When the SS Dumaru was struck by lightning and sank near Guam in 1918, its crew was left adrift in a lifeboat for three weeks — and when food ran out, they turned to cannibalism.

Wikimedia CommonsThe SS Dumaru sets off on its fateful maiden voyage.

In 1918, a wooden ship called the SS Dumaru set off on its maiden voyage. Tragically, that first trip would be its last: On October 16, the ship was struck by lightning, setting its flammable cargo ablaze and sending its crew members out to sea in three separate life vessels. But the sailors’ troubles were only beginning.

While one life raft carrying five Dumaru survivors made it to safety after only nine days, the other two lifeboats were adrift for over three weeks. For one of these vessels, which was overwhelmingly above capacity, the situation soon grew dire as their meager food and water supplies dwindled. By the time they were rescued, only 14 of the original 32 men aboard this craft were left.

After their return to land, the remaining sailors agreed to keep one crucial bit out of their survival story to themselves. It was many years before one of them finally revealed how those 14 really survived: After the men ran out of food, they had resorted to cannibalism, eating the corpses of some of the men who died of exposure.

This is the story of the sinking of the SS Dumaru and the grisly survival story that followed.

What Was The SS Dumaru?

The SS Dumaru was a 1752-ton wooden U.S. steamer, as described in a 1918 Sunday Oregonian article.

It was a 270-foot Hough-type vessel, and according to the Connecticut Examiner, poorly built. In fact, when it launched in Portland on April 17, 1918, it tumbled too quickly into the water and smashed into several houseboats on the Willamette River — which some seamen took as an omen of impending disaster.

Still, the vessel set out on its maiden voyage that year. Captained by Ole Berrensen, it departed San Francisco in September 1918, stopped in Hawaii, and sailed to Guam.

Notably, the vessel was made primarily of wood, and its cargo included a hoard of gasoline in the ship’s forward, and a stash of dynamite and other munitions in the after-hold — all highly flammable materials that would make for an explosive maiden voyage.

On Oct. 16, the Dumaru left Guam’s Apra Harbor and headed for Manila. It was on this last leg of the trip that disaster quite literally struck.

Public DomainAn aerial view of the U.S. Navy base in Guam’s Apra Harbor in 2006, only about 20 miles away from where the Dumaru sank.

The Sinking Of The SS Dumaru

As the ship pulled away from Guam that fateful day, heavy stormclouds were already gathering overhead. Before long, the storm broke — and when the ship was only about 20 miles from Guam’s coast, lightning stuck the wooden deck of the ship, setting off a chain reaction as the ship’s highly flammable cargo lit up and exploded. In a 1919 issue of Popular Science, one of the survivors, Theron W. Bean, wrote that the entire forward of the ship caught fire in seconds as the lightning ignited the gasoline inside.

The call went out to abandon ship. Bean wrote that he sent out a distress signal as the men rushed to board the ship’s three life vessels: a small life raft and two lifeboats.

In their panic, the men did not evenly distribute themselves between the boats. One of the two lifeboats departed with only nine people filling its 20 seats. The other, which Bean had the misfortune of joining, was overstuffed. By the time he had finished sending the distress signal, jumped overboard, and swam to the boat, there were already 31 men aboard.

At this point, the three life vessels got separated. Each would make its own journey back to land.

On Oct. 26, the Sunday Oregonian reported that Captain Berrensen, his second mate, and three crew members were found safe in their life raft and picked up by a transport just nine days after the ship sank. The other lifeboats were still missing — and would spend another two weeks at sea. Each of the nine men on the understaffed boat would make it safely to shore.

The boat of 32 wasn’t so lucky.

The Harrowing Journey Of The Overstuffed Lifeboat

In his essay, Bean shares a gripping tale of survival as the 32 men on his lifeboat struggled to stay alive at sea.

After their boat landed in the water, he writes, the men watched from a distance as the Dumaru collapsed into the sea. They rowed away — and kept rowing. By morning, Guam was in sight. But a change of wind and strong currents tragically sent the lifeboat off course.

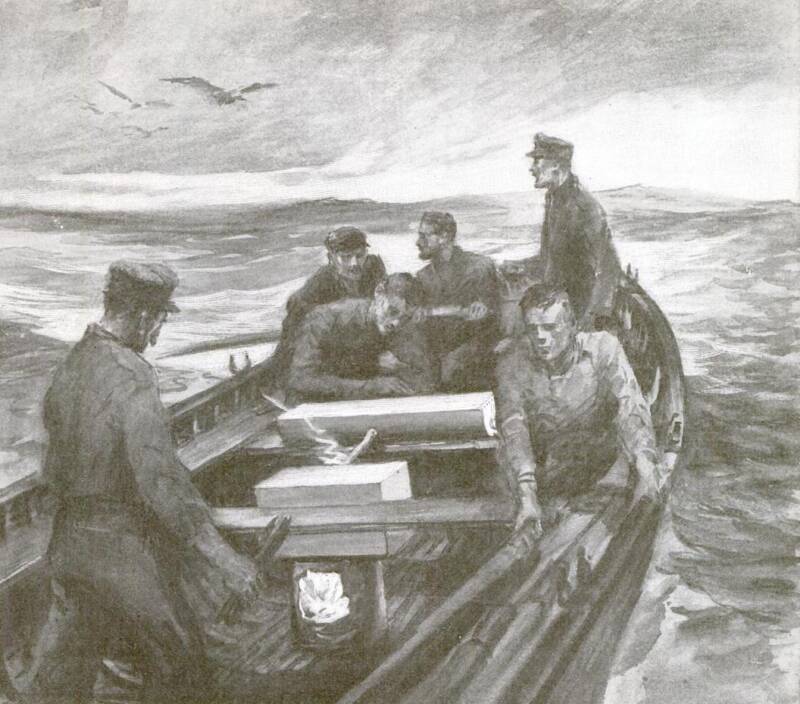

Public DomainAn illustration from Theron W. Bean’s essay on surviving the SS Dumaru sinking, which appeared in a 1919 issue of Popular Science.

Soon, hope arrived in the form of another steamer, passing in the distance. Frantically, the men started waving and shouting, trying to flag it down. It was to no avail. The boat maintained its course and passed right by them.

As the men waited and waited for the wind to change in their favor, or to see another ship, the situation grew dire. Their rations were low, and they were allotted only two tablespoons of water and one hardtack, or dense cracker, a day.

After a week, the men, in their weakened state, gave up rowing and were set adrift.

After about two weeks, the men started to die off rapidly of exposure, and on the 17th day, they finished their meager rations of hardtack. It still had not rained.

In their thirst, some men desperately tried to drink saltwater — and died soon after. Others tried to fashion an evaporator by using their shoes, oars, and the gunwales of the boat to fuel a fire, but even this gave the men only a swallow of water each.

Finally, Bean wrote that they managed to catch a couple of dolphins by using a bailing pump rod as a fishing tool. This meal, and the moisture they got from it, offered the starving men some momentary relief.

On the 24th day, the lifeboat finally neared land. For the first time in weeks, the men felt a sense of hope as the shores of the Philippines drew nearer — but first, they had to get through the rough surf and reach the beach.

Overcome by the choppy waves, the lifeboat capsized, throwing the men onto a coral reef, where they were cut up on the rough coral and tossed about by the heavy waves. Two more men died during this final struggle.

The men had traveled 1200 miles over open sea and arrived at last at the Philippines, where they were greeted and rescued. But for many of them, it was too late. The lifeboat had started with 32 men. Only 14 of them had survived.

What Bean doesn’t mention in his account is what purportedly happened to the bodies of the men who died at sea.

Years after the incident, a startling report would reveal that the starving men aboard the overstuffed Dumaru lifeboat had resorted to cannibalism, eating some of the bodies of the men who died of exposure.

Reports Of Cannibalism On The SS Dumaru Lifeboat

For years, the Dumaru survivors omitted mention of cannibalism when sharing their tale of survival. Then, in 1930, Lowell Thomas published a book the sinking of the SS Dumaru titled The Wreck of the Dumaru: A Story of Cannibalism.

According to the New York Times, the narrative that drives the book was relayed to Thomas by Fred Harmon, who had been an assistant engineer on the Dumaru and one of the 14 survivors from the overstuffed lifeboat.

The Times wrote that a version of this gruesome story, which Thomas obtained for his book, was also reported in Navy records from the Philippines from the time of the incident.

Public DomainA 1918 clipping from the Adelaide Chronicle detailing the arrival of the 14 Dumaru lifeboat survivors.

According to these records, four men died on the lifeboat on day 18. One of them, the first engineer, had previously told the men that when he died, they should eat his body.

So they did. They boiled the meat in a kerosene can. According to the report, “they said it tasted very good” as it had absorbed the salt from the water “and everyone seemed to feel better.” Worrying they’d get ptomaine poisoning from the salt, the men eventually put it aside. They ate more the next day, and this time, the salt “made everyone sick and crazy.”

But according to Fred Harmon’s recollection, the idea came from a mutinous Greek sailor named “George.”

Mutiny On The Lifeboat

Relaying Harmon’s version of the events, Thomas writes that “George,” a Greek sailor, led several hungry lifeboat passengers in a mutiny. Wielding a hatchet, he allegedly demanded that they eat those who had died of exposure. When some of the other men refused, George got angry, yelling, “We’re all dying. Cook the chief. I’m going to do it now.”

Allegedly, on the encouragement of the Dumaru‘s first mate, George did prepare the bodies for the men to eat after discussing with Lieutenant E.V. Holmes whether it was safe to do so.

“The lieutenant went ahead and ordered the Greek to place small parts of flesh on the wooden boat bailer that was shaped like a large sugar scoop, and then wash them in the sea,” Harmon said, according to Thomas. “Afterward, the wooden bailer was passed around to all.”

Harmon goes on to say that George ate first, then passed the bailer and “offered the flesh to Holmes, who took it and ate it, thereby showing the rest of us that he desired us to do likewise. We ourselves had come around to his [George’s] way of thinking. We decided to go right on with what the Greek started.”

Though the men had initially been horrified at the idea of eating their crewmates, they eventually agreed that it was “the only possible means of saving our lives, and for our comrades it was a fate not much worse than to be eaten by sharks.” After eating the head engineer, they allegedly also ate a Hawaiian mess boy.

The Connecticut Examiner reports that after this book was published in 1930, the survivors admitted to succumbing to cannibalism to survive.

This story was shocking enough. But the Examiner also reports that “speculation still persisted about several alleged suicides” — that some men jumped overboard and became shark food rather than risk being eaten by their comrades — “and grisly, unsubstantiated rumors of casting lots before an unlucky chief engineer and Hawaiian mess boy were killed, cooked and eaten.”

Tragically, had it not been for a shift in the wind, or had the passing steamer noticed the small lifeboat and come to its rescue, this gruesome and tragic tale could have been avoided.

After reading about how the SS Dumaru survivors resorted to cannibalism, read about another terrifying shipwreck that ended in cannibalism: the HMS Terror. Then, learn about the Donner Party and its shocking descent into mass cannibalism.