Elasmotherium sibiricum was a massive rhinoceros that once lived in the grasslands of Eurasia and could grow to the size of an elephant.

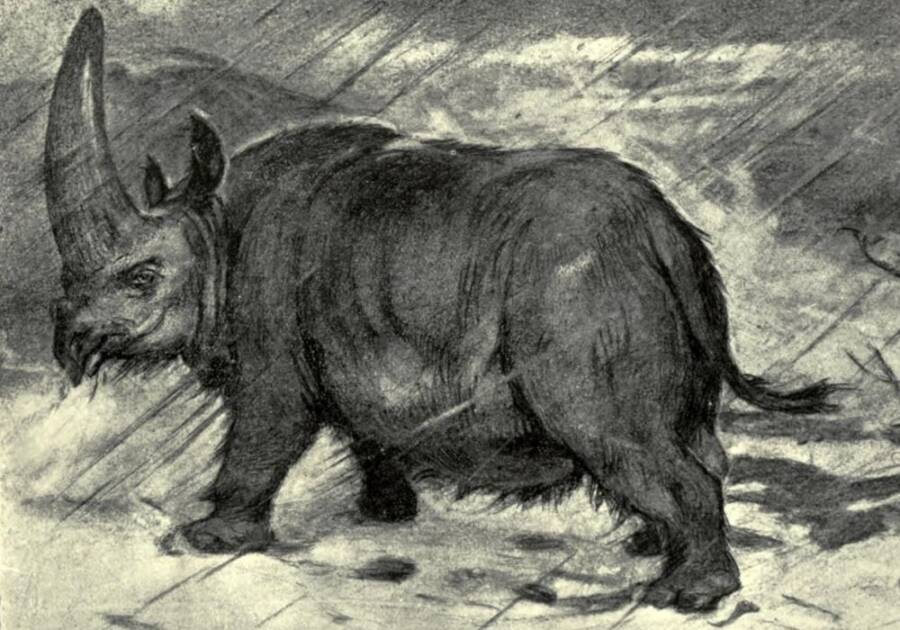

Public DomainA 1912 drawing of the Siberian unicorn, which was believed to have a three-foot-long horn that protruded from its head.

Millions of years ago, a massive, shaggy rhinoceros known as Elasmotherium sibiricum roamed the grasslands of Eurasia. Today, scientists believe the prehistoric giant sported a single long horn on its head, a feature that gave the creature its modern nickname: the Siberian unicorn.

While there are just five types of rhinos on Earth today, up to 250 different species existed in the past. E. sibiricum was one of the most impressive. The beasts were twice as heavy as modern rhinos, weighing in at nearly 10,000 pounds.

Scientists once believed Siberian unicorns went extinct more than 100,000 years ago, but recent research has turned this theory on its head. Now, there is evidence that E. sibiricum was still alive 39,000 years ago, meaning the creatures lived alongside both Neanderthals and modern humans.

So, what happened to these extraordinary animals? Unlike some of the other megafauna they co-existed with, Elasmotherium sibiricum probably wasn’t hunted to extinction. Instead, the changing climate during the last Ice Age caused the rhinos’ grassland habitat to shrink, leading to the gradual reduction of their population over time. Although Siberian unicorns vanished from the Earth, though, the fossils they left behind may have sparked myths about some of the most iconic fairytale creatures.

What Was The Siberian Unicorn?

Around 43 million years ago, the Elasmotheriinae subfamily split from the Rhinocerotidae family, which includes modern rhinoceroses. Elasmotherium sibiricum emerged as a species of this new group, making it further separated from today’s rhinos than humans are from monkeys.

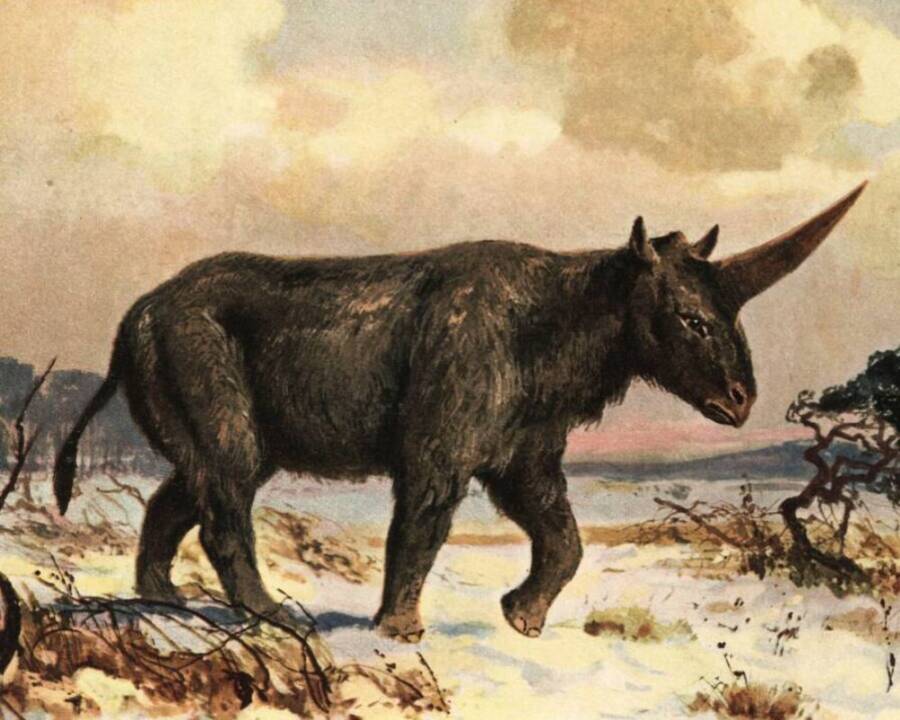

Public DomainThe Siberian unicorn was nearly the size of an elephant and was likely covered in shaggy fur.

During the last Ice Age, E. sibiricum lived in the grasslands that stretched from Ukraine to Kazakhstan to Siberia alongside other animals like woolly mammoths, cave lions, and antelope. Despite their massive size — 15 feet long, eight feet high at the shoulder, and nearly 10,000 pounds — the creatures were likely able to speed across the Eurasian steppe to avoid predators when necessary.

Siberian unicorns also sustained themselves almost entirely on dry grass, as evidenced by their flat molars and lack of front teeth. So, when their habitat started shrinking as the climate changed during the last Ice Age, they were particularly susceptible to drastic population decline.

A paleontologist named Gotthelf Fischer von Waldheim first described E. sibiricum in the early 19th century. A jawbone with teeth still inside had been gifted to Moscow University by Princess Yekaterina Dashkova, and the scientist named the new species Elasmotherium from the ancient Greek word elasmos for “laminated” and therion for “beast,” a reference to the creature’s tooth enamel. Sibiricum was a nod to the fact that most of Dashkova’s fossil collection came from Siberia.

Public DomainThe first published drawing of Elasmotherium sibiricum (1878).

Some 60 years later, another naturalist determined that the Siberian unicorn was in a separate family from modern rhinos, though some scientists disagree. In the centuries since, many other E. sibiricum specimens have been uncovered, allowing researchers to learn more about the prehistoric creature. Still, until recently, one major question remained: When exactly did the Siberian unicorn go extinct?

Inside The Downfall Of ‘Elasmotherium Sibiricum’

Scientists initially estimated that the Siberian unicorn died out between 100,000 and 200,000 years ago, but a 2018 study published in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution challenged that theory. Researchers radiocarbon dated 23 specimens and found that they were much younger than they’d expected. In fact, the creatures may have existed in eastern Europe and central Asia until as recently as 35,000 to 39,000 years ago.

Igor Doronin/Kosintsev et al./The Natural History Museum of LondonThis display at the Stavropol Museum in Russia is based on a nearly complete skeleton of E. sibiricum found nearby in 1964.

E. sibiricum was the last surviving member of the Elasmotherium family. The group also included E. primigenium, the oldest species in the family; E. chaprovicum, another early member of the family discovered in the Caucasus region; E. peii; and E. caucasicum, which may have been even larger than the Siberian unicorn.

When E. sibiricum went extinct, the entire group died out with it. Only the similar Rhinocerotidae family lived on, eventually giving birth to the rhinoceros species that roam the Earth today.

The authors of the 2018 study wrote a piece for The Conversation further explaining the demise of the Siberian unicorn. “Climate change seems a likely contender,” they noted, “but 36,000 years is well before the height of the Ice Age, which occurred 20,000 to 25,000 years ago.”

“But this date does match the timing of a pronounced change towards cooler summers across Northern Europe and Asia,” the authors continued. “This seasonal change resulted in grasses and herbs becoming more sparse, and an increase in tundra plant species such as mosses and lichens.”

However, this change didn’t lead to the demise of some of the other creatures the Siberian unicorn lived alongside, such as the saiga antelope, which still exists today. The scientists wondered why this was, so they compared the nitrogen and carbon in the bones of E. sibiricum and saiga antelopes from around the same time period. They found that 36,000 years ago, saiga started eating different types of plants — not just the dry grass that Siberian unicorns ate.

Andrey Giljov/Wikimedia CommonsThe saiga antelope, which lived alongside the Siberian unicorn, can still be found in central Asia today.

“But shifting from a grass diet proved too difficult for the Siberian unicorn, with its special folded wear-resistant teeth and a low-slung head right at grass height,” the researchers wrote.

So, the Siberian unicorn’s inability to adapt ultimately led to its downfall. However, the species’ legacy continues both through the fossils it left behind and the iconic myths it may have contributed to.

Did ‘E. Sibiricum’ Fossils Lead To The Legend Of The Unicorn?

Unicorns were first depicted around 2600 B.C.E. on stone seals in the Indus Valley. However, the earliest written descriptions of the mythical beasts come from ancient Greece more than 2,000 years later.

In his book Indika, the writer Ctesias wrote, “There are wild asses in India the size of horses and even bigger. They have a white body, crimson head, and deep blue eyes. They have a horn in the middle of their brow one and a half cubits [over two feet] in length. The bottom part of the horn… is bright white. The tip of the horn is sharp and crimson in color while the rest in the middle is black.”

The Roman author and naturalist Pliny the Elder wrote of the monokeros, an animal that had the head of a stag, feet of an elephant, tail of a boar, and body of a horse. His version of the unicorn also had a long horn in the middle of its forehead. Even Marco Polo wrote of the extraordinary creatures.

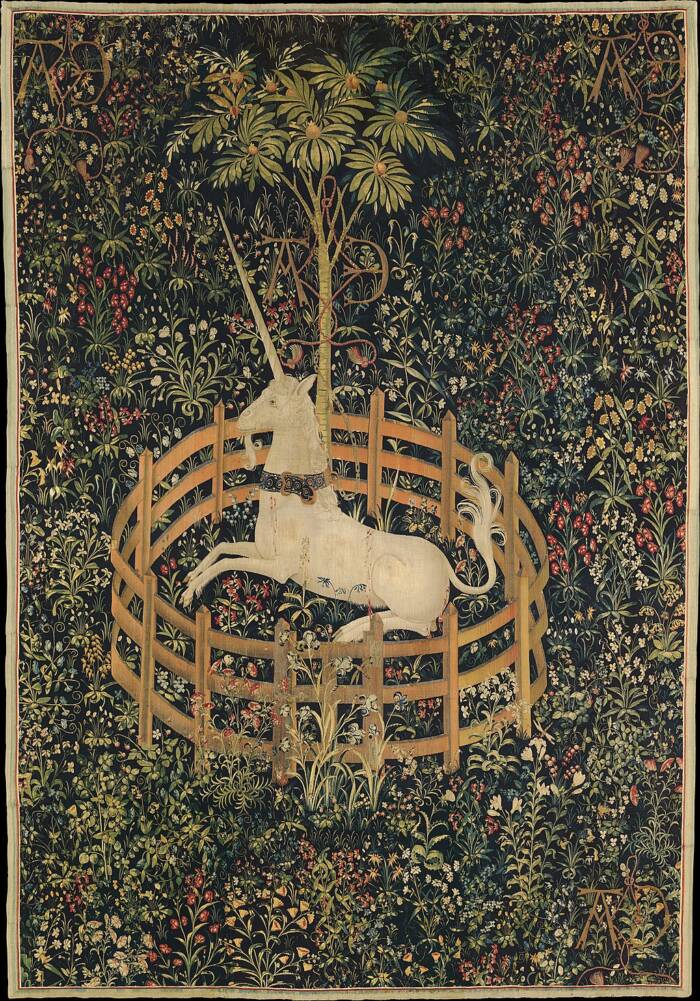

Public DomainOne of history’s most famous unicorn depictions dates to c. 1500.

By the Middle Ages, unicorns were commonly featured in fairy tales and myths across the globe. So, why did so many cultures tell stories about unicorns if they didn’t actually exist? And what do these tales have to do with E. sibiricum?

It’s likely that ancient people came across horns from other animals, such as rhinos and narwhals, and crafted fables of unicorns around them. Someone who happened upon a three-foot-long horn of a Siberian unicorn thousands of years ago may have easily mistaken it for that of a real unicorn.

There’s just one issue: No horn from E. sibiricum has ever been found. While there is evidence from fossilized skulls that the appendage existed, there is no concrete proof about what it looked like. For now, the only confirmed connection between the Siberian unicorn and the unicorns of fairy tales is their name.

After learning about the Siberian unicorn, discover when woolly mammoths went extinct. Then, go inside the legend of the jackalope, the mythical horned rabbit of the American West.