SeaWorld's first Shamu was captured in 1965 and forced to perform at their San Diego park for six years before she died prematurely in the wake of cruel and abusive treatment.

LS Photos/AlamyThe first Shamu was captured and taken to SeaWorld in 1965, but the name was later trademarked and used for all of the company’s orcas.

Shamu is a name known across the world, solely due to SeaWorld. For decades, the company has advertised its killer whale shows as spectacles made for the whole family to enjoy. But behind the scenes, this allegedly family-friendly entertainment has been reported to be inhumanely cruel — and deadly.

The most infamous and enlightening example of the negative effects of SeaWorld’s treatment of its orcas was, of course, Tilikum, the killer whale at the heart of the documentary Blackfish. But while Tilikum’s story reached a massive audience, it was hardly an isolated incident.

“Shamu” has long been used as a moniker for nearly every orca kept at SeaWorld — a brand name, if you will.

But that name derived from the very first healthy orca intentionally captured and used in SeaWorld’s performances. And her story, like that of many other orcas held in captivity, is most certainly a tragedy.

The First Shamu And The Legacy Of Cruelty That Followed

In 1965, a three-year-old female orca was captured in the wild after whalers harpooned and killed her mother. The young orca had refused to leave her mother’s body, so the whalers dragged her away from her mother’s corpse. They then sold her to SeaWorld San Diego.

This young orca, now known as Shamu, was trained to be SeaWorld’s first performing killer whale. She was confined to a small tank, and in order to teach her tricks, trainers often deprived Shamu of food.

P. Maguire/AlamyA Shamu performance at SeaWorld Orlando.

For several years in the late 1960s, Shamu was featured prominently in SeaWorld’s live shows, but in 1971, a harrowing incident would put an end to Shamu’s performances.

During a televised publicity stunt, SeaWorld PR secretary Annette Eckis was instructed to perform with Shamu and ride on the young orca’s back. With the cameras rolling, Eckis slipped off of Shamu’s back and into the water. The killer whale quickly turned on Eckis, biting down on her leg and refusing to let go.

Eventually, a trainer got Shamu to release Eckis by shoving a pole into the killer whale’s mouth and prying it open. Eckis required more than 100 stitches and sued SeaWorld after the incident. Shamu was retired from the park’s performances.

Later that year, Shamu died of a combination of pyometra (a uterine infection) and septicemia (blood poisoning). She was nine years old. On average, wild female orcas live to be 46. Many live to be much older, reaching 80 or 90 years of age.

But Shamu’s death hardly marked the end of SeaWorld’s orca shows. By this point, Shamu had become a brand — one that was incredibly profitable and valuable to the company. They continued to capitalize on this brand, bringing in a host of other performing orcas, each given its own name but billed as a part of the park’s “Shamu Shows.”

SeaWorld’s Treatment Of Captive Orcas

SeaWorld trademarked the name “Shamu,” and as it began to open more parks across the world, each one received its own “Shamu,” which was just the moniker given to any number of interchangeable captive orcas.

Like the original Shamu, these orcas were confined to small areas that, compared to the vastness of the open ocean, were no bigger than a bathtub to them.

According to animal rights activist Ric O’Barry, the former animal trainer who was recognized in the 1960s for capturing the dolphins used in the TV series Flipper, the harsh treatment of SeaWorld’s orcas didn’t stop there. Trainers controlled and bribed captive orcas to “shape” their behaviors, replacing their natural instincts with a series of abnormal behaviors to entertain paying audiences.

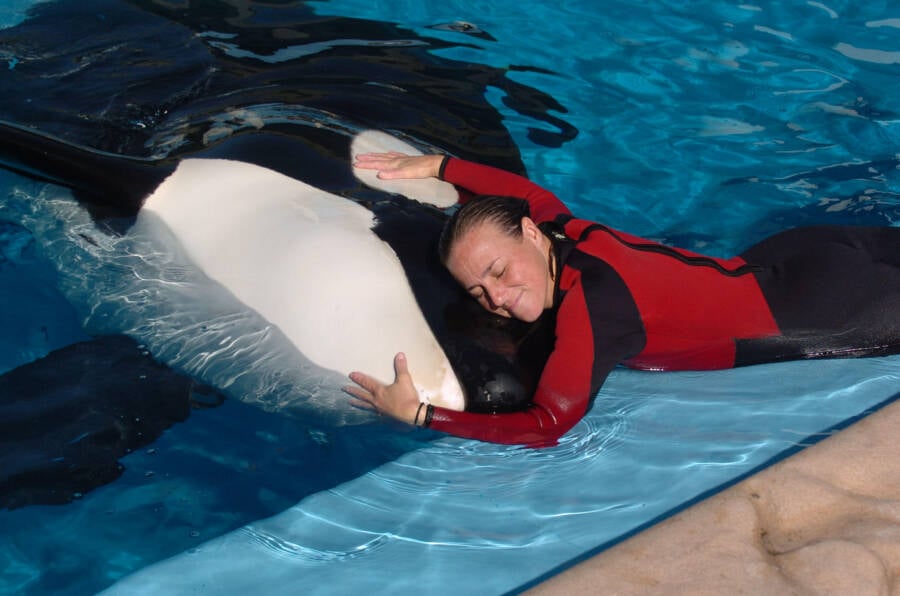

Peter Titmuss/AlamyA trainer at SeaWorld Orlando riding one of the park’s orcas during a performance.

In nature, orcas can swim up to 100 miles a day and dive several hundred feet deep, spending much of their time foraging, socializing, and navigating the vast ocean environment that surrounds them.

In captivity, they were reshaped into pets that relied on their trainers for food and attention and often had to beg for it. They were forced to abandon their natural instincts and instead perform a series of behaviors that must have seemed entirely odd to them, such as beaching themselves on platforms, waving to a cheering crowd, and letting trainers ride on their backs in exchange for dead fish.

Their tanks did not even closely resemble their natural ocean environments. Rather, they allegedly spent much of their time in sterile concrete rooms, swimming circles in minuscule tanks until they were asked to perform.

But it wasn’t enough that SeaWorld was taking orcas from their natural environment and transporting them to their parks; they were also breeding their captive orcas, then using the offspring in shows as well, often separating the young orcas from their parents and sending them to various parks across the country.

The most infamous example of this practice came in 1985, when SeaWorld introduced “Baby Shamu” at its park in Orlando, Florida. Baby Shamu’s actual name was Kalina, and she was the first orca to live after being born in captivity.

The Tragic Life Of ‘Baby Shamu’

Because SeaWorld was not required to report the number of orca deaths at its parks until 1994, the actual number of orcas who died at its parks prior is difficult to ascertain. That said, some estimates suggest that at least 10 captive-bred baby orcas were born before Kalina — all of whom were either stillborn or died within two months.

Paul Broadbent/AlamyA Shamu blimp advertising SeaWorld Orlando.

Kalina became an immensely popular attraction for SeaWorld Orlando — so much so that when she was four years old, the company took her away from her mother and sent her to SeaWorld Ohio to boost its ticket sales. Less than a year later, they transferred her once again, this time to SeaWorld San Diego, then SeaWorld San Antonio eight months after that.

When Kalina was just six years old, she was impregnated so that SeaWorld could have yet another Baby Shamu.

In the wild, the average age of reproduction for orcas is 15. Shortly after the birth of her first calf, Kalina was impregnated again. In total, she gave birth to four calves. Three of them survived and were taken away from her, shipped all over the country. The other was stillborn.

Kalina died in 2010 of septicemia. She was only 25 years old.

Tilikum, SeaWorld’s Most Infamous Killer Whale

Julie Fletcher/Orlando Sentinel/TNS/Alamy Live NewsSeaWorld trainer Dawn Brancheau, who died in 2010 after the orca Tilikum attacked her and dragged her beneath the water.

Of course, the most notorious of SeaWorld’s killer whales was the subject of the 2013 documentary Blackfish, which put the conditions SeaWorld imposed on its orcas front and center for the world to see. The orca’s name was Tilikum, and over the course of his time at SeaWorld, he killed three people, two of whom were his trainers.

Tilikum had been under immense stress. Held in captivity, he deteriorated both mentally and physically as he was kept in a cramped tank and regularly physically abused by the other orcas. He was bred 21 times; 11 of his calves died before he did.

He was not the only orca to be treated this way. And while Tilikum’s life was tragic, his story ended up serving a larger purpose: to highlight the inhumane treatment captive orcas are often subjected to.

SeaWorld, in the wake of this widespread controversy, eventually agreed to stop breeding orcas and put an end to the “Shamu” name, with the president of SeaWorld San Antonio, Carl Lum, saying the park would seek to focus on a “Shamu-free future.”

Nearly 60 years after the capture of the first Shamu, that name has become tarnished by the decades of cruel treatment that followed. Now, it looks as though both the name and the notorious shows associated with it will be retired.

After reading about the dark, true story of Shamu, learn more about Dawn Brancheau, the SeaWorld trainer killed by Tilikum. Or, read about the orcas who have been attacking boats off the European coast.