Movies are as much about moving images as they are sound—which is why Foley artists are so important.

Student working on the Foley room of the Vancouver Film School.

While director Stanley Kubrick was filming Spartacus, he went to Europe to record combat scenes. He chose to shoot in Spain, and there, just outside of Madrid, he filmed his armies of Romans marching across the country’s flat, dry plains.

Thousands of Spanish soldiers paraded in Kubrick’s Roman army, but when the sound arrived back in the U.S., it was in such bad condition that it was unusable. With a production price tag already hovering in the tens of millions, going back to Europe and filming it all over again would have been a very expensive remedy.

The solution to Kubrick’s dilemma came from a man named Jack Foley, a New Yorker who had moved to California and worked for Universal Studios. Upon hearing Kubrick consider the idea of reshooting the march, Foley is claimed to have run to his car, fetched a big set of keys and jangled them in front of a microphone to recreate the sound of the army’s metallic armor jostling during a march. It worked — very well, in fact — and the movie was released in 1960.

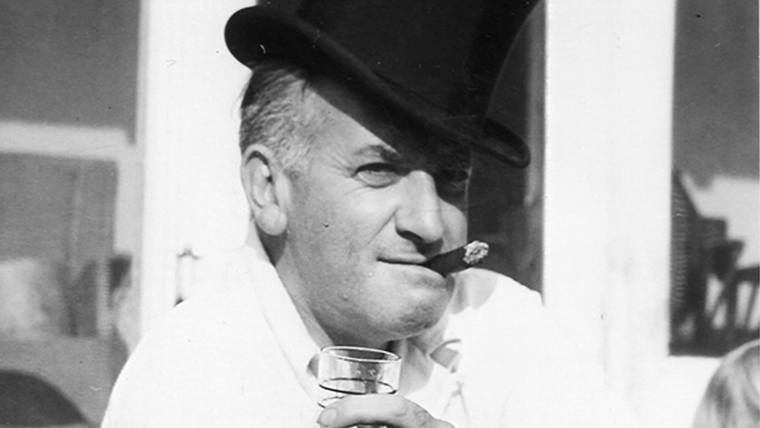

Jack Foley, the eponymous “Foley Artist.” Image Source: Clockwork Brothers

By the time Foley saved Spartacus, he had already been working with sounds for decades. For Operation Petticoat, a 1959 film, he recorded his own belch and played it backwards to imitate the sound of a submarine. Foley’s innovative work marked the beginning of an art that, when done right, goes unnoticed. It also marked the formal emergence of a new creative cadre: the Foley artists.

A student matches his steps to those on screen in the Foley room of the Vancouver Film School.

Sound artists had existed since the early 20th century, but since the 1960s, Foley artists have worked to recreate two types of sound. First, they add the sound that is not recorded when filming, such as the sound too soft to be heard or that accompanies movies when dubbing.

They also create the sound that is not made by anything but that the audience needs for cinematic effect. For instance, Foley artists made the footsteps of E.T. more believable, the moving sounds of R2D2 more entertaining, and the flapping of birdwings in Hitchcock’s classic The Birds more terrifying.

Traditionally, when giving a film the Foley process, it’s critical that the sound is recorded on set and that the artists work while watching the movie – but these requirements are changing with the development of advanced recording technology.

“Foley is important because the sound that these artists create is live recorded, synchronizing movements and actions. It is also important because the artists recreate emotions in each action that they do,” says Gustavo Bernal, video editor and post instructor at Havas Worldwide, an advertising agency in New York.

“I am fascinated by the fact that a broken bone is recreated with rigatoni pasta, celery or broccoli, or that a pumpkin can be used to recreate the sound of a broken skulls or that chamois cloth is used to create blood or viscous sounds,” added Bernal.

A room full of Foley props.

But not everything is an ongoing play-date for Foley artists. As digitalization extends its reach to all aspects of life, Foley art is in danger. Today, anyone can record herself and send a voice note. The most basic computer editing programs already carry a broad selection of thumps and zings and whirs, which means that the Foley process is more time consuming and expensive by comparison.

After a century of Foley artists using their imaginations to make footsteps, gushes of blood, and kisses feel real and close to viewers, could it be that the next and final sound for Foley artists to emulate is the silence of the grave?

Car doors and other metallic pieces used as props by Foley artists. Image Source: Flickr

Bernal, who is also the co-producer and editor of Actors of Sound, an upcoming documentary about sound effect artists, offers a defense of the Foley artists’ craft and the necessity of human-produced sound in film. Says Bernal, “Human actions are not perfect or constant. There are variations in them, especially in things such as footsteps or the movements of fabric and clothes.”

Foley artist Caoimhe Doyle expresses it very well when she says, “The pictures might tell us what’s happening in the film, but the sound tells us how to feel about what we are seeing.”

Only a human, it would seem, can comprehend and emulate these very human irregularities, and channel their sound into art that compels the audience to respond.