Wordsmith, wit, and secret masochist Samuel Johnson overcame a host of ailments and financial struggles to write his masterpiece, A Dictionary of the English Language.

Dr. Samuel Johnson arguably contributed more to the English language than any other person. A poet, playwright, essayist, critic, and biographer, what set him apart was A Dictionary of the English Language. Produced almost single-handedly and published in 1755, Johnson’s tome would remain the preeminent English dictionary for more than 150 years.

The mammoth endeavor comprised more than 42,000 individual entries — and took Johnson only eight years to complete. That would be a feat for anyone, but it was especially impressive for Johnson: Although he was already a celebrated writer, he also dealt with a plethora of physical ailments and mental health issues, as well as financial strife in his younger years.

A college dropout with money woes and no guarantees he’d ever become more than a cash-strapped poet, Johnson’s discipline, dedication, and sheer ambition landed him firmly in the history books as one of the great contributors to English language and literature. After he finally achieved some success, he spent his days communing with some of England’s most interesting people — and writing salacious letters to a mistress 30 years his junior.

Let’s take a look at the fascinating life of this prolific wordsmith.

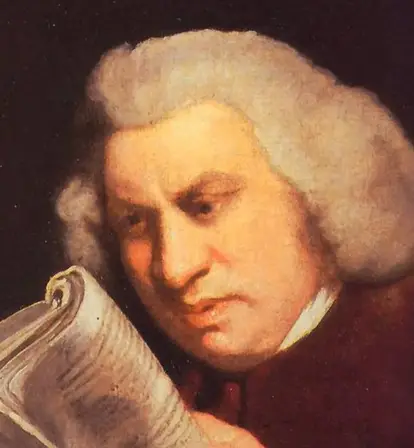

Wikimedia CommonsA portrait of Samuel Johnson by Joshua Reynolds. 1772.

Early Childhood And Health Issues

Johnson was born on Sept. 18, 1709, in Lichfield, England to Michael Johnson and Sarah Ford. Michael owned a bookshop on the ground floor of their four-story house on the corner of Breadmarket Street and Market Square. Like his son would do years later, Michael wrote some books, but ultimately settled as a shopkeeper and local sheriff.

The pair had another son three years later, but not much is known about him besides the fact that he and his brother Samuel were never very close.

Wikimedia CommonsSamuel Johnson’s birthplace is now a museum.

Samuel Johnson was placed in the care of a wet nurse soon after he was born, and suffered almost immediately from a variety of health issues. The nurse’s breastmilk was infected with tuberculosis and Johnson contracted scrofula which inflamed his lymph nodes, leaving him partially deaf and nearly blind in his left eye.

Doctors operated on the glands in his neck, leaving scars, and he also suffered from a bout of smallpox. Things only worsened as he got older, when he began to exhibit peculiar tics and convulsions. These quirks may have come from the diseases he suffered as an infant, or may have been the result of Tourette syndrome, a disorder which scientists wouldn’t identify until the following century.

Wikimedia CommonsWorried about her son’s ailments, Johnson’s mother took him to get “touched” by Queen Anne in hopes his health would improve. Above, a portrait of Queen Anne by Michael Dahl. 1705.

His dreadfully worried mother took him to London in March 1712, when he was two years old, so he could be “touched” by Queen Anne in hopes of improving his ailments. The queen gifted the family a golden “touchpiece,” which Johnson wore around his neck until he died.

Samuel Johnson: Literary Prodigy

Samuel Johnson’s mother taught him how to read before he joined the ancient grammar school of Lichfield in 1717. After studying Latin for two years, he joined the upper school and studied under headmaster John Hunter, whom Johnson found “very severe, and wrong-headedly severe.”

Needless to say, although Johnson was brilliant, he despised formal schooling. In fact, in his dictionary, he defined school as a “house of discipline and instruction.”

Wikimedia CommonsJohnson attended the King Edward VI School in 1726 and tutored younger students for extra money.

Outside of school, Johnson began scouring his father’s bookstore for works outside the syllabus, developing a self-taught savvy of classical literature.

When Johnson joined the King Edward VI School in June 1726, he translated Latin works by Horace and Virgil, wrote poetry, and taught the younger students for some extra cash. But after only a few months, his physical ailments forced him to leave school.

The next two years became what he thought of as lost years, although he did read everything he could get his hands on — voraciously.

But as his father’s financial situation worsened, it became clear Johnson wouldn’t be able to attend college. Fortunately, he found an opportunity for tutelage by his cousin, Cornelius Ford.

A scholar 14 years his senior, Ford exposed his cousin to English playwrights and poets like Samuel Garth, Matthew Prior, and William Congreve — whose works Johnson would later quote in his dictionary.

Miraculously, with financial help from his mother, who inherited some money from her cousin, Johnson managed to go to begin college at Oxford.

Oxford, Unemployment, And Marriage

Johnson was accepted to Pembroke College, Oxford on Oct. 31, 1728. The studious young lad had just turned 19, and though he was eager to advance his academic career, he only stayed at the school for a little over a year.

Johnson’s time at Pembroke ended when he was forced to leave due to lack of funds. His mother’s money wasn’t quite cutting it, and the assistance he had been promised from a wealthy former schoolmate didn’t come through. He would be awarded an honorary degree after publishing his dictionary decades later, but was forced to go back to Lichfield when he was 20 years old.

Johnson tried finding employment as a teacher, but quickly realized he had no passion for the job. His afflictions became increasingly debilitating, and both mentally exhausted and physically pained him. Posthumously, he’d be diagnosed with clinical depression. His Tourette’s also became more noticeable during these years.

Wikimedia CommonsJohnson attended Pembroke College at Oxford for about a year before lack of funds forced him to drop out. He was later awarded an honorary degree.

In September 1731, Cornelius Ford, Johnson’s greatest mentor, suddenly died. Three months later, just after he had managed to garner a loan to save his failing bookshop, Johnson’s father was hit with a fever and died as well. It was December 1731, and Johnson was forced to reckon with the fact that his two main anchors in life were gone.

He managed to get a job teaching at Market Bosworth grammar school near Lichfield, but he only lasted a few months. He later told a friend that leaving the position was akin to escaping prison.

1732 brought two notable events in Johnson’s life: He began his first major literary work, a translation of Portuguese Jesuit Father Jerome Lobo’s account of his travels to Abyssinia, and he met his future wife.

Johnson married the wealthy 45-year-old widow, Elizabeth Porter, when he was just 25 years old. And after a failed attempt to start a school in the country, he moved to London in 1737, leaving his wife behind until he could find his footing as a writer in the big city. In London, his literary career finally began to flourish.

Wikimedia CommonsSamuel Johnson married wealthy widow, 45-year-old Elizabeth Porter, when he was 25 years old.

His first major success came in May 1738 with the publication of London: A Poem in Imitation of the Third Satire of Juvenal — a 263-line satire that the greatest living English poet publicly lauded. Alexander Pope tried to locate the author, as London was published anonymously, and said “He will soon be déterré” (discovered).

After several more years producing publicly lauded works — including regular contributions to The Gentlemen’s Magazine — Johnson was commissioned to begin an eight-year effort to compile the most thorough and cohesive English-language dictionary the world had ever seen.

A Dictionary Of The English Language

For nearly two centuries, Samuel Johnson’s dictionary was the dictionary. Only when the Oxford English Dictionary was completed in the early 20th century did Johnson’s work take a backseat. But even still, it remains a remarkably impressive feat.

Samuel Johnson’s dictionary was one of the standards for 150 years, until the ‘Oxford English Dictionary’ arrived.

The project required six assistants, mainly to help copy the more than 114,000 literary quotations spread across 42,773 entries. It was more complex than any previous English-language dictionary; the comparable French Dictionnaire took 55 years to complete and required 40 scholars.

Nowadays, the dictionary is most famous for its humorous definitions — those that illustrate Johnson’s love of literature, illuminate his conservative political views, and highlight his exacting wit. The most cited, perhaps, is his definition of oats: “grain, which in England is generally given to horses, but in Scotland supports the people.”

In another colorful entry, he defined excise as “a hateful tax levied upon commodities and adjudged not by the common judges of property but wretches hired by those to whom excise is paid.”

But according to linguist David Crystal, these subtle jabs make up a tiny fraction of the dictionary’s definitions. “Although judgmental nuances are scattered throughout,” Crystal wrote in 2018, “I estimate that there are less than 20 really idiosyncratic definitions in the whole work – out of 42,773 entries…and 140,871 definitions.”

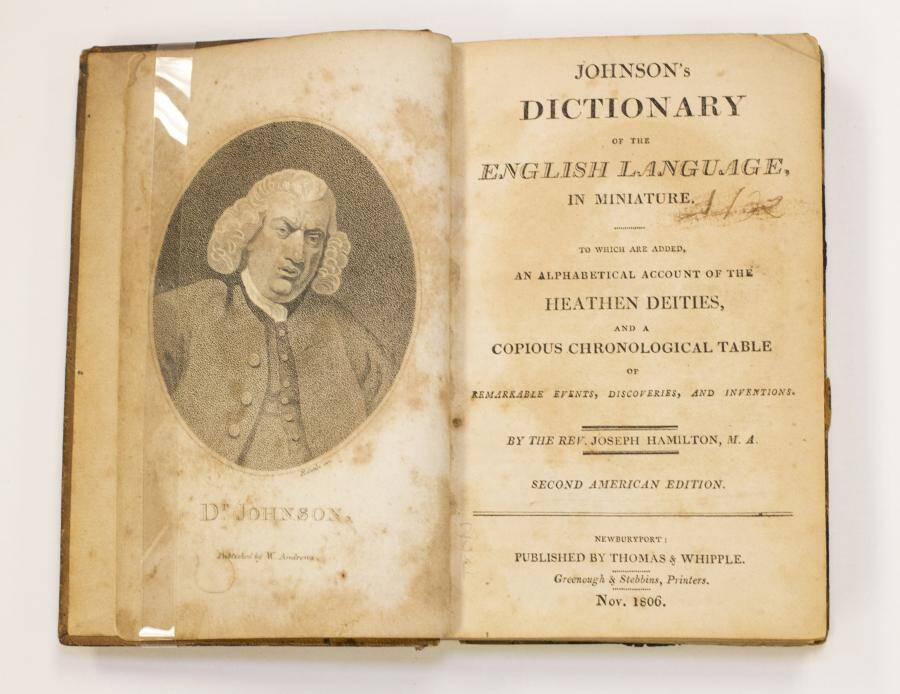

University of North TexasSamuel Johnson’s Dictionary of the English Language was a seminal work by a complicated — and colorful — figure.

So for every dig at the Scots, there are about 7,000 definitions that are painstaking in their attention to detail and nuance, while still boasting Johnson’s colorful way with words. The entry for take, for instance, included 134 uses and covered 11 columns of print, while the definitions of some more run-of-the-mill words became surprisingly entertaining.

For example:

Dull, adjective: Not exhilarating; not delightful: as, to make dictionaries is dull work.

Fart, noun: Wind from behind.

Love is the fart

Of every heart;

It pains a man when ’tis kept close;

And others doth offend, when ’tis let looseSock, noun: Something put between the foot and shoe.

Tarantula, noun: An insect whose bite is only cured by musick.

He also included obscure bordering on nonsense words, no doubt discovered in the myriad books he’d read over some four decades, such as:

Anatiferous, adjective: Producing ducks.

Cynanthropy, noun: A species of madness in which men have the qualities of dogs.

Hotcockles, noun: A play [game] in which one covers his eyes, and guesses who strikes him.

Jiggumbob, noun: A trinket; a knick-knack; a slight contrivance in machinery.

He rifled all his pokes and fobs

Of gimcracks, whims, and jiggumbobs. Hudibras, p. iii.Trolmydames, noun: Of this word I know not the meaning.

There are more than 114,000 literary quotations in the dictionary, many of which belonged to Johnson’s idol, William Shakespeare (10 years after his dictionary was published, he produced annotated versions of Shakespeare’s plays). Thus the dictionary was as much a testament to Johnson’s humor, wit, and perceptiveness as much as it was an authoritative guide to the English language.

Johnson’s Later Years: Love And Masochism

Samuel Johnson’s dictionary cemented him as an established, revered, and recognizable writer — and earned him a pension from the Whig government for the rest of his days.

And so from then on he wrote only what truly interested him, in contrast with the scrounging he had to do previously as a working writer. In 1765, he published his Shakespeare compendium, and in his 70s he wrote short biographies of 52 English poets, still celebrated today as a major work.

He spent much of his time dining with members of his “Club,” which included artists and thinkers he admired (like the writer Oliver Goldsmith and the painter Joshua Reynolds) and people who needed his help (a former prostitute, a blind poetess, and a former Jamaican slave whom he’d designate his heir).

In 1765, he was adopted, in a sense, by Henry and Hester Thrale, who at a dinner party were so taken by Johnson’s way with words that they gave him a rent-free room in their own home. Henry had inherited a successful brewery from his father and was a Member of Parliament, and Hester kept a series of diaries that serve as some of the most authoritative first-hand accounts of Johnson’s life.

Wikimedia CommonsA portrait of Hester Thrale and her daughter, Hester, by Joshua Reynolds. Circa 1777.

Hester and Johnson became very close; Johnson apparently loved her while maintaining a respectful relationship with her cold, philandering husband. Another of his close companions in his later years was James Boswell, an aspiring writer who would go on to write Johnson’s seminal biography, The Life of Samuel Johnson.

Both Thrale and Boswell were more than 30 years younger than Johnson, but they nevertheless formed a close, complicated triangle of friendship and admiration. In one excerpt of Boswell’s Life, Thrale moves close to Boswell and whispers, “There are many who admire and respect Mr. Johnson; but you and I LOVE him.”

From letters, diary entries, and other writings, we’ve learned that Johnson was, interestingly enough, a masochist, and that Thrale was perhaps the only person privy to his sexual urges. In two letters he wrote to Thrale in French (which at the time was considered the most erotic language), Johnson calls Thrale “Mistress,” and begs her to “keep me in that form of slavery which you know so well how to make blissful.”

In Thrale’s Anecdotes of the Late Samuel Johnson, published two years after his death, she wrote, “Says Johnson a Woman has such power between the Ages of twenty five and forty five, that She may tye a Man to a post and whip him if She will.” She added a footnote: “This he knew of him self was literally and strictly true.”

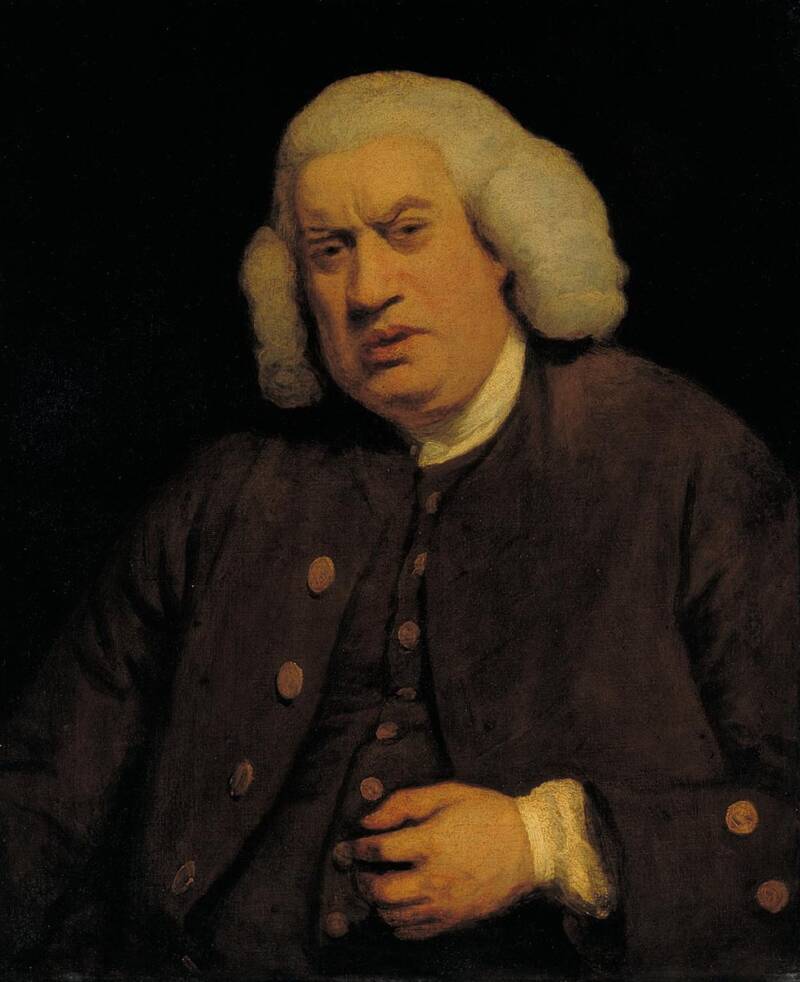

Wikimedia CommonsSamuel Johnson in his later years, as portrayed by John Opie. Date unknown.

He also gave her a padlock, which while some have construed as yet another sign of his kinkiness, may have actually been borne of his concern for his mental stability; if he were to go insane, he wanted his most trusted companion to lock him up before he could hurt anyone.

When Henry Thrale died in 1781 after a series of strokes, Johnson — and the people of England, who had long read of Johnson’s and Hester’s relationship in the tabloids — assumed Hester would want to marry Johnson. But instead, to everyone’s utter shock, she wed her child’s music teacher, a lower-class Italian named Gabriel Mario Piozzi.

The loss killed Johnson. On Dec. 13, 1784, just five months after Thrale’s and Piozzi’s wedding, he died and was buried in Westminster Abbey.

Tourette’s, masochism, blind poetesses — there’s a lot to unpack in the 75-year span of one of history’s greatest writers. He was a man born with little money who became a celebrated wordsmith in his own lifetime, a man who defined more than 42,000 words in 2,500 pages, all before the invention of computers, the internet, or even index cards.

Samuel Johnson climbed a proverbial mountain that nobody had ever summited before. For more than 150 years, his work was the ultimate reference. And three centuries on, it remains a remarkable feat.

After learning about Samuel Johnson and his dictionary, explore the interesting origins of seven common English idioms. Then, discover who actually wrote the Bible.