An analysis of seven 2,500-year-old skulls uncovered at the Iron Age settlements of Ullastret and Puig Castellar in northern Spain revealed that the majority of them belonged to people who weren't local to the area, suggesting they may have been prisoners of war.

Carquinyol/Flickr The ruins of Puig Castellar, the Iron Age settlement in Barcelona where researchers found human skulls from prisoners of war.

For more than a century, archaeologists have been finding decapitated human skulls at Iron Age sites in Spain. Many of these skulls were once nailed to walls in both public areas and domestic settings, leaving researchers baffled about their purpose. Were they gruesome trophies of war or relics meant to honor important members of society?

Recently, a team of scientists set out to answer this question by analyzing skulls from the Iron Age settlements of Puig Castellar and Ullastret. Their findings suggest that both possibilities may be true, offering a fascinating glimpse into the mysterious social fabric of ancient Iberia.

Examining The Ancient Decapitated Skulls In Catalonia

In the sixth century B.C.E., Iberian societies began interacting more with other Mediterranean civilizations, leading to the establishment of new settlements along trade routes — and increased violence with outsiders.

Two of these settlements, Puig Castellar in Barcelona and Ullastret in Girona, have since revealed a macabre truth about the Iron Age people who lived there: They often nailed severed heads to walls for public display.

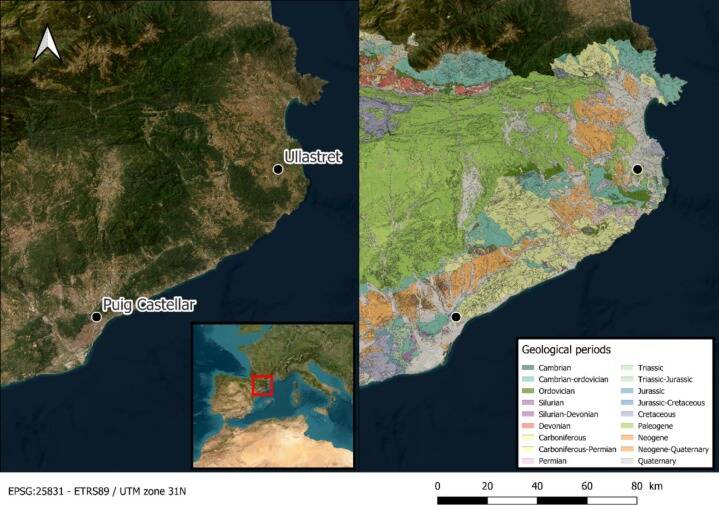

Rubén de la Fuente-Seoane et. al./Journal of Archaeological ScienceMaps of Ullastret and Puig Castellar.

Many scientists initially theorized that these skulls had belonged to respected community members and were put on display for veneration purposes. However, a recent study published in the Journal of Archaeological Science found that may not have always been the case.

Researchers recently took a closer look at seven skulls from Puig Castellar and Ullastret in an effort to find out more about the severed heads. They discovered that four of the skulls had belonged to people who did not live locally, suggesting they were war prisoners or defeated enemies — and their heads were displayed as a show of power, not respect.

Why Did Ancient Iberians Display Skulls?

To analyze the skulls from Puig Castellar and Ullastret, scientists conducted bioarchaeological analysis to determine their geographical origins. They also compared their findings with the isotopes of local plants and animals.

Of the four skulls from Puig Castellar that were studied, only one was from a local, while the other three belonged to foreigners. Because these severed heads were found in high-traffic areas, the research team theorized they belonged to enemies.

patrimoni.gencat/FlickrAn aerial view of Puig Castellar.

“The individuals from Puig Castellar were all found in an area of great public exhibition, such as the settlement’s entrance gate,” the study’s authors wrote. “We do not know if they were nailed to the wall or in some other area of the entrance, although the assumption that they were placed in the wall has led to interpreting these skulls as trophies of war.”

Scientists also studied three skulls from Ullastret, determining that two of them belonged to locals. Both of these decapitated heads were unearthed in domestic structures, such as homes or private quarters. Because of this, the team believes they were from important community members rather than war prisoners.

“The exposed remains would be important inhabitants of the settlement,” the researchers wrote, “possibly venerated or vindicated by society, perhaps associated with family groups or rival factions vying for power. In addition, the contexts in which these remains were found are interpreted as domestic units or dwellings.”

AlbertRA/Wikimedia CommonsSkulls from Puig Castellar dating back to 300 B.C.E.

The third Ullastret skull was also linked to a foreigner. It was found in a burial pit, which “could align with the hypothesis that the heads of ‘enemies’ were brought as a trophy, and stored in boxes or pits, a practice documented among the Gauls of southern France.”

Lastly, the research team found that the decapitated prisoners of war were not chosen randomly: “These severed heads reveal a homogeneous trend in terms of sex, as all are male; however, the mobility and depositional patterns suggest greater diversity, implying social or cultural differences among individuals from these two Iron Age communities.”

These findings offer fascinating insights into warfare, violence, and trade in pre-Roman Iberian societies — cultures that remain largely shrouded in mystery.

After reading about the new analysis of Iron Age skulls found in Spain, dive into 44 disturbing photos of life as a prisoner inside a Soviet gulag. Then, view 30 harrowing images of prisoners of war throughout history.