint, perhaps within only a few years of her death,” he said.

“She was, though, along with her aunt Ethelburga, the first of the female English saints.”

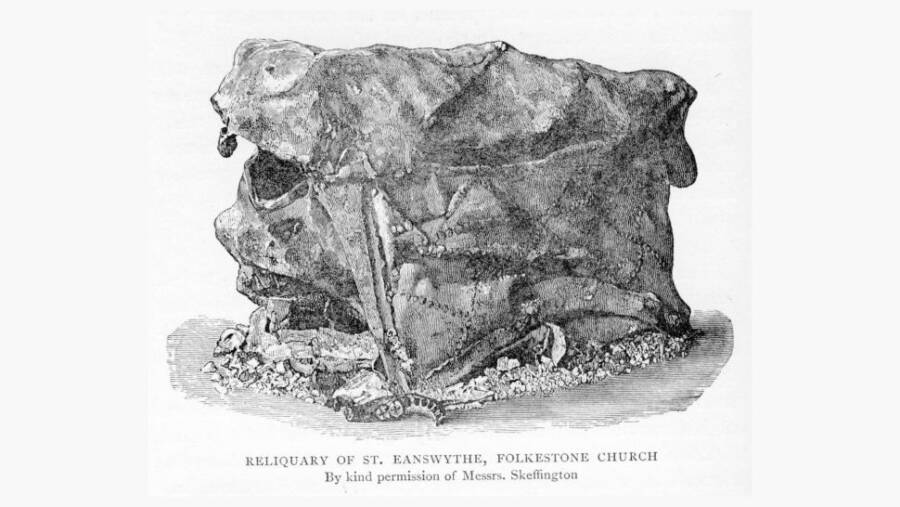

Canterbury Historical & Archaeological Society (CHAS)The royal was one of the first female saints of England.

When workers discovered the bones in 1885, they were simply removing plaster from the Folkestone church’s northern wall. As The New York Times reported on August 9, 1885:

“Taking away a layer of rubble and broken tiles, a cavity was discovered, and in this [was found] a broken and corroded leaden casket, oval shaped, about 18 inches [46 centimeters] long and 12 inches [31 cm] broad, the sides being about 10 inches [25 cm] high.”

As for the remains found within, the bones were “in such a crumbling condition that the vicar declined to allow them to be touched except by experts.” Even now, 135 years later, officials imposed several rules for scientists handling Saint Eanswythe’s remains.

For instance, the bones were not allowed to be removed from the church reliquary for this recent analysis, leading researchers to set up shop inside the house of worship. Some of them even slept there overnight to get the job done.

As for the analysis itself, radiocarbon dating of tooth and bone samples confirmed she died in the mid-seventh century. Plus, numerous historic records from the 10th to 16th century referenced Folkestone as Saint Eanswythe’s final resting place — further indicating the bones were hers.

Kent Archaeological SocietyThe bones were discovered within a church in 1885, but hadn’t been rigorously analyzed until recently.

“We know there was a shrine to her until the 1530s, when the church at Folkestone (which was a priory with monks) surrendered to Henry VIII’s men,” Richardson explained. “It was usual at that point that any shrines or relics would be destroyed.”

“But in this case, her bones were concealed in a lead container in the wall beneath her shrine. When this was discovered by workmen in June 1885, it was immediately thought the remains might be hers.”

For Richardson, bone analysis, radiocarbon dating, and the historic records are certainly indicators enough that the remains belonged to Saint Eanswythe. On the other hand, he believes the simple burial place is sufficient to wager a strong guess.

“It is actually quite hard to see a more plausible reason why a young woman who died in the mid-seventh century was found concealed in the wall of a 12th-century church, below what was probably the location of St. Eanswythe’s medieval shrine,” he said.

As it stands, researchers plan on more rigorous testing of the bones including genetic analysis, as well as an analysis of the atomic elements within. This will not only give officials more information, but also help them assess how these remains should be preserved and displayed — if at all.

After learning about the bones discovered behind a church wall belonging to one of England’s earliest saints, read about the bones of St. Peter being found in a thousand-year-old church. Then, learn about researchers finding the oldest-ever bracelet alongside an extinct human species.